Autor : De Vito, Eduardo L.1-2

1Instituto de Investigaciones MÃĐdicas Alfredo Lanari, Faculty of Medicine, University of Buenos Aires. 2Centro del Parque, Respiratory Care, Buenos Aires, Argentina.

https://doi.org./10.56538/ramr.UUFV3942

Correspondencia :Eduardo L. De Vito. E-mail: eldevito@gmail.com

ABSTRACT

This article analyzes certain

evolutionary aspects of gas exchange, lung development, the respiratory pump,

the acid-base status and control of ventilation in relation to a significant

event: the passing from aquatic to terrestrial life. By studying this, we can

understand certain aspects that are present in the clinical practice: Why do

people with extreme respiratory muscle weakness breathe as frogs? (frog breathing); why do newborns with breathing difficulties

have nasal flaring and expiratory grunting?; how is it possible that abdominal

muscles, which are typically expiratory, assist with inspiraÂtion in cases of

diaphragmatic paralysis?; why does the breathing pattern of respiratory failure

has less variability and becomes more rigid? and, finally,

is it possible to imagine a neutral pH that doesnât have the 7.0 value?; whatâs

the use of this knowledge, and how should gases in hypothermia be interpreted?

Water-to-land transition is one

of the most important and inspiring major transitions of vertebrate evolution.

Given the amazing diversity of living organisms, it is tempting to imagine an

enormous amount of evolutionary adaptation processes to solve the different

challenges of living on earth faced by each species. There are certain early development

processes that share some crucial factors, and some of the close and distant

gene regulatory networks are conserved. We are witnesses of clinical findings

that serve as testimony of the species that lived in remote times and left us

their evoÂlutionary history.

Key words: Acid-base equilibrium, Hypothermia, Imidazole, Biological evolution,

Respiratory paralysis, Respiratory center

RESUMEN

Este artículo analiza ciertos aspectos evolutivos

en el intercambio gaseoso, el desaÂrrollo pulmonar, la bomba respiratoria, el

estado ácido-base y el control de la ventilaÂción en

relación con un evento trascendente: el pasaje de la vida

acuática a la terresÂtre. Su estudio puede permitir comprender ciertos

aspectos con los que lidiamos en la práctica clínica: ÂŋPor

qué las personas con debilidad muscular respiratoria extrema respiran

como ranas (respiración frog)?, ÂŋPor

qué los recién nacidos con dificultad respiratoria tienen aleteo

nasal y quejido espiratorio?, Âŋcómo es posible que los músÂculos

abdominales, típicamente espiratorios, asistan a la inspiración

en casos de la parálisis diafragmática?, Âŋpor qué en la

insuficiencia respiratoria el patrón respiratorio tiene menos

variabilidad y se torna más rígido? y, por último, Âŋes

posible imaginar un pH neutro que no tenga el valor de 7,0, para qué

sirve este conocimiento y como se deben interpretar los gases en hipotermia?

La transición del agua a la tierra es una de las

más importantes e inspiradoras de las grandes transiciones en la

evolución de los vertebrados. Ante la sorprendente diversiÂdad de

organismos vivos, es tentador imaginar una cantidad enorme de adaptaciones

evolutivas para resolver los diferentes desafíos que cada especie tiene

para la vida en la tierra. Hay desarrollos tempranos que comparten algunos

factores cruciales y algunas de las redes genéticas regulatorias

cercanas y lejanas están conservadas. Somos testigos de hallazgos

clínicos que son el testimonio de especies que han vivido en

épocas remotas y nos han legado su historia evolutiva.

Palabras clave: Equilibrio ácido-base, Hipotermia, Imidazol,

Evolución biológica, Parálisis respiratoria, Centro

respiratorio

Received: 6/20/2022

Accepted: 8/9/2022

Plus ça change, plus câest la même chose.

Alphonse Karr (1808-1890)

The objective of this article is

to analyze certain breathing-related evolutionary aspects, particuÂlarly gas

exchange, lung development, the respiÂratory pump, the acid-base status and

control of ventilation in relation to a significant event: the passing from

aquatic to terrestrial life.

By studying this, we can

understand certain aspects that are frequently present in the clinical

practice: Why do people with extreme respiraÂtory muscle weakness breathe as

frogs? (frog breathing); why do newborns with breathing diffiÂculties have

nasal flaring and expiratory grunting?; how is it possible that abdominal

muscles, which are typically expiratory, assist with inspiration in cases of

diaphragmatic paralysis?; why does the breathing pattern of respiratory failure

has less variability and becomes more rigid (apart from being fast and

superficial)? and, finally, is it possiÂble to imagine

a neutral pH that doesnât have the 7.0 value?; whatâs the use of this

knowledge, and how should gases in hypothermia be interpreted?

Water-to-land transition is one

of the most imÂportant and inspiring major transitions of verteÂbrate

evolution. The first fish appeared 438 million years ago, and the transition of

the tetrapod from water to land occurred around 375 million years ago; tetrapods were the main characters of this unique event:

they emerged from the water and breathed air. They were exothermic and

incapable of sustaining high levels of physical activity, and evolved into two

classes of vertebrates with high levels of maximal oxygen consumption: mammals

and birds.1 Terrestrial

ability appears to coincide with the origin of limbs; there was a coexistence

of aquatic features, such as the gills and tail fin with the limbs.2

CHANGES IN THE COMPOSITION OF GASES IN THE BIOSPHERE

Fluctuations in O2

and CO2 levels in the

biosphere have determined the way and means through which O2

was incorporated and CO2

was elimiÂnated. During the late Paleozoic era (around 300

million years), for a period of approximately 120 million years, the O2 level

increased to a maximum of 35% and then dropped abruptly to a minimum of 15% in

the Triassic. These changes doubled in the water and resulted in great events,

such as mass extinctions.

The highest CO2

levels occurred in the OrÂdovician and Silurian periods, whereas

in the Carboniferous, the CO2 level had

decreased to the current value (0.036%), although at the end of the Permian it

had increased by a factor of three. The structure and function of initial gas

exchangers were produced mostly by natural selection under environmental

conditions that were totally diffeÂrent from the current ones.3

THE AQUATIC AND TERRESTRIAL ENVIRONMENTS

The gasometric

composition of air is well-known by us. Oxygen in seawater derives mostly from

the air, so it is composed of the same gases of the atmosphere. Since the

oxygen is more soluble in water than nitrogen, there is a higher proportion of

oxygen in water than in the air. But from the point of view of dissolved oxygen

(molecular), the air has 210 cmÂģ of O2/L, and seawater contains only 9 cmÂģ/L. So, in general terms, dissolved oxygen is much

less abundant in water than in air.

The presence of macro- and

microalgae contriÂbutes directly with lighting to the oxygenation of seawater.

Only 1% of the light that has an impact on the surface of the sea reaches 200 m

of depth (photic zone).4

Thus, O2 availability

decreases significantly as water depth increases.

GAS EXCHANGE

The most significant modification

in gas exchange was produced as a consequence of the change in the structure of

teguments. Gas exchange in waÂter was produced by two routes: teguments and

incipient respiratory structures. With the passing to terrestrial life and the

appearance of scales (repÂtiles), teguments would provide protection against

desiccation, but would become less permeable to gas exchange.

In birds and mammals, the

feathers and fur proÂhibited skin gas exchange for good. That function would

then be exclusively performed by the lung, with air inlet through the mouth.

The alveolar air started to form, an intermediate station between atmospheric

air and blood, with remarkably stable gasometric

composition, temperature and humiÂdity. So the lungs of mammals evolved in

order to face a unique set of challenges:

â Ensure the sufficient supply of

inspired oxygen to all the pulmonary units whose exchange surÂface would reach

around 70-150 m2 in humans,

inside a confined thoracic space,

â That large gas exchange surface

had to be assoÂciated with a minimum barrier thickness, and,

â A microvascular

network had to be generated to accommodate the cardiac output of the right

ventricle and resist cyclic mechanical tensions, which increase many times from

rest to exercise.

The organs of the respiratory

system of various aquatic animals, such as the fish, are the gills and the

operculum. The opening and closing dynamics of the gills is controlled by the

cranial nerves that derive from the gill arches (trigeminal, facial, and glossopharyngeal).

The innervation of the gill area in frogs is developed from the facial,

glossopharynÂgeal, and vagus cranial nerves.5 Figure 1

shows the morphological aspect of the lungs in vertebrates according to JN

Maina.3

Mammals and birds are the two

large classes of vertebrates that have high levels of maximum oxygen

consumption.1 A significant feature of these two groups is that even

though the physiology of the cardiovascular, renal, gastrointestinal, endocriÂne

and nervous systems shows many similarities, the lungs are radically different.6

Our perspective of self-aware

mammals could make us think that we have been more successful than birds.

Taking into account other aspects, it seems to be quite the opposite. West and

Watson proposed that the lung of birds is superior to that of mammals, and that

evolution in mammals has gone the wrong way:1

âĒ An important difference is the

fact that the ventilation of the gas exchange area (West resÂpiratory zone) has

a continuous flow pattern in birds, but shifts in mammals.

âĒ Birds move the gases through

convection, whereas mammals also need diffusion in the terminal airways.7

âĒ Birds have a more uniform

parenchyma with small terminal spaces that are largely intertwiÂned with the

capillaries, minimum membrane thickness and ultimately, more efficient gas

exchange.

âĒ Birds have separated the ventilatory and gas exchange functions, they seem to be

less vulÂnerable to bronchoaspiration and their

oxygen consumption in relation to their body weight is higher than that of

mammals.

For all those reasons, from a

structure-function standpoint, the bird lung is superior.1

Humans werenât the evolution goal (evolution doesnât have a

goal), still less the mammal lung. Evolution occurs gradually, not necessarily

towards more complex structures.8

In view of the great development

of his brain, the man is an acutely self-aware creature, more immensely capable

than any other animal of taking advantage of the individual and social

experience. While a climber struggles to get to the top of the Everest, the

geese are waiting for him, flying over his head.

THE RESPIRATORY PUMP

Evolution to terrestrial life

limited the gas exÂchange to the lungs, which evolved into a large exÂchange

surface exposed to a very much controlled alveolar air that had to be moved (ventilated)

in order to take air from the atmosphere. The respiÂratory pump, with its

different versions, was in charge of this.9

Figure 2 shows a graphic

representation (denÂdrogram) of several groups of

vertebrates in relaÂtion to the strategy used regarding the respiratory pump.9 We can

observe the change from a buccal pump driven

by branchiomeric (of the pharynÂgeal tract) and hypobranchial muscles (larynx, tongue, jaw) innervated by

cranial nerves to a thoracic-abdominal aspiration pump driven by axial

muscles innervated by spinal nerves with premotor neurons situated in the

ventral respiÂratory column.

The first steps in the evolution

of air-breathing were a modification of the behavior at the surface and changes

in the valves of the mouth/blowhoÂle/nostrils, the operculum and the glottis

(or their equivalent), that is to say, changes in the activation of the

muscles that expand or contract several openings. This allowed both aquatic and

air-breathing. Changes in the muscles of the resÂpiratory pump evolved later.10 So, the

evolution of respiratory mechanisms in vertebrates occurred from aquatic

ventilation promoted mainly by a buccal strength pump

to air ventilation driven mostly by a suction or aspiration pump. Only

mammals have a muscle diaphragm, of axial oriÂgin, innervated by spinal motor

neurons (phrenic nerve) and not by cranial nerves.

Between both ends of the buccal and aspiraÂtion pumps, there was the active

expiration (Figure 2, expiratory pump).9

This intermediate mechanism between the buccal pump of fish and amphibians and the aspiration pump

of reptiles, birds and mammals was barely known. It has been proven that many

amphibians use the axial muscles for active expiration along with the buccal pump for active inspiration. This suggests that

aspiration breathing evolved in two steps:

âĒ from buccal pumping alone to buccal

pumping for inspiration and axial muscles for expiration, and then

âĒ aspiration

breathing alone using axial muscles for both expiration and inspiration.

In mammals we can see a change in

the relaÂtive contributions of the chest wall distensibility

and resistance of the airflow to the respiratory effort (the first predominates

in birds and repÂtiles, the latter acquires greater

importance in mammals). We can also observe evolution into a muscle

diaphragm and a decreased need for active lung deflation as the system

returns to the state of equilibrium after inhalation (elastic recoil). Thus,

the functional residual capacity (FRC) is formed, that is the volume remaining

in the lungs at the end of passive expiration that represents the balance

between the forces expanding the lung and the ones that tend to collapse it

(respiratory rest).

In fish, amphibians and most

reptiles, there is certain division between the thoracic and abdomiÂnal

cavities. This partition is incomplete and not very efficient as a respiratory

pump. In developed reptiles and all mammals, there is a complete seÂparation of

the thoracic and abdominal cavities; this separation has a muscular layer in

the case of mammals. So, there is the diaphragm as a muscle and also aspiration

breathing (negative pressure).10

EVOLUTION OF ACID-BASE REGULATION

In humans, the PaCO2 is strictly controlled.

Throughout the day and night and even with the participation of other

non-respiratory functions, PaCO2 varies only

in a few mmHG. Furthermore, unlike the PaO2 that

decreases with age, the PaCO2 remains

constant for life. So any sustained deviaÂtion from the PaCO2

shall be seen as a significant alteration in homeostasis.11

What is the importance of such a

strict control of the PaCO2?

And, how is it achieved? The study of the

evolution of vertebrates from aquatic to terrestrial life and the capacity to

regulate body temperature allows us to understand why the PaCO2

has to be kept within such narrow limits.

In aquatic life under a

poikilothermic dynaÂmic, body temperature isnât constant, it varies according

to room temperature. The PCO2

suffers a great deal of variations and, although it is easily

removed (teguments permeable to CO2),

the main problem is oxygenation (the PO2

of water is lower than the atmospheric one), and due to various

reÂasons we will see later on, it is impossible to keep a constant pH value.

In terrestrial life, on

the other hand, the peripheral chemoreceptors (PQRs) stop working due to high

room PO2 (they

are sensitive to PaO2 below 60

mmHg), body temperature can be kept constant (homeothermia),

but now the sole CO2 elimination

route is expired air (due to the deveÂlopment of teguments that prevent

desiccation).

With a well-developed

thermoregulation caÂpacity and the precise regulation of PaCO2, the resulting, remarkably stable pH

allows mammals to maintain the ionization of the enzymes and the products of

internal metabolism, so that they are kept inside the

cell (the enzymes would escape from the cell if they lost ionization). This

strategy is called pH-stat: it is extremely important for homeotherms

to keep a constant pH (very narrow limits). Metabolic intermediates and enzymes

are completely ionized in the region that is close to neutral pH (neutral pH

from 7.0 to 25 °C) and have a low tendency to escape from the cell by going

through the membranes.

In other words, if the room pH

gets far off the ionization window of metabolic intermediates, these would lose

their charge and escape the cell. Hence the importance of

keeping the pH constant (pH-stat). This was elegantly expressed

as âthe importance of being ionizedâ.12

In order to understand why this

strategy isnât effective in poikilotherms, it is

important to menÂtion a fact that isnât usually taken into account: a body

temperature of 37 °C doesnât suggest a relaÂtionship between temperature and pH

(except in certain cases such as accidental or therapeutic hyÂpothermia): Temperature

changes the pH neutraliÂty value due to changes in the equilibrium constant of

water or kW (ion product of water). Thus, pure water has a neutral pH (value of

7.0) only at 25 °C, whereas at 10 °C and 35 °C, the neutral pH value is 7.27

and 6.98, respectively*.

In water, at low temperatures,

the internal pH of poikilotherms (fish, amphibians,

reptiles) tends to increase and consequently becomes far off the ionization

window of proteins and enzymes which as buffers can lose ionization but,

fortunately hisÂtidine with its α-imidazole group keeps a constant ionization; so, that

ionization keeps enzymes inÂside the cell and active regardless of temperature

variations. This is the so-called α-stat strategy.12-15

Histidine is a particular amino acid. It has three groups that are capable of

being charged: amine (pK 9.17), carboxyl (pK 1.82) and imidazole (pK 6.0);

and its net charge (or degree of dissociation) remains constant throughout the

whole tempeÂrature range and is the basis of Reevesâ α-stat theory.15

In fact, aquatic poikilotherms appeared long before terrestrial homeotherms and we had to find a homeostatic strategy when

teguments lost permeaÂbility to CO2.

The PCO2 constancy is a

success in terrestrial life and maybe it wouldnât have occuÂrred without the

dramatic complexity developed by the controlling structures of breathing.

But pH constancy in humans is

also the result of the interaction between multiple buffer systems in which

protein systems are found and the exact regulation of the bicarbonate/carbonic

acid system through ventilatory and renal control. It

is evident that all of this has been possible thanks to the evolution of the respiratory

centers.

EVOLUTION OF VENTILATION CONTROL

In the aquatic environment, the

PQRs of poikiloÂtherms are in charge of regulating

ventilation and the level of immersion, minute after minute. Their respiratory

centers consist of groups of relatively simple cells capable of generating a very

simple breathing pattern; for example, amphibians use only two groups of motoneurons that mediate ventilation. Far from acquiring

the phrenic nerve, the first nerves involved in the act of breathing were the

facial and glossopharyngeal.

With the passing to terrestrial

life, the strucÂtures that generate the respiratory rate were now oscillatory

neural networks of six groups of interconnected motoneurons,

and chemoreceptors sensitive to CO2 were

developed. The new neural circuits were stable but responsive to changes in the

levels of O2,

CO2,

pH, exercise, sleep, etc. Also, there needed to be coordination with phonation,

swallowing, airway reflexes, coughing, sniffing and locomotion. Thereâs also

long-term adaptation due to alterations in the thoracic cavity, the lung, and

the respiratory muscles caused by aging, weight gain or loss, pregnancy and

diseases. Finally, the new suprapontine structures

control the respiÂratory muscles voluntarily and in relation to a âevolutionary curiosityâ: emotions.

The model of respiratory centers

in mammals with the pneumotaxic and apneustic centers, the dorsal respiratory group and the

ventral respiraÂtory group, is already part of the history of meÂdicine. This

model arose from cross-section cuts of the trunk of sedated cats, decerebrated at the intercolicular

height, impaired, with or without vagus, and from the

observation of changes in breathing patterns and then from a total of six

transverse sections at different trunk levels.16, 17

At present, itâs impossible to

address the topic of the respiratory centers without speaking about the preBötzinger complex as a critical area for the

generation of the respiratory rate, and the retroÂtrapezoid

nucleus and parafacial respiratory group for the

generation of active expiration and the relationship with non-respiratory

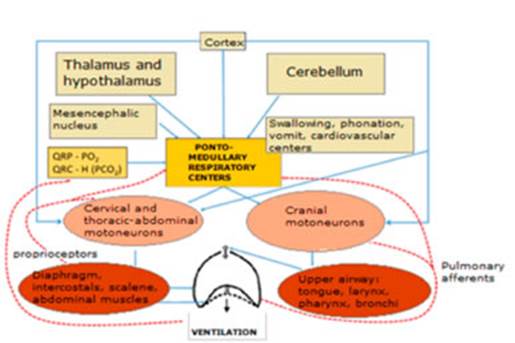

functions.17-20 Figure 3

shows the schematic organization of the respiratory system.

So, the evolution of respiratory control

from fish to mammals is characterized by higher complexity and is related to

the homeostasis of O2,

CO2,

pH and temperature.

â PQRs sensitive to hypoxia (PaO2 ≤ 60

mmHg and highly active under water) stopped functioning in terrestrial areas.

â When the constancy of the PaCO2 and the pH

were prioritized (pH-stat strategy), new areas were developed that were

very sensitive to CO2.

â The simple pacemaker cells gave

place to the preBötzinger complex, as well as

the paraÂfacial respiratory group and retrotrapezoid nucleus.23, 24

â Connections were developed with

non-respiraÂtory functions to coordinate respiration with phonation, swallowing

and vomiting.25

â We have a sort of homunculus

(primary motor area of the cortex, posterior frontal lobe, precenÂtral gyrus) that is

capable of voluntarily comÂmanding respiration over autonomic control.26

â Telencephalization

reached full development in humans. The cortex and subcortical/limbic system

structures (amygdala, cingulate gyrus, hippocampus,

etc.) mediate the emotions and influence respiration.

â The ponto-medullary

respiratory network, which produces the rhythmic central comÂmand for

respiration makes up stable, coordiÂnated and adaptable structures.

CONTROL OF VENTILATION AND ACID-BASE STATUS CLINICAL-EVOLUTIONARY

LESSONS

Only in developed reptiles and

all mammals, there is a complete separation of the thoracic and abdominal

cavities; this separation has a muscuÂlar layer in the case of mammals: the

diaphragm. Thus, aspiration breathing is developed in terrestrial and

aquatic mammals, but our gene pool seems to remember other evolutionary steps.

â Some people with neuromuscular

diseases and important respiratory muscle weakness use the frog breathing,

which allows the inlet of air at positive pressure. Frog breathing at

positive pressure (buccal pump), was

one of the first ventilatory modes of vertebrates.

â Nasal flaring and expiratory

grunting are signs of respiratory difficulties in newborns,27 babies and

toddlers.28 These

indicate an increase in breathing effort. This mechanism is unusual in adults.28 Various coordinated cranial nerves move those

structures and remember breathing with valves of the mouth/blowhole/nostrils

and the operculum and glottis (or their equivalent) like the first

vertebrates.

â In the case of bilateral

diaphragmatic paralysis, the abdominal muscles have an inspiraÂtory action.

Their action reduces the FRC, so in the next inspiration the air enters in a

passive way due to the state of equilibrium of the chest. The abdominal

muscles (expiratory pump) have an inspiratory function in certain

vertebrates.

â The variability of the

breathing pattern is lower in cases of acute respiratory failure. The use

of non-invasive ventilation reestablisÂhes variability and gets close to normal, with higher support levels.29

The rigid breathing pattern with poor variability reminds us

of poikilotherms. Evolution gained complexity and

variability but, with charge increase, the breathing pattern becomes more

rigid.

The use of general body

hypothermia for heart surgery has become a routine procedure. ConÂsequently,

the concept of neutral pH had to be reconsidered, and the experience of

millions of years of our ancestors, the poikilotherms,

had to be taken into account.

â Definition of neutrality (that

belongs to Arrhenius, 1889): it is not a âpH of 7.0â but the presence of

equal amounts of ions H+ and

OHâ. Since

temperature has the same effect on the concentration of each one of them,

neutrality is maintained regardless of temperature.30

â Regardless of the patientâs

temperature, arteÂrial gases are always analyzed at 37°C (it is the temperature

with which PO2,

PCO2 and pH

electrodes are measured). The gases of a hyÂpothermic patient are also analyzed

at 37°C, and if the PO2,

PCO2 and pH values

are within the normal range, the acid-base status of the patient will be

suitable for his/her temperature.31,

32

â The in vitro anaerobically

cooled blood of a mammal follows the acid-base status pattern of a poikilotherm. Physiologically speaking, to correct the

pH according to body temperature in hypothermia doesnât make any sense, because

the neutrality of pH also changes with temperature.

Given the amazing diversity of

living organisms, it is tempting to imagine an enormous amount of evolutionary adaptation

processes to solve the different challenges of living on earth faced by each

species. There are certain early development processes that share some crucial

factors, and some of the close and distant gene regulatory networks are

conserved.

In France, before the

Franco-Prussian War, there was a political satire about government changes that

said: âWe take the same and start againâ. Alphonse Karr (1808-1890)33 added his

famous phrase ÂŦplus ça change, plus câest la même choseÂŧ: the more things change, the more

they stay the same. According to the comparative biology, there seems to be

immutable principles even with evident superficial or morphological

differences. It is heartbreaking to think that we are the sole witnesses of

clinical findings that serve as testimony of the species that lived in remote

times and left us their evolutionary history, our evolutionary history.

Conflict of interest

The author has no conflict of interest to declare.

NOTES

* If the pH increases as

temperature falls, this does not mean that water becomes more alkaline at lower

temperatures. A solution is alkaline if there is an excess of hydroxyl ions

over hydrogen ions (that is to say, pOH > pH). As

long as the concentration of hydrogen ions and hydroxide ions stays the same,

water will still be neutral (pH = pOH), even if its

pH changes. The problem is that we are all familiar with 7.0 being the pH of

pure water (non-ionized), so anything else feels really strange. In order to

calculate the neutral value of pH it is necessary to know the Kw, which

increases with temperature, and if it changes, then the neutral value of pH

changes as well. At 25 °C the Kw (mol2

dmâ6) value is 1.00 x 10â14, the pH is 7.00 and the pOH

is 7.00. So, 7.00 + 7.00 = 14. At 10 °C we will have a

Kw value of 0.681 x 10â14,

pH of 7.08 and pOH of 7.08. So,

7.08 + 7.08 = 14.16. So, the pH of 7.00 and 7.08 at 25 °C and 10 °C,

respectively, is neutral because it has H+

= OHâ.34

REFERENCES

1. West JB, Watson RR, Fu Z. The human

lung: did evoluÂtion get it wrong? Eur Respir J 2007;29:11-17.

https://doi.org/10.1183/09031936.00133306

2. Dickson BV, Clack JA, Smithson

TR, et al. Functional adapÂtive landscapes predict terrestrial capacity at the

origin of limbs. Nature 2021;589:242-5. https://doi.org/10.1038/ s41586-020-2974-5.

3. Maina

JN. Comparative respiratory physiology: the funÂdamental mechanisms and the

functional designs of the gas exchangers. Open Access Animal Physiology 2014;53.

https://doi.org/10.2147/OAAP.S53213

4. Knoll AH, Bergmann KD, Strauss

JV. Life: the first two bilÂlion years. Philos Trans

R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 2016;5:371.

https://doi:10.1098/rstb.2015.0493.

5. Alonso DG. Desarrollo y diferenciación de las

branquias externas e internas en embriones y larvas de Bufo arenaÂrum:

análisis descriptivo y experimental. Tesis de Doctor. Facultad de

Ciencias Exactas y Naturales. Universidad de Buenos Aires. 2003.

http://digital.bl.fcen.uba.ar/Download/Tesis/Tesis_3581_Alonso.pdf

6. Hsia CCW, Hyde DM, Weibel ER. Lung Structure and the Intrinsic Challenges of Gas Exchange. Compr Physiol 2016;6:827-95. https://doi.org/10.1002/cphy.c150028.

7. West JB, Watson RR, Fu Z. The

human lung: did evoluÂtion get it wrong? Eur Respir J 2007;29:11-7.

https://doi.org/10.1183/09031936.00133306.

8. Smith HW. From

Fish to Philosopher. The American Biology Teacher 1962;24::445.

https://doi.org/10.2307/4440034

9. Milsom

WK. Evolutionary Trends in Respiratory MechaÂnisms. In: Poulin,

M.J., Wilson, R.J.A. (eds)

Integration in Respiratory Control. Advances in Experimental Medicine and

Biology 2008;605. Springer, New

York, NY. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-0-387-73693-8_51.

10. Fogarty MJ, Sieck GC. Evolution and Functional DifferentiÂation of the Diaphragm Muscle

of Mammals. Compr Physiol 2019;9:715-66.

https://doi.org/10.1002/cphy.c180012.

11. Arce SC, De Vito EL. More Breathing, Less Fitness: LesÂsons from Exercise Physiology in

Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary DiseaseâHeart Failure Overlap. Am J Respir Crit

Care Med 2017;196:1233-4. https://doi.org/10.1164/rccm.201707-1430ED

12. Rahn

H, Reeves RB, Howell BJ. Hydrogen ion regulation, temÂperature,

and evolution. Am Rev Respir Dis 1975;112:165-72.

13. Wilson RJA, Vasilakos K, Remmers JE.

Phylogeny of verteÂbrate respiratory rhythm generators: the Oscillator HomolÂogy

Hypothesis. Respir Physiol Neurobiol 2006;154:47-60.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resp.2006.04.007

14. Rahn

H. Body temperature and acid-base regulation. Pneumonologie

1974;151:87-94. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02097155

15. Reeves RB. An imidazole alphastat hypothesis for vertebrate acid-base regulation:

Tissue carbon dioxide content and body temperature in bullfrogs. Respir Physiol 1972;14:219- 36. https://doi.org/10.1016/0034-5687(72)90030-8

16. Lumsden

T. Observations on the respiratory centres in the

cat. J Physiol 1923;57:153-60.

https://doi.org/10.1113/jphysiol.1923.sp002052

17. Stella G. On

the mechanism of production, and the physiÂological significance of âapneusisâ. J Physiol 1938;93:10-23. https://doi.org/10.1113/jphysiol.1938.sp003621

18. MacLarnon

AM, Hewitt GP. The evolution of huÂman speech: the role of enhanced breathing

control. Am J Phys Anthropol

1999;109:341-63. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1096-8644(199907)109:3<341::AID-AJPA5>3.0.CO;2-2

19. Sundin

L, Burleson ML, Sanchez AP, et al. Respiratory chemoreceptor function in

vertebrates comparative and evolutionary aspects. IntegrComp Biol

2007;47:592-600. https://doi.org/10.1093/icb/icm076

20. Feldman JL, Del Negro CA,

Gray PA. Understanding the Rhythm of Breathing: So Near, Yet So

Far. Annl Rev Physiol 2013;75:423-52.

https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-physiol-040510-130049

21. Hilaire

G, Pásaro R. Genesis and control of the

respiratory rhythm in adult mammals. News Physiol Sci 2003;18:23-8. https://doi.org/10.1152/nips.01406.2002

22. Bianchi AL, Gestreau C. The brainstem respiratory netÂwork: an overview

of a half century of research. Respir Physiol Neurobiol 2009;168:4-12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resp.2009.04.019

23. Onimaru

H, Homma I. A novel functional neuron group for respiratory

rhythm generation in the ventral medulla. J Neurosci 2003;23:1478-86.

https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUÂROSCI.23-04-01478.2003

24. Feldman JL, Del Negro CA. Looking for inspiration: new perspectives on

respiratory rhythm. Nat Rev Neurosci 2006;7:232-41. 10.1038/nrn1871. https://doi.org/10.1038/ nrn1871

25. Evans KC, Shea SA, Saykin AJ. Functional MRI localization of central nervous

system regions associated with volitional inspiration in humans. J Physiol 1999; 520 Pt 2:383-92.

https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7793.1999.00383.x

26. Nakayama T, Fujii Y, Suzuki K. et al. The primary moÂtor area for voluntary diaphragmatic motion identified by

high field fMRI. J Neurol 2004;251:730-5.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s00415-004-0413-4.

27. Silverman WA, Andersen DH. A controlled clinical trial of effects of water mist on obstructive

respiratory signs, death rate and necropsy findings among premature infants.

Pediatrics 1956;17:1-10.

28. Mas A, Zorrilla JG, García D, et al. Utilidad

de la detecÂción del aleteo nasal en la valoración de la gravedad

de la disnea. Med Intens

2010;34:182-7.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.medin.2009.09.008

29. Giraldo

BF, Chaparro JA, Caminal P,

et al. CharacterizaÂtion of the respiratory pattern variability of patients

with different pressure support levels. Conf Proc IEEE Eng Med Biol Soc 2013;2013:3849-52.

https://doi.org/10.1109/EMBC.2013.6610384

30. Yartsev

A. Alpha-stat and pH-stat models of blood gas interpretation, In Deranged

Physiology. A free online resource for Intensive Care

Medicine. Last updated Tue, 02/08/2022.

https://derangedphysiology.com/main/cicm-primary-exam/required-reading/acid-base-physiology/Chapter%20115/alpha-stat-and-ph-stat-models-blood-gas-interpretation

(accessed 18 June 2022).

31. Williams JJ, Marshall BE. A Fresh Look at an Old Question. Anesthesiology 1982;56: 1-2.

https://doi.org/10.1097/00000542-198201000-00001

32. De Vito EL. Hipotermia [Hypothermia].

Medicina (B Aires). 1987;47:214-6. Spanish.

33. Karr A. Alphonse Karr: âPlus ça change, plus câest la même choseâ. LâHistoire

en citations,

https://www.histoire-en-citations.fr/citations/Karr-plus-ca-change-plus-c-est-la-meme-chose

2016 (accessed 18 June 2022).

34. Clark J. Temperature

Dependence of the pH of pure Water. Chemestry, Libre Texts. Last updated Aug

15, 2020. https://batch.libretexts.org/print/url=https://chem.libretexts.org/Bookshelves/Physical_and_Theoretical_Chemistry_TextÂbook_Maps/Supplemental_Modules_(Physical_and_Theoretical_Chemistry)/Acids_and_Bases/Acids_and_Bases_in_AqueÂous_Solutions/The_pH_Scale/Temperature_Dependence_of_

the_pH_of_pure_Water.pdf (accessed 19 June 2022)