Autor : Esquivel Florencia1, Costantini Andrea2, Maspero Jorge3, SimĂłn Gonzalo2, Moorat Anne, Mallett Steve

1Laboratorios Phoenix SAICF 2 GlaxoSmithKline Argentina 3CIDEA Argentina

https://doi.org./10.56538/ramr.ABRV4728

Correspondencia : Florencia Esquivel E-mail: floresqui07@yahoo.com.ar

ABSTRACT

Asthma is a serious worldwide health

problem. According to the last report of the MinÂistry of Health, 1,380,000

subjects suffer from asthma in Argentina. The International Guidelines (Europe,

United States, WHO [World Health Organization]) have varying approaches to

define equivalence considerations and the possibility of switching orally

inhaled products. Whereas an in vitro approach is possible, in general

the Guidelines recommend providing more clinical evidence that supports the

possibility of switching from the innovative product to another one

subsequently developed with the same acÂtive principles in the form of dry

powder inhaler. This randomized, phase IV study has been conducted to establish

the efficacy, safety and tolerability of Neumoterol®

400 compared to the reference medicinal product Symbicort

forte, budenoside/formoterol

fumarate 320/9 μg twice daily in asthmatic patients. Also, the patients’ preference on

the use of the devices has been evaluated.

The evaluated formulation has

proven to be non-inferior compared to the reference medicinal product. The

lower limit of the 95% CI (confidence interval) for the treatÂment difference

was greater than the prespecified non-inferiority

margin of –125 mL (difference: 0.044 l [95% CI: –0.008 to 0.096]). Also, higher

values were evidenced for the AUC0-10h

(area under the curve) of the FEV1 (forced

expiratory volume in the first second) and a more important change of the

baseline score in the asthma control test on day 29 for the budenoside/formoterol fumarate capsules of

400/12 μg. In one exploratory

test about the patients’ preference on the use of the devices, a higher proÂportion

of participants expressed their global preference for the budenoside/formoterol fumarate capsule of

400/12 μg. No differences

were reported in the incidence of AEs (adverse events) or SAEs (serious adverse

events) during or after the treatment. The safety profile of both products in

general coincides with the verified profile of budenoÂside/formoterol fumarate.

Key words: Asthma; Budenoside; Formoterol

fumarate; Inhalation device.

RESUMEN

El asma es un grave problema de salud mundial.

Según el último informe del Ministerio de Salud, 1 380 000

sujetos padecen asma en la Argentina. Las guías internacionales (Europa,

Estados Unidos, OMS) varían en su enfoque para definir la equivalencia y

la posibilidad de intercambio de los productos para inhalación

respiratorios. Si bien es posible un enfoque in vitro, en general las

guías recomiendan brindar más indiÂcios clínicos que avalen

la posibilidad de intercambiar el producto innovador por otro posteriormente

desarrollado con iguales principios activos en polvo seco para inhalar. Este

estudio, aleatorizado de fase IV, se realizó para establecer la

eficacia, seguridad y tolerabilidad de Neumoterol® 400 en

comparación con el producto medicinal de refeÂrencia Symbicort

forte budesonida/fumarato de formoterol 320/9 μg, indicados 2 veces al día en pacientes

asmáticos. Además, se evaluó la preferencia de los

pacientes por uno u otro dispositivo.

Se demostró la no inferioridad de la

formulación evaluada en comparación con el proÂducto medicinal de

referencia. El límite inferior del IC del 95 % para la diferencia entre los

tratamientos fue mayor que el margen predefinido de no inferioridad de –125 mL (diferencia: 0,044 l [IC del 95 %: –0,008 a 0,096]).

Asimismo, se comprobaron valores más altos para el AUC0-10h del FEV1 y un mayor cambio respecto del puntaje basal

en la prueba de control del asma el día 29 para las cápsulas de budesonida/fumarato de formoterol 400/12 μg. En un

análisis exploratorio sobre la preferencia de los pacientes por los

dispositivos, una mayor proporción de participantes expresaron su

preferencia global por la cápsula de budesonida/fumarato de formoterol 400/12 μg. No se informaÂron diferencias en la incidencia de

AE o SAE graves durante el tratamiento o después de este. El perfil de

seguridad de ambos productos en general concordó con el perfil comprobado

de budesonida/fumarato de formoterol.

Palabras clave: Asma; Budesonida; Fumarato

de formoterol; Dispositivo inhalatorio

Recibido: 06/05/2021

Aceptado: 10/03/2022

INTRODUCTION

Asthma is a chronic inflammatory disorder

of the airways, characterized by hyperreactivity of

the airway that produces recurring episodes of sibiÂlance, shortness of breath

and cough, especially at night or early in the morning. It is a high-prevalence

disease and represents an important public health problem.1, 2

The guidelines of the Global

Initiative for Asthma (GINA) highlight the need to treat the inflammation of

the airways in asthma, and also to acknowledge the importance of prophylactic

inhaled drugs, such as inhaled corticosteroids (ICS) and the combinations of

ICS/βlong-acting

beta-adrenergic agonists (LABA) (also called long-acting β-2 agonists), like the product containing the budenoside/formoterol fumarate combination (BFF).2

Symbicort forte® (with turbuhaler® inhaler) was

authorized in 2010 in Argentina for the treatment of asthma and chronic

obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD).3

Phoenix laboratory developed Neumoterol®

400, a combination of a fixed-dose of BFF dry powder (DPI), in

capsules, to be administered by means of a single-dose inhaler provided by the Plastiape Company. This formulation consists of a capsule

containing a small amount of powder with a mixÂture of 400 μg of micronized budenoside,

12 μg of micronized formoterol fumarate and

excipients. It is indicated as maintenance therapy against asthÂma and to treat

patients suffering from COPD. The International Guidelines from Europe, the

United States and the WHO, for example, have varying approaches regarding

equivalence considerations and the possibility of switching orally inhaled

products. Whereas an in vitro approach is possible, in general the

Guidelines recommend providing more clinical evidence that supports the

possibilÂity of switching between different formulations of the same active

principles. However, in areas with emerging markets, the regulatory approach of

providing commercial licensing for respiratory inhalers is generally based on

the establishment of pharmaceutical equivalence only through an in vitro analysis.

In the case of Argentina, the BFF capsule (Neumoterol® 400) was

approved only basing on in vitro evidence.

This phase IV study was conducted

to show the non-inferiority (primary objective), and gather scientific evidence

about the efficacy, safety and tolerability, and also to show the patients’

preferÂence for the BFF 400/12 μg capsule (Neumoterol®) in comparison with the reference

medicinal prodÂuct (RMP) BFF 320/9 μg (Symbicort forte®) in asthmatic patients.

METHODS

Study design

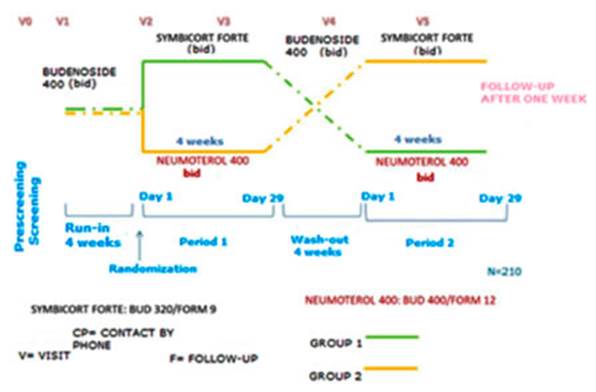

A phase IV, multicentric,

open, randomized, douÂble-crossover, non-inferiority study to compare the

efficacy, safety and tolerability of Neumoterol® 400 (BFF

400/12 μg) administered

through its specific inhaler, and the RMP, Symbicort

forte® (BFF

320/9 μg) administered

through the turbuhaler® device in adult asthmatics. (Figure 1)

The study was carried out in

accordance with the Good Clinical Practice (GCP) and the InterÂnational Council

for Harmonization (ICH) and all current requirements related to subjects’

confidenÂtiality, apart from the ethical principles detailed in the Declaration

of Helsinki of 2008. We obtained written informed consent of each subject

before specific study procedures were performed.

The study was divided in six

phases: prescreenÂing, screening/run-in (4 weeks), treatment period 1 (4

weeks), washout (at least, 4 weeks), treatment period 2 (4 weeks) and follow-up

(1 week). The total duration for each subject was at least 17 weeks. The

schedule included up to six visits and one follow-up phone call.

At the prescreening visit,

informed consent was obtained before performing any procedure or making changes

in the dosing regimen of each participant. During prescreening, patients were

instructed about the screening and run-in visit. During visit 1 (screening and

run-in), subjects who met the inclusion criteria began a run-in period of 4

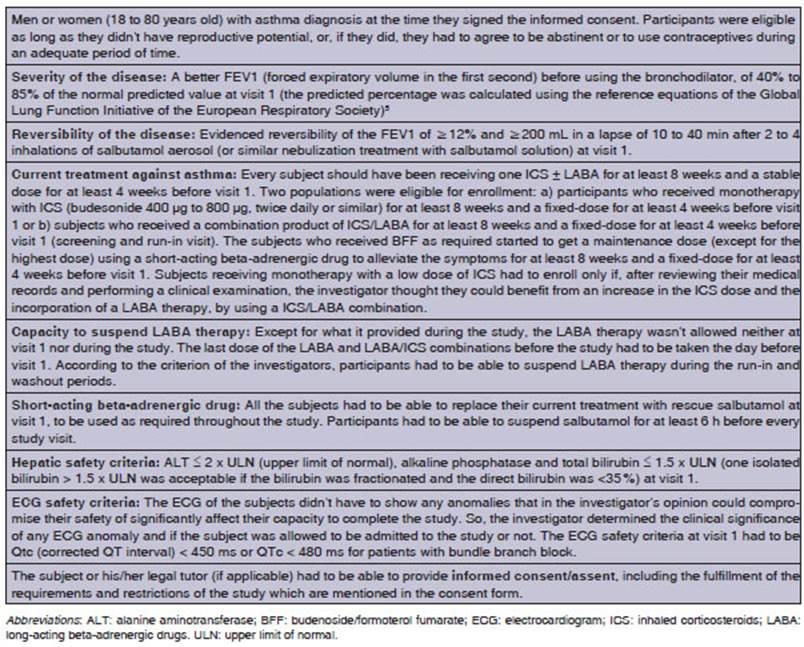

weeks. Tables 1 and 2 provide information about inclusion and exclusion

criteria.

During both the run-in and

washout periods, all the subjects received 400 μg of budenoside as DPI,

twice a day. All the participants were allowed to use rescue medication

(pressurized metered-dose inhaler of salbutamol 100 μg) during the course of the study, until visit 5.

At the end of the run-in period,

the patients were re-evaluated; each subject was told to self-administer the

study medication in each treatÂment period during 4 weeks, in the following

way, taking into account the randomization schedule:

a) inhalation of one capsule of Neumoterol® 400 (BFF

400/12 μg) through his/her

device twice daily, one capsule in the morning and the other one in the

evening/night (approximately 12 hours later); b) inhalation of RMP through turbuhaler® (BFF 320/9 μg) twice daily, in the morning and in the evening

(approximately 12 hours later). After the washout phase of 4 weeks, the

participants began the alternative treatment according to the randomÂization

schedule. The following procedures were carried out: efficacy tests, pharmacodynamic (PD) analyses, patient preference survey on

the use of the devices, and safety evaluations.

To participate in the study,

eligible subjects were required to show a better forced expiratory volume in

the first second (FEV1)

before the use of the bronchodilator between ≥ 40% and ≤ 85% of the

normal predicted value during visit 1 (screening and run-in visit). The

predicted percentage was calculated using the reference equations of the Global

Lung Function Initiative of the European Respiratory Society5

and applying equations or race adjustments, as appropriate.

Disease reversÂibility was evidenced with the improvement in the FEV1 (≥ 12%

and ≥ 200 mL) in a lapse of 10 to 40 min after 2 to 4 inhalations of

salbutamol as aerosol inhaler (or similar nebulization treatment with

salbutamol solution). Also, the FEV1

stability limit was considered as a reference point of the

subjects’ asthma status at run-in, and was used for the comparison throughout

the whole treatÂment phase to evaluate the safety of the subject. It was

calculated at visit 2 as 75% of the best FEV1 before salbutamol.

Patients were dismissed from the

study if they missed a required visit, if they didn’t show up for a re-scheduled visit or weren’t able to contact the clinic

to re-schedule the missed visit. If the particiÂpant couldn’t be contacted, the

case was considered as withdrawal by subject for a primary reason, “lost to

follow-up”. Furthermore, subjects were dismissed from the study if some of the

following criteria were met after taking into account the mean duration of the QTc of electrocardiograms in triplicate: a) QTc > 500 ms; b) QT (not

corrected) > 600 ms; c) increase of at least 60 ms compared to baseline QTc.

No privileges or

protocol exemptions were alÂlowed, except for immediate safety concerns.

Compliance: The subjects received study treatÂment at home, except

for the morning doses of visÂits 2 to 5, which they received at the clinic and

were observed by the study staff to ensure an adequate administration. Patient

compliance was evaluated during clinical visits 3 and 5 and in case of early

discontinuation by reviewing the dose counter of the

RMP device and counting unused capsules. If the compliance rate was lower than

80% or higher than 120%, the patient was re-educated about the indicated dose.

If the treatment was suspended prematurely during the course of the study or

the compliance was outside the acceptable range, the Center monitor would be

contacted for the purpose of analyzing the subject’s eligibility to continue

his/her participation in the study.

Patient compliance

was also evaluated through a phone call at the end of the second week of each

treatment period. The Center physician/staff had shown each subject the

procedure for reading the devices accurately before the beginning of the study.

Endpoints: The primary efficacy endpoint was the change in trough

FEV1 in the morning of day 29 in comparison with the baseline value. Trough

FEV1 was defined as the morning prebronchodilaÂtor

and pre-dose value, 12 hours after last evening dose (day 28), at the end of

each treatment period.

The secondary

efficacy endpoints included the area under the curve (AUC) of the FEV1 of 0-10

h at the beginning of each treatment period (0 [beÂfore the dose], 5 min, 15

min, 30 min; 1, 2, 5 and 10 h after the morning dose on day 1) and the change

in the asthma control test (ACT) score6 compared to the baseline

value after 4 weeks of each treatment period. The equipment used to obtain spirometry measurements either met the minimum performance

recommendations of the American Thoracic Society7 or exceeded them.

All the centers used their own spirometry equipment.

The highest FEV1 was recorded after three acceptable efforts. In order to

determine the AUC0-10h, the FEV1 was measured during clinical visits 2 and 4,

at 0 (before dose), 5, 10 and 20 min; and 1, 2, 5 and 10 h after the morning

dose. The ACT was an autocomplete questionnaire of 5 items which has been

developed to measure the subject’s asthma control. It could be quickly and

easily completed at the clinical practice.6

The subject’s

preference on the use of the deÂvices at the end of each treatment period was

deÂfined as an exploratory endpoint. Such preference was analyzed by means of a

questionnaire. During visit 3, the participants were asked to complete a survey

with 3 questions; during visit 5 (end of study), they

completed a survey with 4 questions.

Safety endpoints

included the change in vital signs (pulse and arterial pressure) compared to

the baseline value, the electrocardiogram and clinical biochemistry tests, the

incidence of adverse events (AEs) during each treatment period, the incidence

of asthma exacerbations (defined as worsening of asthma that requires treatment

other than the treatment of the study or rescue salbutamol; it could even

require the use of inhaled or systemic corticosteroids, a visit to the

emergency department or hospitalization), the incidence of serious asthma

exacerbations (defined as worsening of asthma that requires systemic corticosteroids

during at least 3 days, or hospitalization or a visit to the emergency

department), the incidence of oral candidiasis evaluated through tests and

early discontinuÂation.

Statistical analysis:

Sample size calculations were based on the

primary efficacy endpoint. Variability calculations were based on a previous

study8 in which the observed within-subject stanÂdard deviation was

210 mL. Assuming said value, 168 subjects would be

necessary to show the non-inferiority of the Neumoterol®

400 inhaler (BFF 400/12 μg) and RMP with BFF 320/9 μg twice

daily in asthmatic adults, taking into account a true difÂference of –50 mL

with 90% power and a one-sided significance level of 2. 5%.

The non-inferiority

margin was set at –125 mL according to the minimal clinically important difÂferences

(MCIDs) for this population of patients. It has been shown before that MCIDs for a range of asthmatic patients were 230 mL.9

In order to consider a withdrawal rate of approximately 10%, the planned number

of subjects to be randomized was 187 participants. Around 234 subjects had to

be selected and a failure rate of 20% was expected in order to reach 187

randomized subjects and to have 168 subjects completing the study.

An intention-to-treat

(ITT) analysis was used for the primary efficacy analysis. A back-up efficacy

analysis was carried out using the per-protocol population (PP). Safety

analyses were conducted with the safety population. No interim analysis was

planned for this study.

The primary efficacy

analysis was conducted with a mixed effects analysis of covariance, with the

baseline FEV1, treatment group and period as fixed effects, and the subject as

random coefficient. The non-inferiority was evaluated by examining the lower

limit of the confidence interval (one-sided significance level of 0.025) and

comparing it with the non-inferiority margin of –125 mL.

For the secondary endpoints, other comparisons were made between the product of

the study (BFF 400/12 μg) administered through a capsule inhaler and the RMP

(BFF 320/9 μg). Such comparisons were considered as backup, and no

multiplicity adjustments were applied. Current versions of the SAS software

were used.

RESULTS

Baseline data

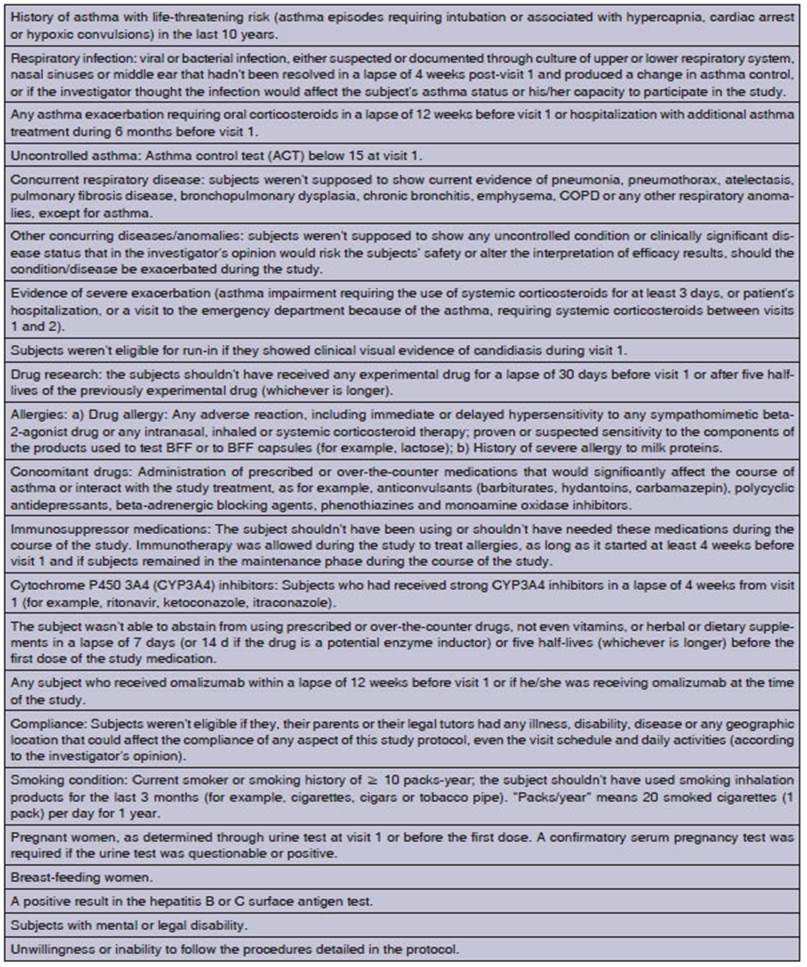

A total of 239 subjects

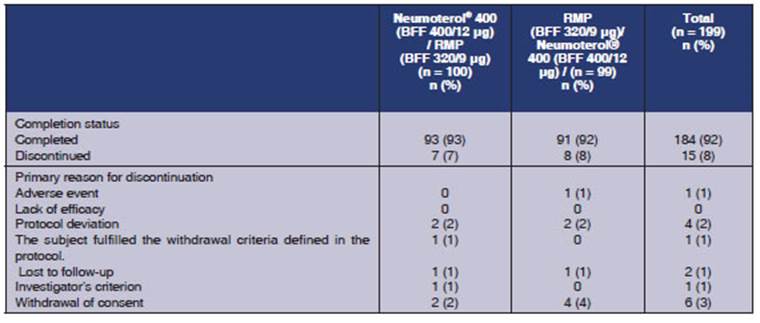

were enrolled in the study, and 199 were randomized (Figure 2). 184 (92%) of

the randomized subjects completed the study and 15 (8%) withdrawn from the

study. Common reasons for suspension were withdrawal of conÂsent (n = 6;

3%) and protocol deviations (n = 4; 2%). There weren’t any withdrawals

for lack of efficacy. Table 3 summarizes the distribution of the study subjects

according to each treatment period.

All the randomized

subjects were included in the safety and ITT population (n = 199) and 158 subÂjects

(79%) were included in the PP population.

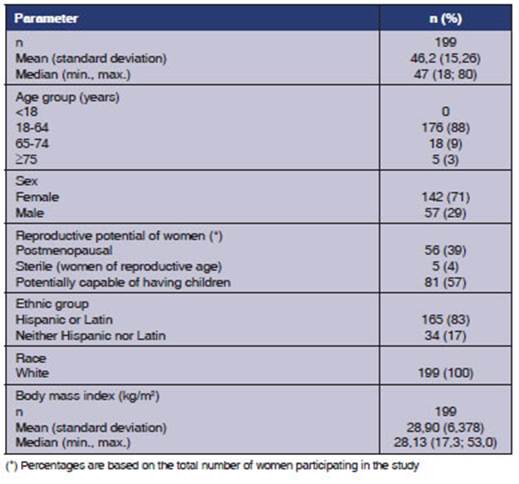

The demographic

characteristics include both groups due to the crossover design of the study.

The participants' median of age was 47 years, and most subjects were women

(71%). Table 4 shows a complete description of baseline characteristics.

At the screening

visit, the mean FEV1 before the bronchodilator was 1.922 L (66.31% of the

normal predicted value) and the mean FEV1 after the bronchodilator was 2.393 L

(82.56% of the normal predicted value). The mean reversibility of the FEV1 was 470.60 mL (25.38%).

Cardiovascular risk

factors were reported in 49 subjects (25%), including hypertension (n =

43; 22%), hyperlipidemia (n = 10; 5%) and diabetes (n = 9; 5%).

During the study, 106 participants (53%) received one concomitant drug or more.

Analgesics, antihypertensives and antihistaminics

were the most frequently prescribed drugs.

Treatment compliance

was at least 80% for most participants (188/191 subjects [98.4%] for the Neumoterol® 400 capsule and 183/187

subjects [97.8%] for the RMP). The median of compliance was within the 94%-97%

range for both formulaÂtions during each treatment period.

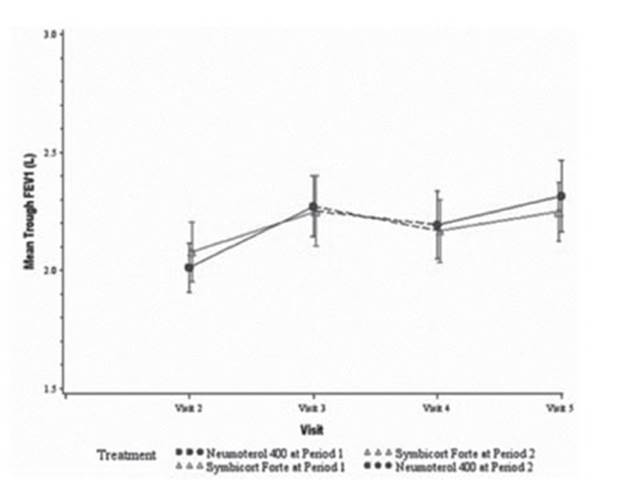

Efficacy results: The primary efficacy endpoint was the change in trough

FEV1 in the morning of day

29, compared to the baseline value. In both treatments, there was an increase

in the morning trough FEV1 in

the ITT population. The mean increase in the least squares (LS) adjusted to the

model was 0.194L for Neumoterol® 400 and 0.150 L for the RMP.

The non-inferiority of the Neumoterol® 400 capsule (BFF 400/12 μg) was

demonstrated: the lower limit of the 95% confiÂdence interval (CI) for the

treatment difference was higher than the predetermined non-inferiority margin

of –125 mL (difference of 0.044 L; 95% CI: –0.008; 0.096) (Figure 3).

One analysis carried

out in the PP populaÂtion was similar to the primary analysis of the ITT

population. The non-inferiority of the Neumoterol®

400 capsule (BFF 400/12 μg) was evidenced when compared with the RMP (BFF 320/9

μg) (treatment difference: 0.043 l; 95% CI: –0.012;

0.098).

There was an

improvement in trough FEV1 in

both treatments from the baseline period until day 29 of period 1 (from visit 2

to visit 3) and from the baseline period until day 29 of period 2 (from visit 4

to visit 5). Whereas the trough FEV1 decreased

during the washout period of 4 weeks between peÂriods 1 and 2, it remained

above the baseline value before treatment (that is to say, the mean trough FEV1 in the baseline period for

period 2 [visit 4] was barely higher than the level observed during the

baseline period for period 1 [visit 2], regardless of the treatment).

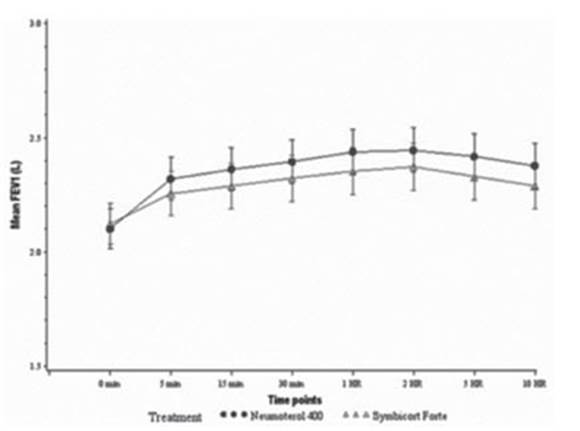

The AUC0-10 h of the FEV1 at the beginning of each treatment

period was a secondary efficacy endpoint. In the ITT population, the AUC0-10 h of the FEV1 on day 1 was 0.98 L*h (95%

CI: 0.576; 1.384) higher for Neumoterol®

400 (BFF 400/12 μg) (Figure 4).

In the ITT

population, both treatments were associated with an increase in the ACT score

(another secondary efficacy endpoint) from the baseline period until day 29.

The mean increase in the LS adjusted to the model was 1.6 points for Neumoterol® 400 (BFF 400/12 μg) and

1.0 point for RMP (BFF 320/9 μg). This treatment difference favored the BFF 400/12 μg

capsule, since there was a difference of 0.6 points (95% CI: 0.1; 1.1).

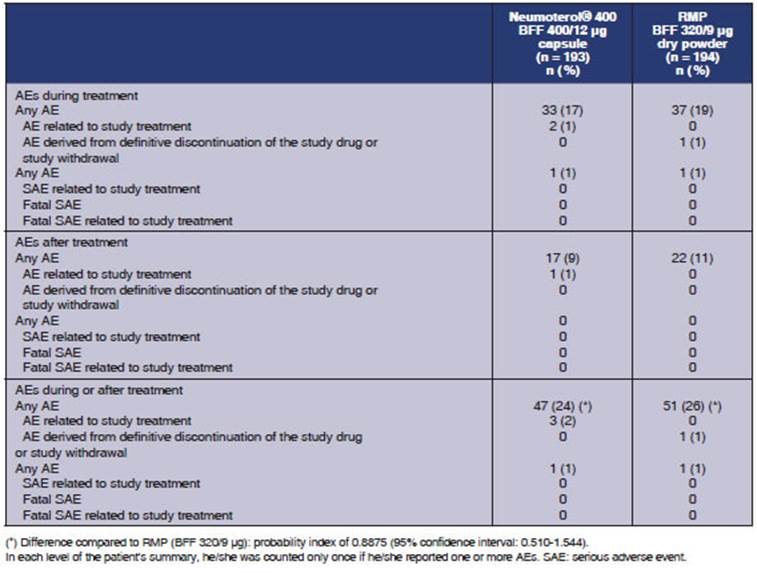

Safety results: AEs were reported during treatÂment in 33 patients

(17%) of the group receiving the BFF 400/12 μg capsule

and 37 subjects (19%) of the group who received BFF 320/9 μg.

Post-treatment AEs were reported in 17 (9%) and 22 (11%) participants,

respectively. AEs (either during or after treatment) were reported in 47

subjects (24%) for the BFF 400/12 μg capsule and 51 paÂtients (26%) for BFF 320/9 μg. There

wasn’t any statistically significant difference regarding the incidence of at

least one AE neither during nor after treatment between both treatment groups

(probability index: 0.8875; 95% CI: 0.510; 1.544) (Table 5). No deaths were

reported, and none of the female participants got pregnant during the course of

the study.

One serious AE was reported

during treatment in the BFF 400/12 μg capsule group (cholelithiasis),

and one serious AE was reported during treatment in the BFF 320/9 μg group

(rash), which led to the definitive discontinuation of the study drug. The

investigator didn’t think those serious AEs were associated with the study

drug. No post-treatment SAEs were reported. None of the subjects interÂrupted

the treatment or discontinued the study due to pre- or post-treatment AE in the

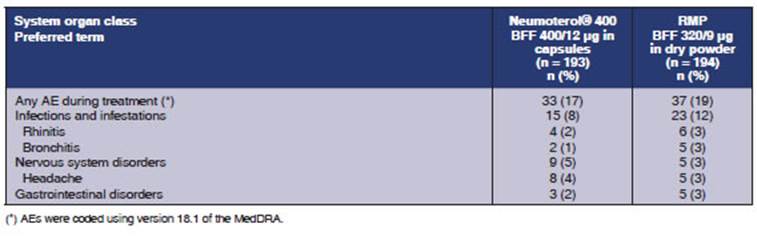

BFF 400/12 μg capsule group. The most frequently reported AEs

during treatment are summarized in Table 6. AEs reported in at least 2% of the

participants of any of the groups were: headache (4% and 3%, respectively),

rhinitis (2% and 3%) and bronchitis (1% and 3%).

The most frequently

reported post-treatment AEs were infections and infestations (4% for NeuÂmoterol® 400 [BFF 400/12 μg] and 5%

for the RMP [BFF 320/9 μg]), nervous system disorders (1% and 4%,

respectively), gastrointestinal disorders (2% and 2%), and musculoskeletal and

connective tissue disorders (2% and 0%). Headache was the only post-treatment

AE; it was reported by at least 2% of subjects (2% for BFF 400/12 μg and 0%

for BFF 320/9 μg).

The investigator

considered that two AEs durÂing treatment (palpitations and headache) and 1 AE

after treatment were associated with the BFF 400/12 μg

capsule. None of the AEs during or post-treatment were

considered to be associated with BFF 320/9 μg.

Two subjects (1%)

showed moderate asthma exacerbation during treatment with BFF 400/12 μg. One

participant (1%) showed moderate asthma exacerbation during treatment with BFF

320/9 μg. All these asthma exacerbations were resolved after

medical intervention. One patient showed moderate asthma exacerbation after

treatment, at the end of the BFF 320/9 μg treatment period, which was resolved.

No clinically

relevant differences were reÂported between the two treatments in the central

tendency for clinical biochemistry values at the baseline period or on day 29,

and no changes were reported, either, from the baseline period until day 29,

including glucose and potassium levels. No differences were observed between

the treatÂments in terms of changes in the arterial pressure or duration of the

QT interval from pre-dose until 30 min post-dose on day 29.

There was a small

increase in the heart rate, from pre-dose until 10 min post-dose on day 29 for

BFF 400/12 μg (mean increase in the LS of 1.3 beats/min), whereas

the heart rate for BFF 320/9 μg remained essentially invariable. This differÂence

between treatments regarding the change in the heart rate was statistically

significant (difference: 1.2 beats/min; 95% CI: 0.1; 2.3). The difference was

temporary, and there weren’t any differences between the BFF 400/12 μg capsule

and BFF 320/9 with respect to the change in the heart rate from pre-dose until

30 min post-dose on day 29 (difference: 0.2 beats/min; 95% CI –0.7; 1.2). No

tachycardia events were reported during the study, but one participant had an

AE of mild palpitations 3 d after the beginning of treatment with the BFF

400/12 μg capsule. No differences were observed between the

two treatments in terms of changes in systolic or diastolic arterial pressure

from pre-dose until 30 min after dose on day 29.

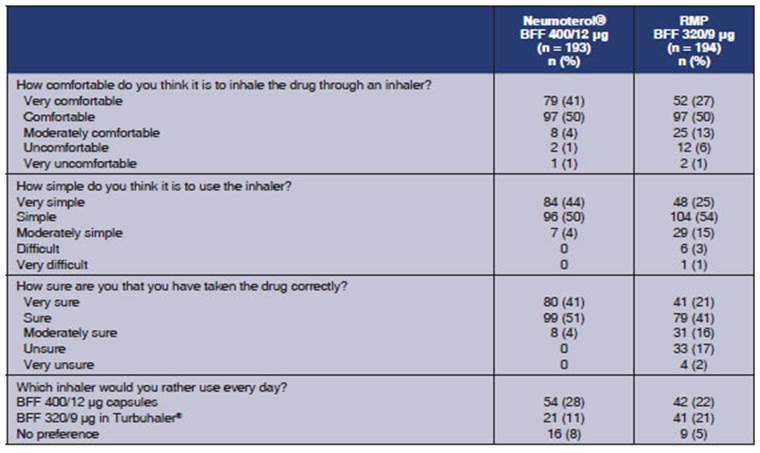

Exploratory endpoint:

The subjects’ preferÂence on the use of

the devices at the end of each treatment period was defined as an exploratory endpoint.

A higher proportion of subjects said that Neumoterol®

400 (BFF 400/12 μg) was “very comÂfortable to use” compared to the RMP

(BFF 320/9 μg), (41% versus 27%, respectively), and “very easy to

use” (44% versus 25%), and felt very confident that they had used the

medication satisfactorily (41% versus 21%). In general, more participants

expressed their preference for the Neumoterol® 400 (BFF 400/12 μg)

inhaler, 50% versus 32%. Table 7 provides a detailed description.

DISCUSSION

Asthma is a serious

worldwide health problem. There is increasing asthma prevalence in many countries,

especially in pediatric populations. This disease imposes an unacceptable

burden on healthcare systems and loss of work productivity.2

This phase IV study

demonstrated the non-inÂferiority of the efficacy of a BFF 400/12 μg capsule

inhaler (Neumoterol® 400) in comparison with the

RMP (BFF 320/9 μg) administered twice daily in asthmatic adults. BFF

400/12 μg (Neumoterol®

400) showed improvements in the parameters of the pulmonary

function and symptom control at the end of the 4-week treatment period.

It is important to

mention that no differÂence was reported between the two treatments in terms of

incidence of AEs or SAEs, neither during treatment nor after the treatment. In

general, the safety profile of both treatment strategies was similar to the one

reported before for BFF.10 Two

serious AEs were reported, but none of them was considered to be associated

with the study drug.

No difference was

reported between the two treatment strategies regarding the change from the

baseline period until day 29 in pre-dose heart rate, pre-dose arterial

pressure, predose QTc, or

the glucose or potassium levels.

It is interesting to

highlight the fact that an exploratory evaluation of the patients’ preference

on the use of the devices showed that a higher proportion of subjects expressed

global preference for the BFF 400/12 μg capsule in comparison with the inhalation of the RMP

with BFF 320/9 μg (50% versus 32%, respectively). Few studies

evaluated the preference of patients diagnosed with asthma or COPD11

with regard to inhalation devices. This aspect represents a key

factor in the improvement of treatment compliance.

This study has some

limitations: The fact that this is an open-label study could be considered a

weakness, but, to conduct a blind study with drugs administered through

inhalation where the device is not interchangeable is not possible. For that

reason, in order to improve the sensitivity of the study, a crossover design

was used instead of a parallel study. Furthermore, the open-label modality also

allowed the exploratory assessment of the patient’s preference on the type of

device.

Other limitations:

randomization per center and the performance of non-centralized spirometries with comparable yet different equipment,

accordÂing to each center.

CONCLUSIONS

The non-inferiority

of Neumoterol® 400 (BFF 400/12 μg)

evaluated in asthmatic adults was demÂonstrated, compared to the RMP (BFF 320/9

μg). A favorable tendency was observed with BFF 400/12

in the improvement of the pulmonary function on day 1 (AUC 0-10 FEV1) and in symptom control (ACT)

on day 29.

Both formulations

were well-tolerated, and their safety profile was congruent with previous

investigations. No serious AEs were reported in asÂsociation with the study

drug. A minimum (though statistically significant) change was described in the

heart rate from pre-dose until 10 min post-dose on day 29, which was bigger for

the BFF 400/12 μg capsule compared to the RMP BFF 320/9 μg; however,

this difference in the heart rate change was transitory and was no longer

observed after 30 min (difference: 0.2 beats/min; 95% CI –0.7; 1.2). A higher

proportion of patients expressed global preference for the Neumoterol®

400 capsule (BFF 400/12 μg). We believe that the study results generÂate new

clinical evidence of the safety and efficacy of this formulation, so heavily

used in Argentina.

REFERENCES

1. Mallol J, Solé D, Asher I,

et al. Prevalence of asthma symptoms in Latin America: The International Study

of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood (ISAAC). Pediatr

Pulmonol. 2000;30:439-44.

https://doi.org/10.1002/1099- 0496(200012)30:6<439::AID-PPUL1>3.0.CO;2-E

2. Global Initiative

for Asthma (GINA). Gina Report, Global Strategy for Asthma Management and

Prevention, 2016. In: www.ginasthma.org

3. Symbicort Turbohaler 400/12,

Inhalation powder.In:

https://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/medicine/11882 AcÂcessed: September 20th,

2017.

4. Argentina Census

2010 Data. In: http://www.indec.gov.ar/nivel2_default.asp?id_tema=2&seccion=P

Accessed: September 19th, 2017.

5. Quanjer PH, Stanojevic S, Cole

TJ, et al. Multi-ethnic referÂence values for spirometry

for the 3-95-yr age range: the globÂal lung function 2012 equations. Eur Respir J. 2012;40:1324- 43. https://doi.org/10.1183/09031936.00080312

6. Nathan RA, Sorkness CA, Kosinski M, et al.

DevelopÂment of the asthma control test: a survey for assessing asthma control.

J Allergy Clin Immunol.

2004;113:59-65.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaci.2003.09.008

7. Miller MR,

Hankinson J, Brusasco V, et al; ATS/ERS Task Force. Standardisation

of spirometry. Eur Respir J. 2005;26:319-38.

https://doi.org/10.1183/09031936.05.00034805291

Non-Inferiority Study

of the Efficacy of Two Budenoside/Formoterol

Formulations

8. GlaxoSmithKline. GSK Clinical

Study Register. In: http:// www.gsk-clinicalstudyregister.com/study/112202#ps

AcÂcessed: Sep 21st, 2017.

9. Santanello

NC, Zhang J, Seidenberg B, et al. What are minimal important changes for asthma

measures in a clinical trial? Eur Respir

J. 1999;14:23-7 https://doi.org/10.1034/j.1399-3003.1999.14a06.x

10. Buhl R. Budesonide/formoterol for the treatment of asthma. Expert

Opin Pharmacother.

2003;4:1393-406. https://doi.org/10.1517/14656566.4.8.1393

11. Bereza

BG, Troelsgaard Nielsen A, Valgardsson

S, et al. Patient preferences in severe COPD and asthma: a comÂprehensive

literature review. Int J Chron

Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2015;10:739-44.

https://doi.org/10.2147/COPD.S82179