Autor : Rey, DarĂo R.1

1Consultant physician in Pulmonology, Hospital Gral. de Agudos Dr. E. TornĂş

https://doi.org./10.56538/ramr.PHVI8364

Correspondencia : DarĂo R. Rey E-mail: darioraul.rey@gmail.com

Received: 12/9/2021

Accepted: 8/2/2022

The possibility exists that the global

workforce, which is approximately 140 million people, may suffer from an

occupational disease in practically every task it performs.1

However, despite that risk in the working population, few

published studies have estimated the incidence of these lesions or diseases,

their final cost in terms of medical expenses, the health of the affected indiÂvidual

and economic losses related to hours of work. Methodological failure,

inconsistency between the members of the research population or poor records

are factors that cause differences in the notification of occupational diseases

and probably contribute to this situation.2

As a consequence of changes in

manufacturing practices and the use of new materials, occupational medicine

specialists continue describing associations between new types of exposure and

chronic forms of diffuse parenchymal lung disease (DPLD). In order to

understand the association between expoÂsure and disease, specialized

physicians must see a high index of suspicion regarding the potential toxicity

of occupational and environmental exposure.

The diffuse interstitial lung

disease (DILD) related to the inadequate exÂposure or poor protection of

workers in different tasks, such as the usufruct of coal and asbestos deposits,

construction, manufacturing, work in shipyards and quarries, and agricultural

work, has been recognized as an occupational risk a long time ago.

Interstitial lung diseases caused

by exposure to substances present in the workplace (OCCUP DILDs) are a group of

significant, preventable diseases. Many different agents cause

the OCCUP DILD, some of which are correctly defined, and some have been poorly

characterized. The list of causative agents keeps growing. Once considered as

“pneumoconiosis”, the list of known causes of OCCUP DILD extends far beyond

coal, silica and asbestos. Clinical, radiological and pathological

presentations of OCCUP DILD are similar to the non-work-related forms of the

disease due to the complex list of pulmonary depuration and repair of the lesion.

The attending physician must have a high index of suspicion and keep a detailed

occupational record in order to look for potential exposure whenever he/she

sees a patient with a DILD. Recognizing an OCCUP DILD is especially important

due to the implications related to primary and secondary prevention of diseases

among the exposed co-workers of the index case.

A study of the American Thoracic

Society pubÂlished in 2019 collected a literature review and data summary

regarding the occupational contriÂbution to the burden of the main

non-malignant respiratory diseases. The purpose of the study was mainly to

inform about diffuse interstitial fibrosis, hypersensitivity pneumonitis, sarcoidosis and other non-infectious, granulomatous

diseases.

The result indicated that

exposure in the workÂplace contributes essentially to the presence of multiple

chronic respiratory diseases, for example: asthma (16%), COPD (14%), chronic

bronchitis (13%), idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (26%), hypersensitivity

pneumonitis (19%), granuloÂmatous diseases, including sarcoidosis (30%), pulmonary

alveolar proteinosis (29%) and

tuberculosis (2.3% in cases of silica exposure).

The conclusion of the study

establishes the urgent need to improve clinical suspicion and knowledge of the

public health regarding the contribution of occupational factors.3

Litow et al classify the OCCUP DILDs into four conditions (frequently

overlapped from the clinical point of view):

A. Pneumoconiosis,

defined as non-cancer pulÂmonary reaction to inhaled mineral or organic

dusts and resulting modification of the parenÂchyma structure.

B. Hypersensitivity

pneumonitis (HN), also known as “extrinsic allergic alveolitis”.

SubstanÂtial number of disorders of the organism’s immune response to the

inhalation of organic or chemiÂcal antigens, associated with histopathological, granulomatous-like changes.

C. Granulomatous diseases with

reaction of foreign body or chronic, immune diseases.

D. Interstitial diffuse

fibrosis, as a reaction to a severe pulmonary lesion, including the

inhalation of irritants.4

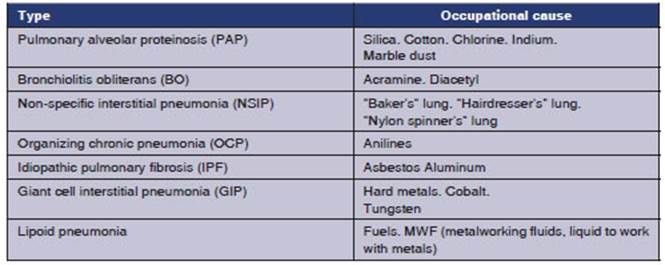

The following table shows some of

the numerÂous examples of OCCUP DILDs. Given the fact that a lot of cases in

the literature are referred to as exceptional, we should consider individual proÂpensity,

thus it may occur that one causative agent causes different pulmonary

interstitial responses.

The most widely known paradigms

of OCCUP DILDs are SILICOSIS and ASBESTOSIS. The acute form of silicosis may

adopt a pattern similar to pulmonary alveolar proteinosis

(PAP), whereas the non-tumor clinical form of asbestosis can be manifested as

an idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF).

OCCUP DILD SIMILAR TO PAP

PAP is an exceptional disease. Both

the surfactant secreted by the huge number of type II pneumoÂcytes

and the imperfect removal of the surfactant by alveolar macrophages play a role

in the physÂiopathology of this condition.

PAP is classified into two

essential forms: conÂgenital or acquired. The most common

variant is the acquired, and is divided into two sub-classes, autoimmune and

secondary, related to a causal factor. Acquired autoimmune PAP is the

most comÂmon. Secondary PAP is related to chronic inflamÂmatory processes,

tumors, hematologic diseases, immunosuppressor

syndromes, and inhalation of inorganic or organic particles.

Abraham and McEuen

studied twenty-four cases of PAP through optical and electron miÂcroscopy to

check if the PAP was associated with silica exposure. A large number of birefringent particles was found in 78% of the cases, as

opposed to control groups.

The environmental history that

was researched correlated well with the results of analyzed parÂticles, for

example, silica “sandblasting”, metal fumes in welders and cement particles.5

Silicosis is generally a chronic

pneumoconiosis. It is not common for the silicosis to adopt an acÂcelerated or

acute form; there aren’t many pubÂlications due to its low frequency of

presentation.

The accelerated variant occurs

between 5 to 10 years after exposure to dust with high concentraÂtions of

silica and if the person didn’t wear respiÂratory protection.

The acute variant is developed a

few years after very intense, brief exposure. It is similar to PAP, due to the

accumulation of lipoprotein PAS (periÂodic acid-Schiff) positive material in

the alveolar spaces; and the chest CT shows the radiographic crazy paving

pattern. It is difficult to differentiate silicoproteinosis

from PAP; the right thing to do is to have good occupational anamnesis. A

whole-lung lavage may delay the unfortunate evolution of this form of

silicosis.6-8

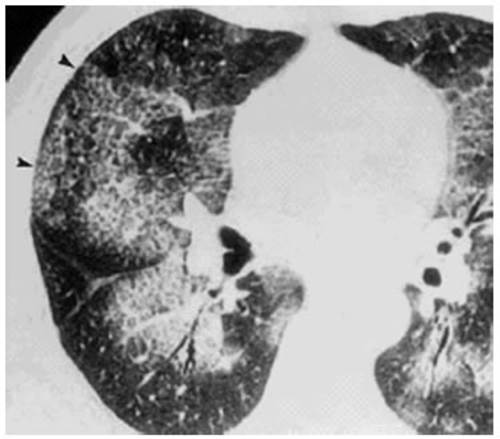

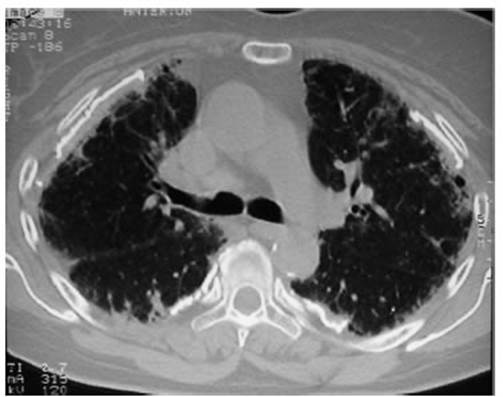

Attached is a case report of a

worker who perÂformed sandblasting of metal pieces for five years without

personal protection (he was unaware of the risk). Dyspnea FC IV and severe

hypoxemia were observed, and the chest CT showed the crazy paving pattern. The evolution

was fatal (Figures 1 and 2).

There are some publications in

the literature where the form of OCCUP DILD similar to PAP is induced by the

inhalation of indium (used in the electronic industry), aluminum (for the

industry of metallization, ship construction, used as dust or for welding),

cotton dust (it can be used in cotton bale carding machines), titanium (used by

paintÂers, mechanics, artificial jewelry manufacturers and titanium dioxide

producers); and there is a case report published in 2018 regarding years of

chronic inhalation of chlorine (used for tanning leather in a tannery).9-15

Recent epidemiological

research suggests that occupational and environmental exposure, as well as the

inhalation of irritants, contribute to cases of IPF, which then ceases to be

idiopathic.

Exposure to asbestos may create

radiographic and histopathological changes similar to

IPF.17

We should also include smoking, sawdust or wood dust, silica,

aluminum, and agricultural activities. The genetic variation among the

population may explain the differences in the susceptibility of the

presentation of varied patterns of interstitial disÂeases, even with the same

causative agent.

Between 1997 and 2000, Ekström et al invesÂtigated the effects of smoking in

occupational exÂposure and found that the fact of being a smoker represented a

great danger of developing severe forms of IPF, as well as a direct

relationship beÂtween the smoking load and higher risks.18

It is possible that in many IPF

patients, the fibrosis isn’t idiopathic because it was caused by occupational

exposure. Misdiagnosis can be due to inadequate anamnesis or lack of evident

suspicion in the causative agent. Some examples of the types of exposure that

contribute to the IPF pathogenia are: organic dust in

agriculture, livestock farming, metal, wood and asbestos dust.

One study conducted in Italy in

2008 found two groups of activities with a particularly high risk of developing

UIP that increased as long as the occupational exposure continued: gardeners,

veterinarians, farmers and metal workers. People who had their own experience

with exposure to the inhaled agent had a higher risk of developing UIP.19

Siderosis is the accumulation of excess iron oxÂide in the alveolar macrophages,

and was described in 1946 by Buckell et al.20

Gothi et al published a case report of

a welder with IPF associated with siderosis who had

been exposed for 40 years to metal fumes; and confirmed that it was originated

by siderosis through transbronchial

biopsy, with moderate functional loss one year after diagnosis, but without

major changes in the chest CT.21 AnÂother similar report is that

of McCormick et al, in which a patient showed IPF secondary to siderosis even though he had worn a welder’s protective

mask for 20 years.22

For a long time, it was thought

to be pneumoÂconiosis with “benign” evolution, given the lack of signs, symptoms

or fibrosis. It is also known as “arc-welders disease” because of the

aspiration of welding fumes with poor respiratory protection or without any

protection at all.23

Aluminum dust has also been an

IPF producer; there are publications about it in the literature. In 1990, Jederlinic et al published 9 cases of workers from a

factory of abrasives, with a mean exposure of 25 years. Radiographic and

functional findings were followed up with biopsy, confirming pulmoÂnary

aluminosis.24

In 2014, Raghu et al published a

similar case of IPF caused by aluminum with bad evolution in a worker who had

mechanized, sanded, drilled and rectified Corian for

16 years. This is a synthetic material consisting of one third of acrylic resin

and two thirds of aluminum trihydrate. Due to the

fact that it is thermoformable and acid-resistant, it

is used for the manufacture of kitchen and bathroom countertops and counters.25

Sawdust, in the form of inhalable

particles, can deposit on the pulmonary parenchyma and damage the workers’

health.

It is known that sawdust is

carcinogenic to huÂmans. Hancock et al carried out a meta-analysis of 85

studies in order to identify researches. The auÂthors showed an elevated risk

in workers exposed to sawdust, and a lower risk in those who worked with soft

wood. The study provided important certainty of this occupational cancer,

suggesting a different effect between hard and soft woods.26 The study of Gustafson et al

established that wood dust could contribute to the incidence of IPF. To that end,

they provided a 30-question questionÂnaire to 757 individuals with this

disease, which was answered by 181 of them. Through statistical studies they

found a higher risk among workers who had been exposed to the dust of hard

woods and birch wood.27

Attached is a case report of IPF

caused by asÂbestosis in an individual who worked as an electriÂcian and

manipulated insulation materials for 25 years without personal protection. The

chest CT shows pleural calcifications and peripheral signs of “honeycombing”

(Figure 3).

OCCUP DILD SIMILAR TO COMBINED PULMONARY FIBROSIS AND EMPHYSEMA (CPFE)

In 1990, Wiggins et al published

nine cases of CPFE, but the most important publication about this interstitial disease

was presented by Cottin et al with a cohort of 61

cases in which they emphaÂsized the predominance of the condition in men, its

relationship with smoking, acceptably preserved lung volumes and severely

decreased DLCO (difÂfusing capacity for carbon monoxide). Chest CT: fibrosis or

“honeycombing” in lower lung fields and emphysema in upper fields, with

extremely bad prognosis associated with pulmonary hyperÂtension. Survival is

lower in CPFE, compared to IPF or COPD.28,

29

Workers who manufacture tires may

suffer from pleural or pulmonary diseases because they are exposed to the

powder used to prevent adherence of the vulcanized surfaces of rubber. Vinaya et al published the case of a worker with CPFE who

had been exposed to powder aspiration for 26 years. The development of this

condition has also been associated with the use of agrochemicals30,

31 .

OCCUP DILD SIMILAR TO BRONCHIOLITIS OBLITERANS

Bronchiolitis obliterans

(BO) is an exceptional obÂstructive pulmonary disease of the small airways,

eventually fatal. It is characterized by the fibrosis of terminal and distal

bronchioles and an obstrucÂtive airflow pattern with progressive reduction of

the respiratory function. It is mostly seen as a non-infectious complication

and chronic rejection after lung transplantation. From the occupational point

of view, cases have been published of BO caused by artificial flavors of

popcorn, where diacetyl stands out. Other causes of

BO include exposure to toxins and inhaled gases, nitrogen oxides, sulfur

mustard, fiberglass.

American service members who

served in Iraq and Afghanistan suffered from BO after being exposed to a fire

in a sulfur mine, with elevated levels of SO2,

and possibly to emissions from open burn pits in military bases, where

batteries, plastic and waste had been disposed of by burning with jet fuel. Doujaiji and Al-Tawfiq, published

the case of a patient with BO caused by SO2

exposure in an oil refinery in the Persian Gulf.32,

33

In 1992 there was a series of 22

cases of BO among 257 textile workers in Spain who had been spraying the

fabrics with what seemed to be non-toxic dyes. Similar products caused a minor

situation in Algeria, with one death and 2 severe cases.34,

35

Experimental studies showed that

the textile paint that was used (Acramin FWR and Acramin FWN) was highly detrimental to the respiratory

system.36

Nanoparticles (NPs) are widely

used at presÂent, and, due to their size, they are included in the range of

breathable elements, because they remain in aerial suspension as aerosols. They

are used in the paper, pharmaceutical, paint, and cosÂmetic industries. Cheng

et al published the case of an individual who developed BO after exposure to

titanium NPs in paint. Recent experimental research revealed inflammatory

phenomena and formation of granulomas after unprotected expoÂsure to NPs.37

Cullinan et al published in 2012 six cases of BO in fiberglass workers, five of

which built vessels with that material, and the remaining worker was building a

cooling tower. The procedure was as follows: they had to build glass reinforced

plastic using resin mixed with styrene and phthalate plus methyl acetone

peroxide. The evolution was bad, with one death caused by respiratory failure,

two lung transplants and three survivors with poor lung function.38

On May 2000, the Bureau of

Occupational Health of Missouri, U.S.A, was informed about eight individuals

with BO who worked in a popÂcorn manufacturing plant. The national entity

(NIOSH, National Institute of Occupational Safety and Health) was notified of

this, and 135 workÂers were evaluated through questionnaires and spirometry. 117 workers finished the studies, and had a

respiratory obstruction rate 3.3 times higher than expected, and 2.6 times

higher than expected chronic cough rate.39 Diacetyl

is a volatile, water-soluble compound that vaporizes with heat, and is a

natural component of several foods, including beer and wine. Concentrated

formulae of diacetyl are used in the food industry,

as flavoring agents, and it is estimated that by 1995, 95 tons had been used

per year.40

If inhaled without respiratory protection or an adequate

ventilation, it can cause BO. Studies have been published in this regard.41

Diacetyl-induced BO among workers of the food industry is the most widely known

and published. After reviewing the literature, a publication has been found of

four cases in Brazil: young men, previously healthy, non-smokers. After 1 to 3

years of work without protection, there was obÂstructive spirometric

impairment between 25% and 44% of what was expected, and tomographic studies

showed air trapping, representative of BO, confirmed through biopsy.42

Just like Gulati and Kreiss, the BO diagnosis must include inspiratory and

expiratory chest CT, spirometry, and confirmaÂtory

biopsy can be avoided in case of compatible exposure. The identification of the

causative agent and its cessation is still fundamental for the index case, as

well as prevention among co-workers who participate in similar types of

exposure. Hygiene and safety include the monitoring of environmenÂtal

ventilation, the use of respiratory masks and covering food containers in order

to avoid leaks.43, 44

The notification, study and

follow-up of similar cases produced by diacetyl or

analogous substances in coffee processing plants have been reported by

Reid-Harvey and Bailey.45, 46

OCCUP DILD SIMILAR TO PLEUROPARENCHYMAL FIBROELASTOSIS (PPFE)

PPFE is an exceptional pulmonary

disease, with rare radiological and histopathological

clinical characteristics. Since the 2013 classification, it has been recognized

as an idiopathic interstitial pneumonia resulting from the combination of

visceral pleura fibrosis and fibroelastosis changes

at the subpleural pulmonary parenchyma. The chest CT

provides characteristic images that raise the suspicion of this disease.

Present as a cause of various diseases, there isn’t a unique triggering factor

for PPFE; reports have been published of chemotherapy sequelae,

bone marrow transplant, collagenopathy or as a

consequence of lung transÂplant rejection.47-52

Despite its uncommon incidence

and prevalence, there are some publications that relate the PPFE with exposure

to toxic substances in the workplace. In 2011, Piciucchi

et al published the case of an individual with PPFE who had high exposure to

asbestos; and in 2018, Xu et al published a similar

case report in which both asbestos and silica were associated with this

condition.53, 54

The publication of Okamoto et al

reports the case of a patient with PPFE who works as a dental technician. These

artisans are exposed to an unlimited number of materials such as silver,

cobalt, chrome, nickel, silica, indium and titanium. The prevalence of

pneumoconiosis among them is estimated at 4.5%-23.6%, with a mean exposure of

12.8 to 28.4 years.55-57

However, regarding this

particular disease, cases have been published caused by chronic inhalation of

aluminum in individuals without reÂspiratory protection, such as the reports of

Huang, Chino and Yabuchi. This metal generally proÂduces

OCCUP DILD similar to IPF, but the repair mechanisms of the pulmonary

parenchyma show individual sensitivity that causes this response.58-60

OCCUP DILD SIMILAR TO DESQUAMATIVE INTERSTITIAL PNEUMONIA (DIP)

First described by Averil Liebow et al, the main

characteristic of DIP is the accumulation of macroÂphages both in the lumen and

walls of the alveoli. Patients with this disease are usually heavy smokÂers;

and the masculine gender is predominant. Clinical symptoms are non-specific,

and due to the fact that patients generally respond to treatment with steroids,

this disease has a better prognosis than IPF.61

The literature has published case

reports about work-related DIP. In many cases, the patient is a heavy smoker.

Abraham and Hertzberg studied 62

samples of DIP confirmed by biopsy using electronic microsÂcopy and X-ray

scattering analysis, in search of inÂorganic particles. Seven out of seventeen

analyzed cases had an occupational history of exposure to that type of

elements, and high concentrations of those were found in their biopsies. The

authors certified specific classes of particles in 92% of the patients, that is

why they suggested a relationship between DIP and the worker’s profession.62

Interstitial lung diseases are

not commonly associated with primary aluminum production. OCCUP DILD induced by

aluminum is very rare, but the experience suggests that exposure to metal fumes

and dust may cause diffuse changes in the parenchyma, such as granulomas, PAP

or DIP.63

Lijima et al published the case report of a worker with a smoking load of 60

packs per year who developed DIP caused by aluminum exposure and showed

excellent evolution after corticosteroid treatment and smoking cessation. The

oriented anamnesis revealed certain tasks of aluminum processing that include

melting the metal in molds for engine covers and polishing the pieces.64

Blin et al published the case report of a patient with DIP who had been

exposed to asbestos workÂing as a plumber and then worked as a caster, with

potential exposure to copper, bronze, iron, aluminum and zirconium alloys. He

had a smokÂing history of 30 packs per year, and had quitted 10 years before

the consultation.65

Zirconium is a

corrosion-resistant material used in the aerospace, airline, and nuclear power

industries. Thanks to scientific research tests, it is known that after

repeated use, it may cause a hypersensitivity skin reaction, forming granuÂlomas

of epitheliolid cells. Experimental studies showed

lung alterations such as granulomas and interstitial fibrosis after exposure to

zirconium. There are few publications in humans regarding pulmonary diseases

related to zirconium.66

Kawabata et al studied 31 patients

with DIP of varied etiologies, where 93% of the patients were male smokers.

These patients had been followed-up for more than 99 months. 14 patients who

had been monitored for a longer period showed 5 cases of IPF and 4 of lung

cancer. The conclusion of this study was that, with time, DIP can progress to

IPF, despite the treatment.67

Coal power plants are still an

important source of power supply worldwide, so miners will continue suffering

from pneumoconiosis and dying because of it. After the approval of the Federal

Coal Mine Health and Safety Act of 1969 in the U.S.A., measures were adopted to

restrict exposure, thus causing a persisting reduction in the prevalence of

pneumoconiosis among coal workers in the U.S.A. from 1970 to 2000.68

Jelic et al studied, in 25 autopsies with microsÂcopy and polarized light,

the number of intramacÂrophageal silica particles and

the degree of fibrosis in antracosilicosis, and in 21

cases, respiratory bronchiolitis associated with smoking. The proporÂtion of

particles found was significantly higher in the cases of occupational disease

(331:4 p < 0.001).

The presence of intra-alveolar

macrophages full of particles of different fibrosis levels indicated a new

disease: chronic DIP, as a predecessor of difÂfuse fibrosis and emphysema

related to stone coal. Among smoking miners, smoking-related fibrosis wasn’t

significant in relation to occupational DIP.

Counting the number of

particle-laden macÂrophages in the BAL (bronchoalveolar

lavage) of miners can predict the disease and suggest prevenÂtion measures.69

OCCUP DILD SIMILAR TO LIPOID PNEUMONIA (LP)

LP, caused by the presence of

lipids in the alveoli, is a rare condition. It is classified into two main groups,

depending on the source of the oily subÂstance: exogenous or endogenous. It has

an insidiÂous onset and non-specific respiratory symptoms, such as dyspnea,

fever or cough. Tomographic findings include nodules, ground glass, crazy pavÂing

or consolidation. Since this condition is not suspected, the diagnosis is

delayed or unnoticed. It may simulate many other lung diseases, includÂing

carcinoma. LP is a chronic foreign body reacÂtion, identified with lipid-laden

macrophages. The diagnosis requires a high index of suspicion and may be

confirmed through respiratory samples showing the macrophages. Treatment

guidelines are not properly defined. The aim of the diagnosis in the exogenous

form of the disease is to avoid exposure. Steroids as a therapeutic option seem

promising.70

Normally, exogenous LP is

associated with the accidental inhalation of oil laxatives to treat conÂstipation,

as can be seen in the series of 44 cases of Gondouin

et al, where only 4 patients had an occupational origin.71 Fire-eaters are a workgroup

inside the entertainment industry. Possible comÂplications of their work must

be taken into considÂeration. The normal procedure consists in blowing the pyrofluid against a burning stick, so there’s the risk that

the fire may propagate to the mouth.72

The first description in the

literature about this occupational hazard was related to accidental aspiration

and was reported in 1971. Since then, there were other publications of LP in

fire-eaters. It is easier to make the diagnosis of the clinical condition after

a good patient inquiry.73-76

According to Gentina

et al, fire-eaters use difÂferent pyrofluids, the

most common being the Kerdan, an oil product of

reduced viscosity that unfortunately spreads rapidly through the bronÂchial

tree after accidental inhalation.

Between October 1996 and January

2001, these authors reviewed seventeen subjects, ten of which had been working

as fire-eaters for years. Their mean age was 24.5 years, and they showed

pleural pain (100%), dyspnea (93.3%), fever of more than 38.5°C (93.3%), cough

(66.6%) and hemoptysis (26.6%). One patient suffered an hemodynamic shock and

had to be treated at the ICU, where he/ she developed a pleuropulmonary

infection. Upon discharge, he/she had a good evolution but with sequelae (opacity in the middle lobe and pleural scar).

Complete pulmonary resolution occurred after 14 days in fifteen patients.77

Apparently, according to

consulted publicaÂtions, it is very common for the employees of gas stations to

practice fuel siphonage, which may be a potential

risk of aspirating liquids or vapor. Directed inquiry allows us to suspect the

cause of this particular LP and obtain diagnosis and treatÂment success.78-82

Sometimes, suspicion requires a

thorough inÂquiry. The patient from the study of Dhouib

et al lubricated cars for eight years with an oil spray without any

respiratory protection; this delayed his/her etiologic diagnosis for 2 years.83

Han et al reported three cases of

LP caused by the use of a paraffin aerosol. Their diagnosis was confirmed

through biopsy and through the study of the samples by x-ray diffraction. The

workers had long-term occupational exposure to paraffin, and the environmental

concentration of the product in the workplace was specifically higher than the

levels measured outdoors.84 Very exceptional cases of LP

were caused by herbicides or solvents used for dry cleaning in the laundry.85, 86

In short, a good patient

occupational inquiry is extremely useful because it generally provides us the

key to guide and elucidate the diagnosis.

REFERENCES

1. Blanc PD, Iribarren

C, Trupin L, et al. Occupational expoÂsures and the

risk of COPD: dusty trades revisited. Thorax. 2009;64:6-12.

https://doi.org/10.1136/thx.2008.099390

2. Schulte PA. Characterizing the

burden of occupational injury and disease. J Occup

Environ Med. 2005;47:607-22. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.jom.0000165086.25595.9d

3. Blanc P, Annesi-Maesano

I, Balmes J, et al.- The OccuÂpational Burden of

Nonmalignant Respiratory Diseases An Official American Thoracic Society and

European ReÂspiratory Society Statement. Am J Resp Crit Care Med. 2019;199:1312-35.

https://doi.org/10.1164/rccm.201904- 0717ST

4. Litow

F, Petson E, Bohnker B, et

al. Occupational InterstiÂtial Lung Diseases J Occup

Environ Med. 2015; 57: 1250-5. https://doi.org/10.1097/JOM.0000000000000608

5. Abraham J, McEuen

D. Inorganic particulates associated with pulmonary alveolar proteinosis: SEM and X-ray miÂcroanalysis results. Appl Pathol. 1986;4:138-46.

6. Nakládalová

M, Štěpánek L, Kolek

V, et all. A case of accelÂerated silicosis Occup Med

(Lond). 2018;68:482-4.

https://doi.org/10.1093/occmed/kqy106

7. Hutyrová

B, Smolková P, Nakládalová

M, et al. Case of acÂcelerated silicosis in a sandblaster Ind

Health. 2015;53:178- 83. https://doi.org/10.2486/indhealth.2013-0032

8. Stafford M, Cappa A, Weyant M, et al.Treatment of Acute Silicoproteinosis

by Whole-Lung Lavage. Semin Cardiothorac

Vasc Anesth. 2013;17:152-9.

https://doi.org/10.1177/1089253213486524

9. Cummings K, Nakano M, Omae K, et al. Indium Lung Disease. Chest 2012;141:1512-21.

https://doi.org/10.1378/chest.11-1880

10. Cummings K, Donat W, Ettensohn D, et al.

Pulmonary Alveolar Proteinosis in Workers at an

Indium Processing Facility. Am J Respir Crit Care Med.2010;181:458-64.

https://doi.org/10.1164/rccm.200907-1022CR

11. Omae K, Nakano

M, Tanaka A, et al. Indium lung--case reports and epidemiology. Int

Arch Occup Environ Health. 2011;84:471-7.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s00420-010-0575-6

12. Keller C. Pulmonary alveolar proteinosis in a painter with elevated pulmonary

concentrations of titanium. Chest. 1995;108:277-80.

https://doi.org/10.1378/chest.108.1.277

13. Thind

G. Acute pulmonary alveolar proteinosis due to exÂposure

to cotton dust. Lung India. 2009;26:152-4. https://doi.org/10.4103/0970-2113.56355

14. Miller R, Churg

A, Hutcheon M, et al. Pulmonary AlÂveolar Proteinosis

and Aluminum Dust Exposure. Am Rev Respir Dis

1984;130:312-5. https://doi.org/10.1164/arrd.1984.130.2.312

15. Rey D, Gonzalez J. Pulmonary

alveolar proteinosis secondÂary to chronic chlorine

occupational inhalation. J Lung Pulm Respir Res. 2018;5:100-3.

https://doi.org/10.15406/jlprr.2018.05.00171

16. Travis W, Costabel

U, Hansell, et al. An official American Thoracic

Society/European Respiratory Society Statement: Update of the International

Multidisciplinary Classification of the Idiopathic Interstitial Pneumonias. Am

J Respir Crit Care Med

2013;188:733-48. https://doi.org/10.1164/rccm.201308-1483ST

17. Stufano

A, Scardapane A, Foschino

M, et al. Clinical and radiological criteria for the differential diagnosis

between asbestosis and idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: Application in two cases.

Med Lav. 2020;112:115-22.

18. Ekström

M, Gustafson T, Boman K, et al. Effects of smokÂing,

gender and occupational exposure on the risk of severe pulmonary fibrosis: a

population-based case-control study. BMJ Open 2014;4:e004018.

https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjoÂpen-2013-004018

19. Paolocci

G, Folletti I, Torén

K, et al. Occupational risk facÂtors for idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis in

Southern Europe: a case-control study BMC Pulm Med

2018;18:75. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12890-018-0644-2

20. Buckell M, Garrad J, Jupe

M, et al. The incidence of sideroÂsis

in iron turners and grinders. Br J Ind Med

1946;3:78-82. https://doi.org/10.1136/oem.3.2.78

21. Gothi

D, Satija B, Kumar S, et al. Interstitial Lung

Disease due to Siderosis in a Lathe Machine Worker.

Indian J Chest Dis Allied Sci 2015;57:35-7.

22. McCormick L, Goddard M, Mahadeva R. Pulmonary fibrosis secondary to siderosis causing symptomatic respiratory disease: a case

report. Journal of Med Case Rep 2008; 2:257.

https://doi.org/10.1186/1752-1947-2-257

23. Doig

A, McLaughlin A. X-ray appearances of the lungs of electric arc welders. Lancet

1936;1:771-5. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(00)56868-8

24. Jederlinic

P, Abraham J, Himmelstein J, et al. Pulmonary

fibrosis in aluminum oxide workers. Investigation of nine workers, with

pathologic examination and microanalysis in three of them Am Rev Respir Dis 1990; 142:1179-84.

https://doi.org/10.1164/ajrccm/142.5.1179

25. Raghu G, Xia D, Schmidt R, et

al. Pulmonary Fibrosis Associated with Aluminum Trihydrate

(Corian) Dust) N Engl J Med

2014;370: 2154-6. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMc1404786

26. Hancock D, Langley M, Chia K,

et al. Wood dust exÂposure and lung cancer risk: a meta-analysis Occup Environ Med 2015;72:889-98.

https://doi.org/10.1136/oemed-2014-102722

27. Gustafson T, Dahlman-Höglund A, Nilsson K, et al. Occupational

exposure and severe pulmonary fibrosis. Respir Med 2007; 101:2207-12.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rmed.2007.02.027

28. Wiggins J, Strickland B,

Turner-Warwick M. Combined cryptogenic fibrosing alveolitis and emphysema: the value of high resolution

computed tomography in assessment. Respir Med.

1990;84:365-9. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0954-6111(08)80070-4

29. Cottin

V, Nunes H, Brillet PY, et

al. Combined pulmonary fibrosis and emphysema: A distinct under-recognized

entity. Eur Respir J.

2005;26:586-93. https://doi.org/10.1183/09031936.05.00021005

30. Karkhanis

VS, Joshi JM. Combined pulmonary fibrosis and emphysema in a tyre industry worker. Lung India. 2012;29:273-6.

https://doi.org/10.4103/0970-2113.99116

31. Daniil

Z, Koutsokera A, Gourgoulianis

K. Combined pulÂmonary fibrosis and emphysema in patients exposed to

agrochemical compounds: Correspondence. Eur Respir. J 2006;27:434-39.

https://doi.org/10.1183/09031936.06.0012 4505

32. King MS, Eisenberg R, Newman JH,

et al. Constrictive bronchiolitis in soldiers returning from Iraq and AfÂghanistan.

N Engl J Med. 2011; 365:222-30. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1101388

33. Doujaiji B, Al-Tawfiq JA. Hydrogen

sulfide exposure in an adult male. Ann Saudi Med. 2010;30:76-8.

https://doi.org/10.5144/0256-4947.59379

34. Moya

C, Antó J, Newman-Taylor A. Outbreak of orÂganising pneumonia in textile printing sprayers. LanÂcet.

1994;344:498-502. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(94)91896-1

35. Ould

Kadi F, Mohammed-Brahim B, Fyad A, et al. Outbreak of pulmonary disease in textile dye

sprayers in Algeria. Lancet 1994;344:962-3.

https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(94)92323-X

36. Clottens

F; Verbeken E; Demedts M,

et al. Pulmonary toxÂicity of components of textile paint linked to the Ardystil syndrome: intratracheal

administration in hamsters OcÂcup Environ Med

1997;54:376-87. https://doi.org/10.1136/oem.54.6.376

37. Cheng TH, Ko

FC, Chang JL, et al. Bronchiolitis Obliterans

Organizing Pneumonia Due to Titanium Nanoparticles in Paint. Ann Thorac Surg. 2012;93:666-9.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.athoracsur.2011.07.062

38. Cullinan

P, McGavin CR, Kreiss K, et

al. Obliterative bronchiolitis in fibreglass

workers: a new occupational disease? Occup Environ Med. 2013; 70:357-.9. https://doi.org/10.1136/oemed-2012-101060

39. Kreiss

K, Gomaa A, Kullman G, et

al. Clinical bronchiolÂitis obliterans in workers at

a microwave-popcorn plant. N Engl J Med.

2002;347:330-8. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa020300

40. Harber

P, Saechao K, Boomus C. Diacetyl-induced lung disease. Toxicol

Rev. 2006;25:261-72. https://doi.org/10.2165/00139709-200625040-00006

41. Palmer S; Flake G, Kelly F,

et al. Severe airway epiÂthelial injury, aberrant repair and bronchiolitis oblitÂerans develops after diacetyl

instillation in rats. PLoSOne. 2011;6(3):e17644.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0017644

42. Cavalcanti Zdo R, Albuquerque Filho AP,

Pereira CA, et al. Bronquiolite associada

à exposição a aroma artificial

de manteiga em trabalhadores de uma

fábrica de biscoiÂtos no Brasil J Bras Pneumol. 2012;38:395-9. https://doi.org/10.1590/S1806-37132012000300016

43. Gulati

M,Teng A. Small Airways Disease Related to OcÂcupational

Exposures. Clin Pulm Med

2015;22:133-40. https://doi.org/10.1097/CPM.0000000000000094

44. Kreiss

K. Occupational causes of constrictive bronchiolitis Curr

Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2013;13:167-172. https://

doi.org/10.1097/ACI.0b013e32835e0282

45. Reid-Harvey R, Fechter-Leggett E, Bailey R, et al. The burden of

respiratory abnormalities among workers at cofÂfee roasting and packaging

facilities. FrontPublic Health. 2020; 8:5.

https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2020.00005

46. Bailey R, Cox-Ganser J, Duling M, et al.

Respiratory Morbidity in a Coffee Processing Workplace with Sentinel Obliterative Bronchiolitis Cases. Am J Ind Med. 2015;

58(12):1235-45. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajim.22533

47. Travis W, Costabel

U, Hansell D, et al. ATS/ERS ComÂmittee on Idiopathic

Interstitial Pneumonias. An official American Thoracic Society/European

Respiratory Society statement: update of the international multidisciplinary classificationof the idiopathic interstitial pneumonias. Am

J Respir Crit Care Med.

2013;88:733-48. https://doi.org/10.1164/rccm.201308-1483ST

48. von der Thüsen

J, Hansell D, Tominaga M,

et al. PleuroÂparenchymal fibroelastosis

in patients with pulmonary disease secondary to bone marrow transplantation.

Mod Pathol. 2011;24:1633-9.

https://doi.org/10.1038/modÂpathol.2011.114

49. Beynat-Mouterde

C, Beltramo G, Lezmi G, et

al. PleuÂroparenchymal fibroelastosis

as a late complication of chemotherapy agents. Eur Respir J. 2014;44:523-7.

https://doi.org/10.1183/09031936.00214713

50. Enomoto Y, Nakamura Y, Colby T, et al. Radiologic pleuropaÂrenchymal fibroelastosis-like lesion in connective tissue disÂease-related

interstitial lung disease PLoS ONE. 2017;12:

e0180283. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0180283 J

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0180283

51. Jacob J, Odink A, Brun AL, et al. Functional

associations of pleuroparenchymal fibroelastosis

and emphysema with hypersensitivity pneumonitis. Respir Med. 2018;138: 95- 101.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rmed.2018.03.031

52. Hirota T, Fujita M, Matsumoto T, et al. PleuroparenÂchymal fibroelastosis as a manifestation of chronic

lung rejection? Eur Respir

J. 2013;41:243-5. https://doi.org/10.1183/09031936.00103912

53. Piciucchi

S; Tomassetti S:; Cason G y col. High resolution CT

and histological findings in idiopathic pleuroparenÂchymal

fibroelastosis: Features and differential diagnosis. Respir Res 2011;12:111.

https://doi.org/10.1186/1465-9921-12-111

54. Xu

L, Rassaei N, Caruso C. Pleuroparenchymal

fibroÂelastosis with long history of asbestos and

silicon exÂposure. Int J Surg

Pathol. 2018;26:190-3.

https://doi.org/10.1177/1066896917739399

55. Okamoto M, Tominaga M, Shimizu S, et al. Dental TechniÂcians'

Pneumoconiosis Intern Med. 2017;56:3323-6. https://doi.org/10.2169/internalmedicine.8860-17

56. Kahraman

H, Koksal N, Cinkara M, et

al. PneumoconioÂsis in dental technicians: HRCT and pulmonary function

findings. Occup Med (Lond).

2014; 64:442-7. https://doi.org/10.1093/occmed/kqu047

57. Ergün

D, Ergün R, Ozdemir C,

et al. Pneumoconiosis and respiratory problems in dental laboratory

technicians: analysis of 893 dental technicians. Int

J Occup Med Environ Health. 2014; 27:785-96.

https://doi.org/10.2478/s13382-014-0301-9

58. Huang Z, Li S, Zhu Y, et al. PleuroparenchymalfibroelasÂtosis

associated with aluminosilicate dust: a case report Int J Clin Exp

Pathol. 2015;8:8676-9.

59. Chino H; Hagiwara E; Midori S

y col. Pulmonary AlumiÂnosis Diagnosed with In-air Microparticle Induced X-ray Emission Analysis of Particles

(Intern Med 2015;54:2035- 40. https://doi.org/10.2169/internalmedicine.54.4246

60. Yabuuchi Y, Goto H, Nonaka M, et al. A case of airway aluminosis with likely

secondary pleuroparenchymal fibroelastosis.

Multidiscip Resp Med 2019; 14:15. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40248-019-0177-4

61. Liebow

A, Steer A, Billingsley J. Desquamative interstitial

pneumonia. Am. J. Med. 1965;39:369-404.

https://doi.org/10.1016/0002-9343(65)90206-8

62. Abraham J, Hertzberg M.

Inorganic particulates asÂsociated with desquamative

interstitial pneumonia. Chest.1981; 80:67e70.

https://doi.org/10.1378/chest.80.1_ Supplement.67S

63. Taiwo

O. Diffuse Parenchymal Diseases Associated With Aluminum Use and Primary

Aluminum Production. J OcÂcup Environ Med. 2014

May;56(5 Suppl):S71-2.

https://doi.org/10.1097/JOM.0000000000000054

64. Iijima Y, Bando M, Yamasawa H, et al. A case of mixed dust pneumoconiosis with desquamative

interstitial pneumonia-like reaction in an aluminum welder. Resp

Case Rep 2017; 20:150-3, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rmcr.2017.02.002

65. Blin

T, De Muret A, Teulier M,

et al. Desquamative inÂterstitial pneumonia induced

by metal exposure. A case report and literature review Sarcoidosis.

Vasc Diffuse Lung Dis.2020;37:79-84.

66. Werfel U, Schneider J, Rödelsperger K, et al. Sarcoid

granuÂlomatosis after zirconium exposure with

multiple organ involvement Eur Respir

J. 1998; 12:750. https://doi.org/10.1183/09031936.98.12030750

67. Kawabata Y, Takemura T, Hebisawa A, et al. Desquamative interstitial pneumonia may progress to lung fibrosis as characterized radiologically. Respirology

2012;17:1214-21. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1440-1843.2012.02226.x

68. Cohen R, Petsonk

E, Rose C, et al. Lung Pathology in U.S. Coal Workers with Rapidly Progressive

Pneumoconiosis Implicates Silica and Silicates. Am J Respir

Crit Care Med 2016;193:673-80.

https://doi.org/10.1164/rccm.201505-1014OC

69. Jelic T, Estalilla O, Sawyer-Kaplan P, et

al. Coal mine dust desquamative

chronic Interstitial pneumonia: A precursor of dust-related diffuse fibrosis

and of emphysema. Int J OcÂcup

Environ Med 2017;8:153-65. https://doi.org/10.15171/ijoem.2017.1066

70. Hadda

V, Khilnani G. Lipoid pneumonia: an overview Expert

Rev. Resp. Med. 2010;4:799-807. https://doi.org/10.1586/ers.10.74

71. Gondouin

A, Manzoni P; Ranfaing E, et al. Exogenous lipid

pneumonia: a retrospective multicentre study of 44

cases in France. Eur Respir J. 1996; 9 :1463-9.

https://doi.org/10.1183/09031936.96.09071463

72. Bankier

A, Brunner C, Friedrich L, Lomoschitz F, Mallek R, Reinhold M. Pyrofluid

inhalation in "Fire-eaters": SeÂquential findings on CT. J Thorac Imaging. 11999;14:303-6. https://doi.org/10.1097/00005382-199910000-00012

73. Gerbeaux

J, Couvreur J, Tournier G,

et al. Une cause rare de pneumatocele

chez l'enfant: L'ingestion d'hydrocarbures (kerdane). Ann

Med Interne (Paris). 1971;122: 589-96.

74. Beermann

B, Christensson T, Moller P, et al. Lipoid pneumoÂnia:

an occupational hazard of fire eaters Brit Med J. 1984; 289:1728-9.

https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.289.6460.1728

75. Şahin

F, Yıldız P. Fire Eater's Pneumonia: One of

the Rare Differential Diagnoses of Pulmonary Mass Images. Iran J Radiol. 2011; 8:50-2.

76. Behnke

N, Breitkreuz E, Buck C, et all. Acute respiratory

distress syndrome after aspiration of lamp oil in a fire-eater: a case report. JMed Case Rep. 2016; 10:193.

https://doi.org/10.1186/s13256-016-0960-1

77. Gentina

T, Tillie-Leblond I, Birolleau

S, et al. Fire-Eater's Lung Seventeen Cases and a Review of the Literature. MedÂicine.

2001; 80:291-97. https://doi.org/10.1097/00005792-200109000-00002

78. Gowrinath

V, Shanthi V, Sujatha G, et

al. Pneumonitis folÂlowing diesel fuel siphonage. Resp Med Case Rep. 2012;5:9- 11.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rmedc.2011.11.010

79. Prasad KT, Dhooria S, Bal A, Agarwal R, Sehgal IS. An Unusual

Cause of Organizing Pneumonia: Hydrocarbon Pneumonitis. J Clin

Diagn Res. 2017;11(6):OD03-OD04.

https://doi.org/10.7860/JCDR/2017/24194.10008

80. Yampara Guarachi

GI, Barbosa Moreira V, Santos FerÂreira A, Sias SM, Rodrigues CC, Teixeira GH. Lipoid pneumonia in a gas station attendant. Case Rep Pulmonol. 2014;2014:358761. https://doi.org/10.1155/2014/358761

81. Venkatnarayan

K, Madan K, Walia R, Kumar

J, Jain D, Guleria R. "Diesel siphoner's lung": Exogenous lipoid pneumonia following

hydrocarbon aspiration. Lung India. 2014;31(1):63-6.

https://doi.org/10.4103/0970-2113.125986

82. Shrestha

TM, Bhatta S, Balayar R, Pokhrel S, Pant P, Nepal G. Diesel siphoner's

lung: An unusual cause of hydrocarbon pneumonitis. Clin

Case Rep. 2020;9(1):416-9. https://doi.org/10.1002/ccr3.3545

83. Dhouib

F, Hajjaji M, Jmal Hammami K, et al. Occupational Exogenous Lipoid Pneumonia:

A Commonly Delayed DiagÂnosis. Respir Case Rep. 2019;8: 6-9.

https://doi.org/10.5505/respircase.2019.19971

84. Han C, Liu L, Du S, et al. Investigation

of rare chronic lipoid pneumonia associated with occupational exposure to

paraffin aerosol. J Occup Health. 2016;58:482-8.

https://doi.org/10.1539/joh.16-0096-CS

85. Hotta

T, Tsubata Y, Okimoto T, et

al. Exogenous lipoid pneumonia caused by herbicide inhalation. Respir Case Rep.

2016;4 e00172. https://doi.org/10.1002/rcr2.172

86. Park S, Park J, Lee J. A case

of lipoid pneumonia associated with occupational exposure to solvents in a

dry-cleaning worker. RespirCase Rep. 2021;,9 e00762. https://doi.org/10.1002/rcr2.762