Autor Osejo-Betancourt, Miguel1, Moreno-RamĂrez, Carlos Ernesto2, Chaparro-Mutiz, Pedro3

1Specialist in Internal Medicine, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de Honduras, and in Pulmonology, Hospital Santa Clara, Bogotá, Colombia. 2Specialist in Epidemiology and Resident in Internal Medicine, Hospital Santa Clara, Bogotá, Colombia 3Specialist in Internal Medicine and Pulmonology, Hospital Santa Clara, Bogotá, Colombia.

https://doi.org./10.56538/ramr.FPKS7802

Correspondencia : Miguel Osejo Betancourt. E-mail: mosejob@unbosque.edu.co

ABSTRACT

Pulmonary alveolar proteinosis is

a clinical entity characterized by the accumulation of proteinaceous material,

rich in surfactant, mediated by reduced clearance by alveolar macrophages. In

adult patients, it is commonly associated with autoimmune phenomena resulting

in a deficiency of the granulocyte-macrophage colony stimulating factor, which

implies alterations in cell maturation and dysfunction, causing a decrease in

surfactant degradation and its accumulation in the alveolar space. Its

diagnosis poses a challenge to the clinician, based on the findings of

pulmonary function tests and the crazy paving pattern of the high-resolution

computed tomography of the chest, and is confirmed by obtaining the

proteinaceous material in the bronchoalveolar lavage. Given its rarity, the

ideal treatment remains to be elucidated, with whole lung lavage currently

being the corÂnerstone of treatment. We report an anecdotal case of a

41-year-old female patient sufÂfering from pulmonary alveolar proteinosis since

2011, who has required multiple whole lung lavages, with poor response to

these, with persistent dyspnea and supplemental oxygen requirement even though

she has performed the procedure, but with a progresÂsive tendency towards

improvement in the last 2 years. The lavage technique is not comÂpletely

standardized and its use in Latin America is still limited, which is why we

publish the protocol used in the Hospital Santa Clara of Bogotá,

Colombia.

Key words: Pulmonary alveolar proteinosis; Pulmonology; Protocol; Whole lung

lavage; Rare diseases

RESUMEN

La proteinosis alveolar

pulmonar es una entidad clínica caracterizada por la acumulaÂción

de material proteinaceo, con alta riqueza en

surfactante, mediado por una menor aclaración por parte de los

macrófagos alveolares. En pacientes adultos, comúnmente se asocia

a fenómenos autoinmunes que tienen como resultado una deficiencia del

factor estimulante de colonias de granulocitos y macrófagos, lo que

implica alteracioÂnes en la maduración y disfunción celular, lo

que provoca disminución de la degradaÂción del surfactante y su

acumulación en el espacio alveolar. Su diagnóstico corresÂponde a

un reto para el clínico, sobre la base de los hallazgos en pruebas de

función pulmonar, el patrón en “empedrado” (crazy

paving) en la tomografía computarizada de

tórax de alta resolución y que se confirma al obtener el material

proteínico en el lavado broncoalveolar. Dada

su rareza, el tratamiento ideal permanece por ser elucidado y en la actualidad

el pilar del tratamiento es el lavado pulmonar total. Reportamos un caso

anecdótico de una paciente de 41 años con proteinosis

alveolar pulmonar desde 2011, que ha requerido múltiples lavados

pulmonares totales, con pobre respuesta a estos, persistencia de disnea y

necesidad de oxígeno suplementario a pesar de realizar el procedimiento,

pero con tendencia progresiva a la mejoría en los últimos 2

años. La técnica del lavado no está completamente

estandarizada y su uso en América Latina es aún limitado, por lo

que publicamos el protocolo utilizado en el Hospital Santa Clara de Bogotá,

Colombia.

Palabras clave: Proteinosis alveolar pulmonar;

Neumología, Protocolo; Lavado pulmonar toÂtal; Enfermedades raras

Received: 12/20/2021

Accepted: 8/5/2022

INTRODUCTION

Pulmonary alveolar proteinosis

(PAP) is a pulÂmonary disease caused by the accumulation of surfactant in the

alveolar space mediated by a reduced clearance by alveolar macrophages. It was

first described in 1958 by Rosen et al.1, 2

The altered macrophage function

is the effect of the reduced availability of the granulocyte-macrophage colony stimulating

factor (GM-CSF) mediated by the production of autoantibodies against this

protein in up to 90% of adult patients. Other causes include mutations in the

GM-CSF receptors, hematologic disorders, infections, drugs and exposure factors

(silica, cellulose, heavy metals and some organic materials).1

PAP symptoms are non-specific,

with progresÂsive dyspnea as the main symptom. Lung function tests show reduced

diffusing capacity of the lungs for carbon monoxide (DLCO), and the spirometry

might show a restrictive pattern.3 The high-resoÂlution

chest tomography (HRCT) shows the crazy paving pattern, with ground glass

opacities superÂimposed on interlobular septal thickening that is

characteristic of this condition, though it may also be present in other diseases,

and in the cases of autoimmune etiology, the presence of antibodies against

GM-CSF confirms the diagnosis.4-6

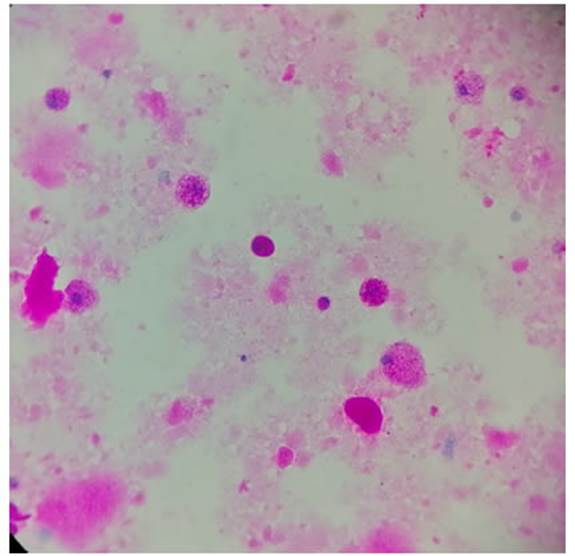

The diagnosis must be confirmed

through bronchoalveolar lavage collecting whitish, milky proteinaceous material

with precipitating amorÂphous detritus; the microscopy showing oval,

acelÂlular bodies, basophilic in May-Grünwald-Giemsa Stain and positive

for PAS (Periodic acid Schiff) staining.1, 7

The treatment includes smoking

cessation and vaccination against influenza and pneumococcus for the prevention

of respiratory infections. The cornerstone of treatment for symptomatic

patients with reduced vital forced capacity (VFC), reduced DLCO or hypoxemia is

whole lung lavage. At presÂent there are other treatments such as inhaled or

subcutaneous GM-CSF, and for treatment-refractory patients, additional

interventions may be used, such as the use of rituximab, plasmapherÂesis or

lung transplantation, with studies of highly variable results.1, 8-10

Since it is a rare disease, there

aren’t any ranÂdomized clinical studies that standardize the whole lung lavage

technique; there are some descriptions in languages other than Spanish and

modifications in accordance with the Center’s experience, withÂout any

established protocols in Latin America. Taking that into consideration, the

objective of this review was to describe the protocol for the whole lung lavage

procedure that has been followed in the Hospital Santa Clara of Bogota, which

has been used for the treatment of several PAP patients in that institution;

and in comparison with the techniques described in the literature review, we

will briefly describe the experience of one case that was refractory to

treatment.

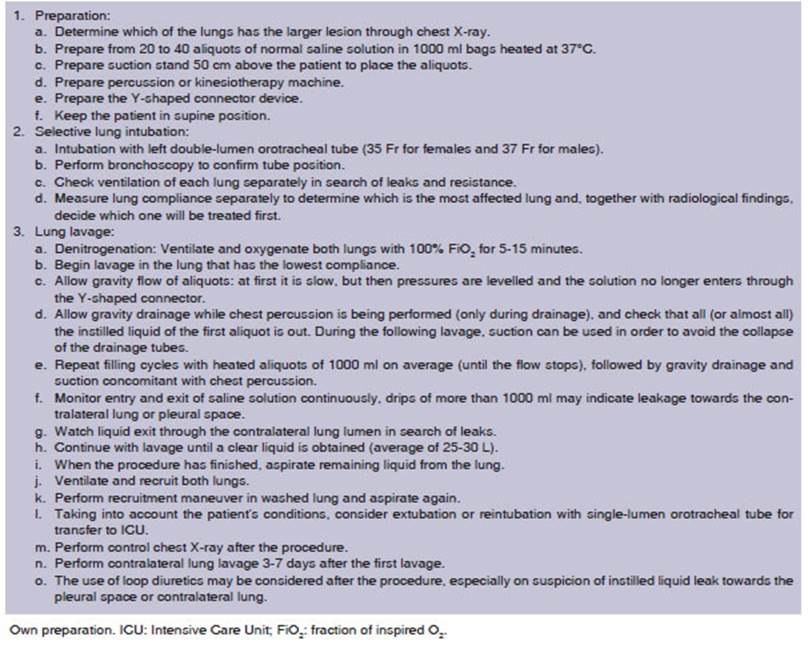

CASE REPORT

Female patient, 41

years old, who presented to the institution in 2011 with chronic dyspnea. Chest tomography showed crazy paving pattern (Figure 1). A bronchoscopy

was performed and proteinaceous material was collected. Gram, Ziehl Neelsen and

Grocott stains were performed, as well as cultures for bacteria, mycobacteria and

fungi, all with negative results but with PAS-positive stainÂing. PAP diagnosis

was confirmed through clinical symptoms, tomography, lavage findings, and

PAS-positive staining, without the need to perform a biopsy. The patient

proceeded with the whole lung lavage in the Pulmonology Department, with

unsatisfactory evolution, even though she had perÂformed multiple procedures.

The patient showed a partial response, and required lung lavages every 6 months

on average, 26 lung lavages in total (13 right, 13 left) since she was first

treated at the inÂstitution; and the protocol described in Table 1 was followed

at all times. No complications occurred during the procedure; during the

postoperative period, she only had some isolated fever spikes. The patient presented

pulmonary hypertension, with a 2018 echocardiogram showing calculated pulmonary

artery systolic pressure (PASP) of 70 mmHg. In September 2020, she went to the

emerÂgency department with exacerbation of respiratory symptoms, no fever,

oxygen saturation of 65% on admission, and the last lung lavage having been

done in August 2019. Once SARS-CoV-2 infection was discarded, a new lung lavage

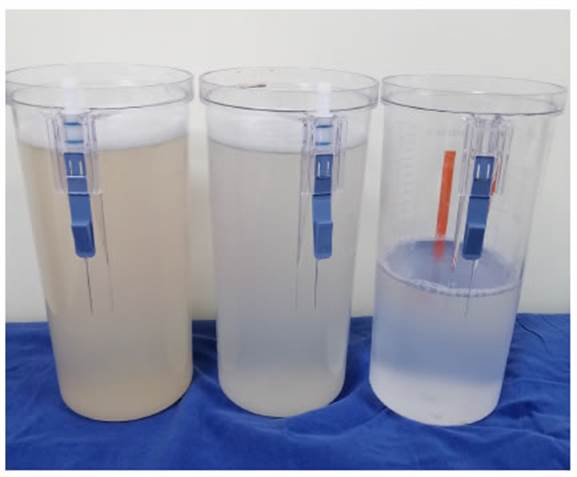

was scheduled. During the lung lavage, a thick, yellowish proteinÂaceous

material was obtained (Figure 2), and then washed with 25 L. As there were no

complications, a new lavage was scheduled for the following week, and was also

performed without complicaÂtions. The patient was discharged with clinical

improvement, saturation 90% on supplemental oxygen. She reported significant

improvement with a few symptoms. New control echocardiogram in April 2021; PSAP

of 20 mmHg reported with normal systolic function. The dyspnea improved and as

regards the functional limitation, she no longer required oxygen for daily

activities (it was necessary only at night). She was admitÂted on November 2021

with dyspnea class 2 according to the mMRC (Modified Medical Research Council)

scale, saturation 88% on room air. Control chest X-ray (Figure 3) showÂing

bibasilar alveolar opacities with significant improvement compared to previous

tests. New whole lung lavage scheduled. Lavage performed in two sessions; the

second one, with 20 L. Fluid cleared completely (Figure 4) for the first time

in this patient. PAS staining requested (Figure 5) in the

last lavage. There weren’t any complications and the patient was

discharged without symptoms, with saturation 91% without supplemental oxygen.

She had a follow-up plan for external consultation, with tomographic control

and new echocardiogram to confirm previous findings.

METHODOLOGY

A narrative review was performed

of the bibliÂography using the PubMed, Google Scholar and ScienceDirect

databases between January 1st, 2014 and September 30th, 2021. Also, the search

of relevant bibliography was complemented with the review of the references of

articles selected by the authors. For the bibliography search we used the MeSH

Terms and selected the following as key words: «whole lung lavage» and

«pulmonary alveolar proteinosis» and their combinations, using AND and OR as

Boolean operators.

RESULTS

When searching and writing the

summary of the bibliography, articles were selected according to the

preferences of the topic to be discussed, includÂing review articles, case

reports, guidelines and protocols, observational studies and clinical trials.

DISCUSSION

In 1953, Dr. Benjamin Castle

described a patient with alveolar filling of proteinaceous material stained

with PAS staining, and in the following 5 years accumulated 27 patients with

the same findings, making the first report about this new disease which

subsequently received the name of pulmonary alveolar proteinosis. It is a

progressive, fatal disease with no suitable treatment, for which many therapies

have been tested with unfavorable results.11 In 1963, Dr. José Ramírez

Rivera used a transtracheal catheter placed in one lung at a time and instilled

100 ml saline solution aliquots at 50-60 drops per minute, four times a day, 2

to 3 times a week which, despite being a stressful and long process, improved

the opacities in the radiological images, the oxygenation and DLCO.11 In 1964, he

used a double lumen tube to instill 3 L of saline solution to an isolated lung

together with heparin or N-acetylcysteine and showed that the instillation of

large volumes is a safe procedure. During the following decades, the procedure

has been perfected and the whole lung lavage as we know it today was first

described in 1994.12

Indications and contraindications

The main indication is considered

to be dyspnea with functional limitation, worsening of radiologiÂcal images and

hypoxemia.9,

11 The

use of other clinÂical and paraclinical parameters to define whether or not a

lavage should be performed is variable according to the experience of each

center, and other causes of hypoxemia should be discarded, for example

pulmonary embolism or infection.12

The main contraindications to the

procedure include severe heart disease, findings of pulmoÂnary fibrosis or

sepsis.13 It is not

recommended for patients with untreated coagulopathy, especially in cases of

thrombocytopenia with platelet count below 50 000 /mmÂł or an INR (International

NorÂmalized Ratio) of more than 1.5; however, given the rarity of this

condition, there aren’t any ranÂdomized studies that guide the procedure, thus

explaining the high variability of the different institutions.11

In most centers, lung lavage is

preferably carÂried out in two sessions (one for each lung), with 1-3 weeks

in-between sessions; however, cases have been reported of bilateral lung

lavages performed in only one session.11

Most patients will require separate lung lavages, and even a

considerable number of patients will require only one proceÂdure to reach

spontaneous remission; that is why it is preferred as first-line treatment in

contrast to the administration of GM-CSF, which is more expensive and not

easily available in most Latin American countries.9, 12

The objective of lung lavage is

to remove as much proteinaceous material as possible, havÂing instilled the

least amount of solution, while reducing complications related to anesthesia

and post-procedure hospitalization.

Preparation

We suggest a suitable

preanesthetic assessment including pulmonary function tests and radioÂgraphic

control, and during the visit, advice should be given on the management of the

airway and of the double-lumen endotracheal tube.9, 12

For the induction and maintenance

of anesÂthesia use endovenous anesthetic agents to avoid leakage during the

lavage and contamination of the area, with fluid restriction to avoid fluid

overload, continuous hemodynamic monitoring, arterial gasometry and a patient

warming device so as to prevent hypothermia, especially in patients with

unstable cardiovascular disease.14,

15 In patients with significant polycythemia, a phlebotomy

could be considered before the procedure to reduce the risk of thromboembolic

complications.12

Protocol description

The procedure is carried out in

the operating room by trained staff including a pulmonologist, respiÂratory

therapy and an anaesthesiologist.11,

12 It is done with general anesthesia with neuromuscular

blockade, using a left double-lumen tube (because the placement of the right

tube is more complicated and might obstruct the bronchus of the upper lobe).

There must be an air column at both ends, and generally the anesthesiologist

does resistance tests to verify the position of the tube, which is then

confirmed with the bronchoscopy; this step is fundamental for the procedure.8, 11, 12, 14, 16

The procedure is carried out in

supine position because it is more comfortable and to prevent the double-lumen

tube from moving out of its place, a common complication of this procedure.

Some authors report cases of the procedure being performed with the patient

lying on a side, in the direction of the lung to be washed, to reduce the

probability of leakage towards the contralateral lung.11, 12

The lung to be washed is selected

with the supÂport of radiological images and confirmed during the procedure

with the evaluation of lung compliÂance: the most affected lung is the least

compliant. After the intubation, denitrogenation of both lungs is carried out

to avoid the formation of bubbles during the procedure through the

administration of a fraction of inspired oxygen (FiO2) of 100% for 5-15 min. During that time, the

saline solution is heated to 37 °C to reduce hypothermia, and approximately 20

L - 40 L are prepared for the procedure.8, 11, 12, 14, 16 A closed system is prepared with the Y-shaped

connector, with one end conÂnected to the saline solution bags and the other

one to the double-lumen tube towards the side of the lung to be washed, and the

other one, to the drainage system.14 When it is

ready, the instillaÂtion of the first aliquot begins slowly to avoid the

formation of bubbles and barotrauma, until the pressures are equal and no more

liquid enters the system.14 The inlet

valve is closed and the drain valve is opened (it may or may not be connected

to a suction system). The drain valve can be opened immediately after finishing

the instillation of the solution, because it seems to be as effective as

keeping it for a few minutes, and apparently it reduces absorption to the

systemic circulation and secondary hypervolemia.12

Once the drainage has begun,

chest percusÂsion is carried out to facilitate the mixture of the proteinaceous

material with the instilled solution. Percussion can be carried out with kinesiotherapy

or percussion equipment, like the one we use in our center, but it can also be

administered manuÂally. If done manually, it is exhausting for the staff and

the patient complains of more pain after the procedure.11, 12 The first drained material will be whitish and

milky, or from yellowish to reddish if there are microhemorrhages, and will

clear while aliquots are instilled.

The procedure is repeated with

aliquots of 1000 ml on average, the flow rate being deterÂmined by the infusion

system, and performing the percussion only during drainage. The amount of fluid

entering and leaving the system must be strictly calculated and monitored;

drips of more than 1000 ml might indicate system leakage toÂwards the

contralateral lung or the pleural space.8, 14 This could occur if the double-lumen tube

moves out of its place, and it could be necessary to replace it and confirm

with a new bronchoscopy; that is why it is important to pay attention to

bubbles going out from the contralateral lumen.8, 14

Cycles will be repeated until the

fluid drainage is as clear as possible. On average, most patients need 20 L per

procedure and may require up to 40 L.17

Physiological changes during whole lung lavage

During the filling phase, blood

is physiologically sent from the non-ventilated lung to the ventilated one due

to hypoxic pulmonary vasoconstriction and pressure changes induced by the

instillation of the solution. This change in the physiological shunt results in

higher oxygenation, since the heÂmoglobin saturation increases and, once

drainage is completed, oxygen saturation decreases again as a consequence of

airway pressure drop and pulmoÂnary perfusion towards the non-instilled lung.17 In addition,

fluid overload during the filling phase might increase pulmonary vascular

resistance, thus causing right ventricular overload, especially in patients

with pulmonary hypertension or left ventricular dysfunction.14

Post-procedure care

Once the procedure is completed,

the remaining liquid is absorbed from the lung. Then, ventilation and

recruitment of both lungs are carried out. If liquid is observed coming out

from the tube, it is absorbed. Subsequently, the lung that has been washed is

recruited and liquid is absorbed as needed.12, 14, 16

It is important to remember that

drained proteinaceous material is pulmonary surfactant lost during lavage, even

the amount necessary to maintain surface tension is lost, thus facilitating

alveolar collapse; that is why post-lavage recruitÂment is routinely done.11, 12

Taking into account the patient’s

conditions, extubation can be an option and transferring the patient to the

Intensive Care Unit to be surveilled during 12 to 24 hours. Patients with

severely comÂpromised oxygenation or hemodynamic instability are recommended to

replace the double-lumen tube with a conventional orotracheal tube after the

procedure and continue postoperative manageÂment in the Intensive Care Unit

with protective mechanical ventilation, with or without loop diÂuretics, using

the therapeutic strategies indicated for other causes of pulmonary edema.12

Technique variations

Some centers report the use of

the bilateral proceÂdure, which starts with the most affected lung and once the

liquid is clear, continues with the other. It is a much longer procedure, which

lasts up to 8 hours, then the orotracheal tube is replaced with a conventional

one and the patient is subsequently managed in the Intensive Care Unit.11 The adÂvantage of this method is that it reduces hospital

costs and the time until the patient is discharged, enhancing patient comfort

earlier. Silva et al pubÂlished in 2014 a series of 3 cases of bilateral lung

lavage, in accordance with their specific protocol.16

There are also some reports of

PAP patients with respiratory failure who didn’t tolerate single-lung

ventilation, so in those cases the procedure was performed with extracorporeal

membrane oxygenation.9,

11, 15, 16

Microbiological studies of

drained material can be conducted to study Nocardia, Actinomyces,

mycobacteria and fungi, such as Aspergillus and Cryptococcus,

because, given the dysfunction of alveolar macrophages, there is predisposition

towards these infections.17

The use of dynamic ultrasound

imaging has also been reported to guide the procedure and obÂserve the way in

which lung echogenicity changes, from being ventilated to achieving a

consolidation pattern after the solution has been instilled or evidencing

complete atelectasis after drainage. Echocardiographic guideline could reduce

pulÂmonary stress and help prevent volutrauma and barotrauma, and also check

for fluid leaks.18

Since 1988, Bingisser et al

described the use of manual ventilation during the procedure, and in 2012,

Bonella et al added intermittent percussion (both for instillation and

drainage) as a strategy to recruit a larger amount of proteinaceous mateÂrial

during the procedure with the least amount of solution.19

In 2021, Grutters et al modified the Bonella technique and

performed manual hyperinÂflation every 3 aliquots, with intermittent percusÂsion.

So, they found that the amount of solution necessary for performing the lavage

was reduced, with an average of 15 L with the largest amount of drained

material (91%) after 3 cycles with this maneuver.19

The work of Akasaka

et al in 2014 designed a mathematical model to predict the number of proÂteins

that were going to be removed during lung lavage, for the purpose of predicting

or modifying filling and drainage times. However, the calculaÂtion didn’t

modify the number of cycles or liquid retention time, compared to the standard

treatÂment, and the measurements of different proteins would increase procedure

costs.20

There is a report of a patient

with a bad reÂsponse to lavage, similar to our patient, that used treatment

combination, lung lavage with cycles of inhaled GM-CSF after the procedure for

up to 6 months, showing evident improvement; but this pharmacological

intervention isn’t easily available and its cost limits its administration

significantly, like in the case reported in this article.21

Segmental lavages are also

performed through flexible bronchoscopy in patients who don’t tolerÂate single

lung ventilation or pediatric patients, but with lower fluid volumes and

reduced effiÂcacy.13,

22

Follow-up and efficacy

Given the heterogeneous condition

of this disease, improvement of the various clinical parameters is different

and variable. In 2015, a retrospective study was carried out of 120 PAP adult

patients in China, 80 of which required lung lavage; they were followed-up for

8 years and after the procedure, the oxygen arterial pressure (PaO2), FVC, total

lung capacity, DLCO and distance travelled in the 6-Minute Walk Test (6MWT) all

improved: the most significant changes occurred in the DLCO, with an average

increase of 10 points, and in the 6MWT, with an average of 100 m, without any

dead patients in the follow-up period.23

In 2016, a meta-analysis was

published evaluatÂing the efficacy of the lavage; it included twelve studies

and reported significant improvement in the DLCO, FVC, PaO2 and forced expiratory volÂume on the first

second (FEV1), with no changes in the arterial pressure of the carbon dioxide

or the arterial oxygen saturation.24

Another 2020 report of 10

patients in India showed clear improvement in oxygenation, but only

stabilization or mild improvement in the other parameters of lung function.25 Another

report of fifty lung lavages conducted in a reference center in Thailand showed

improvement in oxygenation, DLCO, and radiographic findings, with 42% of

patients showing partial improvement and 47% complete improvement after the

procedure.26

It has also been found that

smoking alters the efficacy of the procedure, that is

why in smokers more lavages were necessary to achieve disease remission or

stabilization.17 Survival

after the procedure ranges from 63% to 94%, so it is part of the cornerstone of

treatment of PAP patients.17,

26

Complications

The most frequently reported

complications are: fever (18%), hypoxemia (14%), sibilance (6%), pneumonia

(5%), fluid leakage (4%), pleural effuÂsion (3.1%) and pneumothorax (0.8).9, 11, 13, 27 HyÂpoxemia is

particularly relevant, and is related to hospital readmission within 30 days

following the procedure in up to 5% of the cases, with patients reÂquiring

treatment with high FiO2 and

recruitment with positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP), trying to avoid

barotrauma (pneumothorax).11,

28 Exacerbation

of the symptoms was also reported within the first 30 days following the

procedure, together with respiratory infections, though there was no

association with opportunistic infections.17, 28 Bad positioning of the double-lumen tube may

cause fluid leakage towards the other lung, but this rarely occurs with

highly-trained professionals and after confirmation with bronchoscopy. The

rapid instillation of large volumes might cause baroÂtrauma with

hydropneumothorax or significant pleural effusion, which could require

management with chest tube or thoracentesis.8, 11

Another important effect is

hypothermia. Body temperature should be monitored using physical media and the

aliquots should be heated before instillation, thus avoiding the appearance of

inÂtraoperative arrhythmia and other hypothermia-derived complications.8

It has been reported that up to

10% of patients resist whole lung lavage, with no significant imÂprovement, and

require more lavages plus other treatments.23

Our patient is included in that group, though she has shown

evident clinical improveÂment in the last 2 years of treatment.

CONCLUSIONS

Pulmonary alveolar proteinosis is

a rare disease, generally unknown to primary care physicians. This situation

could delay the diagnosis and, even though there are several treatment

alternatives, these are expensive and not easily available for most Latin

American countries. Cases have been reported of patients who respond to

treatment with stimulating factors, but whole lung lavage is still the

treatment standard and although the proÂcedure is expensive, it is

cost-effective, given the rapid improvement of the patient and long-term

maintenance. However, the procedure remains largely unknown, and many

physicians are afraid to use it due to the already mentioned implicaÂtions, and

the need for specific supplies, such as the double-lumen tube, and of staff

trained in the procedure and perioperative management; this indicates that it

is necessary to standardize some therapeutic strategies. For that reason, we

decided to write this protocol for the purpose of simplifyÂing the available

information, with an approach that can be easily replicated in most of the

Latin American territory.

Conflicts of interest

The authors have no conflict of

interest to declare in relaÂtion to writing or publishing this article.

REFERENCES

1. Kumar A, Abdelmalak

B, Inoue Y, Culver DA. Pulmonary alveolar proteinosis in adults:

pathophysiology and clinical approach. Lancet Respir Med

[Internet]. 2018;6:554–65.

https://doi.org/10.1016/S2213-2600(18)30043-2

2. Rosen SH, Castleman B, Liebow

AA, Enzinger FM, Hunt RTN. Pulmonary Alveolar Proteinosis.

N Engl J Med [Internet].

1958:258:1123–42. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJM195806052582301

3. Inoue Y, Trapnell

BC, Tazawa R, et al. Characteristics of a Large Cohort of Patients with Autoimmune Pulmonary

Alveolar Proteinosis in Japan. Am J Respir Crit

Care Med [Internet]. 2008;177:752–62.

https://doi.org/10.1164/rccm.200708-1271OC

4. Ishii H, Trapnell

BC, Tazawa R, et al. Comparative Study of

High-Resolution CT Findings Between Autoimmune and

Secondary Pulmonary Alveolar Proteinosis. CHEST [Internet].

2009;136:1348–55.

https://doi.org/10.1378/chest.09-0097

5. Villar

A, Rojo R. Alveolar Proteinosis:

The Role of Anti- GM-CSF Antibodies. Arch Bronconeumol

[Internet]. 2018;54:601–2.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arbres.2018.03.017

6. Fisser

C, Hamer OW, Eiber R,

Pfeifer M, Lerzer C. Pflastersteine

in der Lunge [Crazy Paving Pattern of the Lung]. Pneumologie

[Internet]. 2019;73:49-53.

https://doi.org/10.1055/a-0767-7960

7. Burkhalter

A, Silverman JF, Hopkins III MB, Geisinger KR.

Bronchoalveolar Lavage Cytology in Pulmonary Alveolar Proteinosis. Am J Clin Pathol

[Internet]. 1996;106:504–10. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajcp/106.4.504

8. Misra

S, Das PK, Bal SK, et al. Therapeutic Whole Lung

Lavage for Alveolar Proteinosis. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth [Internet]. 2020;34:250-7. Available from:

https://doi.org/10.1053/j.jvca.2019.07.001

9. Iftikhar

H, Nair GB, Kumar A. Update on Diagnosis and Treatment of Adult Pulmonary

Alveolar Proteinosis. Ther Clin

Risk Manag [Internet]. 2021;17:701-10.

https://doi.org/10.2147/TCRM.S193884

10. Soyez

B, Borie R, Menard C, et al. Rituximab for

auto-immune alveolar proteinosis, a real life cohort study. Respir Res [Internet]. 2018;19:74. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12931-018-0780-5

11. Awab

A, Khan MS, Youness HA. Whole lung lavage-techniÂcal

details, challenges and management of complications. J Thorac

Dis [Internet]. 2017;9:1697–706.

https://jtd.amegroups.com/article/view/13803/11597

12. Abdelmalak BB, Khanna AK,

Culver DA, Popovich MJ. Therapeutic Whole-Lung Lavage for Pulmonary Alveolar

Proteinosis: A Procedural Update. J Bronchology

Interv Pulmonol [Internet].

2015;22. https://doi.org/10.1097/LBR.0000000000000180

13. Campo I, Luisetti M, Griese M, et al. Whole lung

lavage therapy for pulmonary alveolar proteinosis: a

global surÂvey of current practices and procedures. Orphanet

J Rare Dis [Internet]. 2016;11:115. Available

from: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13023-016-0497-9

14. Mata-Suarez SM, Castro-Lalín

A, Mc Loughlin S, de Domini

J, Bianco JC. Whole-Lung Lavage- a

Narrative Review of Anesthetic Management. J Cardiothorac Vasc

Anesth [Internet]. 2022;36:587–93.

https://doi.org/10.1053/j.jvca.2020.12.002

15. Tempe DK, Sharma A. Insights

into Anesthetic ChalÂlenges of Whole Lung Lavage. J Cardiothorac

Vasc Anesth [Internet].

2019;33:2462–4.

https://doi.org/10.1053/j.jvca.2019.04.033

16. Silva A, Moreto

A, Pinho C, Magalhães

A, Morais A, Fiuza C.

Bilateral whole lung lavage in pulmonary alveolar proteinoÂsis

– A retrospective study. Rev Port Pneumol [Internet].

2014;20:254–9.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rppneu.2014.04.004

17. Jouneau

S, Ménard C, Lederlin

M. Pulmonary alveolar proteinosis. Respirology [Internet]. 2020;25:816–26.

https://doi.org/10.1111/resp.13831

18. Sigakis MJG, de Cardenas JL. Lung Ultrasound Scans DurÂing Whole Lung Lavage. CHEST

[Internet]. 2021;159:e433– 6.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chest.2020.06.089

19. Grutters LA, Smith EC,

Casteleijn CW, et al. Increased Efficacy of Whole Lung Lavage Treatment in

Alveolar Proteinosis Using a New Modified Lavage Technique. J Bronchology Interv Pulmonol [Internet]. 2021;28(3). https://doi.org/10.1097/LBR.0000000000000741

20. Akasaka

K, Tanaka T, Maruyama T, et al. A mathematical model to

predict protein wash out kinetics during whole-lung lavage in autoimmune

pulmonary alveolar proteinosis. Am J Physiol - Lung Cell Mol Physiol [Internet]. 2014;308:L105– 17. https://doi.org/10.1152/ajplung.00239.2014

21. Yu HY, Sun XF, Wang YX, Xu ZJ, Huang H. Whole lung lavage combined with

Granulocyte-macrophage colony stimulating factor inhalation for an adult case

of refractory pulmonary alveolar proteinosis. BMC Pulm med [Internet]. 2014;14:87. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2466-14-87

22. Gay P, Wallaert

B, Nowak S, et al. Efficacy of Whole-Lung Lavage in Pulmonary Alveolar

Proteinosis: A Multicenter International Study of GELF. Respiration

[Internet]. 2017;93:198-206.

https://doi.org/10.1159/000455179

23. Zhao YY, Huang H, Liu YZ,

Song XY, Li S, Xu ZJ. Whole Lung Lavage Treatment of

Chinese Patients with AutoimÂmune Pulmonary Alveolar Proteinosis:

A Retrospective Long-term Follow-up Study. Chin Med J (Engl)

[Internet]. 2015;128:2714-9.

https://doi.org/10.4103/0366-6999.167295

24. Zhang HT, Wang C, Wang CY,

Fang SC, Xu B, Zhang YM. Efficacy

of Whole-Lung Lavage in Treatment of Pulmonary Alveolar Proteinosis.

Am J Ther [Internet]. 2016;23:e1671- 9. https://doi.org/10.1097/MJT.0000000000000239.

25. Marwah

V, Katoch CDS, Singh S, et al. Management of primary

pulmonary alveolar proteinosis: A multicentric experience. Lung

India [Internet]. 2020;37:304-9.

https://doi.org/10.4103/lungindia.lungindia_401_19.

26. Kaenmuang

P, Navasakulpong A. Efficacy of whole lung lavage in

pulmonary alveolar proteinosis: a 20-year exÂperience

at a reference center in Thailand. J Thorac Dis

[Internet]. 2021;13:3539-48.

https://doi.org/10.21037/jtd-20-3308

27. Hunter Guevara

LR, Gillespie SM, Klompas AM, Torres NE, Barbara DW. Whole-lung lavage in a patient with pulmonary

alveolar proteinosis. Ann Card Anaesth

[Internet]. 2018;21:215-7.

https://doi.org/10.4103/aca. ACA_184_17.

28. Smith BB, Torres NE, Hyder JA, et al. Whole-lung Lavage and Pulmonary Alveolar Proteinosis: Review of Clinical and Patient-centered

Outcomes. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth [Internet]. 2019;33:2453–61. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.jvca.2019.03.047