Autor : Pascansky, Daniel1-2, SĂvori, MartĂn1-2, Capelli, Luciano1-2

1Pneumophthisiology Unit, Hospital de Agudos Dr. J. M. Ramos MejĂa, Autonomous City of Buenos Aires. 2Centro Universitario NeumonologĂa Dr. J. M. Ramos MejĂa. Faculty of Medicine, University of Buenos Aires. Argentina.

https://doi.org./10.56538/ramr.LYBB1788

Correspondencia : Daniel Pascansky, PneumoÂphthisiology Unit, Hospital General de Agudos Dr. J. M. Ramos MejĂa, Urquiza 609, 1221 Buenos Aires, Argentina e-mail: vdpascan@gmail.com

ABSTRACT

There is not information about

the annual and structure of costs of a hospitalization of COPD exacerbation in

our country actually.

Objective: To determine the structure of direct costs in hospitalized patients due

to COPD exacerbations in a public hospital of Buenos Aires in 2018.

Methods: Patients hospitalized of COPD exacerbation (GOLD) in 2018 were analyzed

in our hospital. Direct costs were determined (financier perspective), due to

modulation of the Health Ministry of Buenos Aires City Government, stratified

by Intensive Care Unit hospitalization and in room at June 2021, in dollars

(dol.), parity at June 30th 2021 was 1 dollar = 101,17$ (price Banco

Nación).

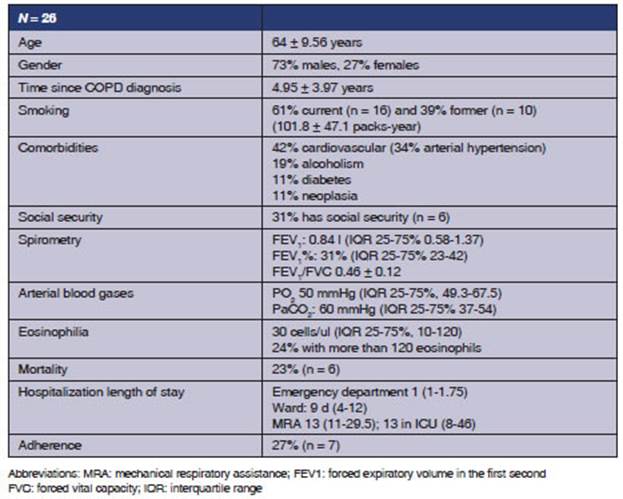

Results: 26 patients were hospitalized: age 64 ± 9.56 years, male gender 73%, 61%

actual smokers and 39% ex-smokers (101.8 ± 47.1 pack-y, social health assurance

31% (n = 8); FEV1%

31 median (23-42) and FEV1/FVC

0,46 ± 0,12. Ward length of hospitalization (median) was 1 day (1-1,75), 9 days

in room (4-12), 13 days in UCI (11- 29,5) with mortality rate 23% (n = 6).

Final direct cost by patient was

1462,62 dol, median (IQR

25%-75%,763,85-2915,95),at 162,44 dol./day/patient. Total cost (n = 26)

was 117 480 dol. UCI cost was median 9898,28

dol./patient (IQR 25%-75%, 6700,94-35 780,25). Final UCI total cost (n = 3) 75 942,3 dol.

Conclusion: Patients with COPD exacerbation hospitalized were mainly males, sixty

years old, heavy smokers and severe airway obstruction. With financier

perspective, direct cost of hospitalization was 1462 dol./patient,

almost seven times higher in UCI. Disease management program must be

implemented to manage COPD, to identify patients at risk, to educate and to

assure access to drugs.

Key words: COPD, Exacerbations, Hospitalizations, Costs, Expense

RESUMEN

No existe información sobre la estructura y costos

anuales de una hospitalización por agudización de la EPOC en

nuestro país actualmente

Objetivos: Determinar la estructura de costos de los pacientes hospitalizados por EPOC

reagudizada en un hospital público de la Ciudad Autónoma de

Buenos Aires (CABA) en el año 2018.

Materiales y métodos: Se evaluaron pacientes con EPOC reagudizada (GOLD), inÂternados durante 2018

en nuestro hospital. Se determinaron costos directos (perspecÂtiva del

financiador), según costos de medicamentos y la modulación de

internación clínica y Unidad de Terapia Intensiva (UTI) del

Gobierno de CABA a junio de 2021, valor dólar Banco Nación al 30

de Junio 2021 de $101,17.

Resultados: Se internaron 26 pacientes, edad 64 ± 9,56 años, masculino 73%, 61%

tabaquistas actuales y 39% extabaquistas (101,8 ±

47,1 paq.-año), seguro social 31%, FEV1% 31 mediana

(23-42) y FEV1/FVC 0,46

± 0,12. La duración de internación fue: guardia 1 d (1-1,75);

piso, 9 d (4-12); y UTI, 13 d (11-29,5), con mortalidad 23% (n = 6).

El costo final fue 1462,62 dólares/paciente,

mediana (RIQ 25%-75%,763,85-2915,95), 162,44 dólares/d/paciente, y el

costo total (n = 26) fue USD 117 480. El costo de UTI fue 9898,28

dólares/paciente, mediana (RIQ 25%-75%, 6700,94-35 780,25). El costo

total (n = 3) fue USD 75 064,11.

Conclusión: Los pacientes con EPOC reagudizada que se hospitalizan son en su

mayoría hombres, más de 60 años, alta carga

tabáquica y obstrucción grave. El costo directo desde la

perspectiva del financiador fue de USD 1462 por paciente; el costo del paciente

que se hospitaliza en UTI fue casi siete veces superior. Se deben instruÂmentar

programas sistematizados de manejo de la EPOC para identificar pacientes con

factores de riesgo, educar y permitir acceso a la medicación.

Palabras claves: EPOC, Exacerbaciones, Hospitalizaciones, Costo directo, Gastos

Received: 5/2/2022

Aceptado: 11/3/2022

Chronic obstructive pulmonary

disease (COPD) is an important public health problem because there is growing

evidence of the increase in diffeÂrent epidemiological parameters of

considerable concern.1 Smoking is

the main cause of COPD.2,

3 The

smoking prevalence has been decreasing from rates of around 40%, at the

beginning of this century, up to near 22% of the general population, according

to the national Health Survey of our couÂntry.4

The age of smoking initiation in our country is 14 years; the age

of regular consumption is 18, and a tendency to increase consumption is obserÂved,

particularly in the areas of young people of low income.2, 4 Clearly, smoking cessation is still the main

therapeutic intervention that improves morÂbidity and mortality.2, 3 It is

important to highlight the underdiagnosis reflected in several European

studies, of around 75% of the total number of patients with COPD.5-7 In the

PLATINO study of five cities of Latin America, 82% of COPD patients were

unaware that they had this disease, with 77.4% in the Argentinian prevalence

study, EPOC.AR.8,

9 COPD

prevalence in the urban general poÂpulation of Argentina is 14.3%, but in a

sample of a population of more than 40 years with exposure to tobacco (PUMA

study) it is higher (29.6%), thus estimating between 2.5 and 3 million patients

with COPD.10 With

regard to mortality, according to the WHO, it is still the third cause of

death, and 80% occurs in countries of low- or middle- income.11

Preliminary studies about COPD mortality in our country show 112%

growth compared to 1980, and reaching almost 27 deaths per 100,000 inhabitants

in 1998, approximately 5000 deceased, especiaÂlly women.12

Recently, the National Institute of Respiratory Diseases “Dr.

Emilio Coni” reported approximately 30,000 annual hospitalizations in part of

the public sector in 2015.13

With respect to the morbidity,

COPD is the fifth cause of hospitalization in Argentina in individuals older

than 60 years.3 In the United

States of North America, hospitalizations have increased between 1978 and 1994

from 259,000 to 500,000 per year, especially in individuals older than 65

years.15 As a

disabling disease, COPD will go up from the current 12th place to the 5th place

throughout the world.16 The

increasing cost of chronic diseases has required the analysis of the impact of

the diseases on the health system, the cost structure, and the approaches that

tend to optimize the system, since the demand is always growing and not satisfied,

and health-related costs increase year after year. The progressive increase in

life expectancy, the use of diagnostic techniques that are becoming more and

more costly, and more expensive treatments had to be weighted in relation to

the savings generated by the reduction in the use of health resources, the

increase in survival and the improvement in different health markers, such as

quality of life.16-22 The National

Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) of the United States acknowledged USD

23.9 billion in COPD expenses, 61.5% for direct costs. The cost per person was

USD 1,522 per person, per year, three times higher than the cost of asthma and

2.5 times higher than not-COPD.15,

21 The

highest costs were the direct costs for hospitalization and visits to the

emergency department (72.8%).22

In a study on emphysema costs in Great Britain, from the National

Institute for Health of the United Kingdom, Guest et al determined an

expenditure of ÂŁ19 million (approximately USD 34 million) to treat 134,000 emphysema

exacerbations (direct costs): 50% for hospitalization costs to treat 3% of

total exacerbations.23 The average

hospitalization cost was USD 3,600 versus USD 128 for exacerÂbations treated on

an outpatient basis. For that reason, strategies have been created to reduce

the number of hospitalizations and their length.23, 24 The average hospital

stay was 9.9 d. The mean estimation per hospitalization was ÂŁ 3,000 (USD 5,700)

as opposed to ÂŁ 100 (USD 190) for outpatient treatment.24

There are other multiple U.S and European publications about the

cost structure of COPD, all of them with the common denominator of the high

percentage of hospitalization due to exacerbation and oxygen therapy, which

severely impacts on the total cost of this disease.25-44

In Argentina, there is only one

publication from twenty years ago about the impact on directs costs of

hospitalizations for exacerbated COPD: 33 patients in 1999, in a public

hospital of the GoverÂnment of the City of Buenos Aires.36

The cost per discharge was USD 2,451, with an average stay of 15

d, at USD 163 per hospitalization day.36

The purpose of this study was to

describe the direct cost per each hospitalization for COPD exaÂcerbation and to

determine the cost structure in a public hospital of the city of Buenos Aires

in 2018.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

We reviewed the medical records

of patients hospiÂtalized for exacerbated COPD in every area of the Hospital

General de Agudos Dr. J. M. Ramos Mejía of the Autonomous City of Buenos

Aires (CABA) from January 1st, 2018 until December 31sr, 2018. Adults older

than 18 years were included. Patients with COPD (GOLD definition: FEV1/FVC

ratio < 0.70 and postbronchodilator predicted FEV1 < 80%2), older than 40 years, with smoking history

(more than 20 packs of cigarettes per year). PaÂtients with history of other

respiratory diseases were excluded.

Direct costs were determined from

the funder’s perspective, taking into account the cost of mediÂcations and the

modulation of the Government of the City of Buenos Aires (GCBA, for its acronym

in Spanish) for hospitalization in the intensive care unit (ICU) and regular

ward in June 2021. The values of the government’s modulation for public

hospitals by June 2021 were: ARS 14,143 (USD 139) for hospitalization in the

ward, per patient, per day; non-critical emergency room, ARS 2,957 (USD 30);

emergency room including tests, ARS 5,231 (USD 51.5); critical emergency room,

ARS 33,070 (USD 325); at the ICU, without mechanical respiratory assistance

(MRA), ARS 29,527 (USD 290); and with MRA, ARS 33,070 (USD 325) per patient,

per day.45 Each

module had certain pre-established number and type of service (biochemistry,

imaging, electrocardiogram, spiroÂmetry, MRA, oxygen, disposable material,

drugs, etc., apart from the rate that depends on salaries, taxes and charges,

administrative fees, equipment amortization, food and laundry costs, etc.). WheÂnever

a patient had any additional consultation, diagnostic practice or treatment

(for example, drugs) outside modulated fees, the cost was calÂculated from the

funder’s perspective according to the KAIROS pharmaceutical vademecum and the

list of services of the GCBA nomenclature.46 Given the varying peso/dollar parity,

results shall be reported in dollars. The exchange rate used to calculate the

cost in dollars was based on the quote of the Banco Nación on June 30th,

2021 ($ 101.17 = USD 1).

The eosinophilia value was

obtained before the administration of systemic corticosteroids at the

laboratory of the emergency department.

The spirometry was performed the

last hospitaÂlization day, before discharging the patient.

Descriptive statistics were used.

For quantiÂtative variables with non-Gaussian distribution, we used the median

as central measure and the interquartile range 25%-75% (IQR 25%-75%) as

dispersion measure. In order to have a gaussian distribution, we used the mean

as central measure and standard deviation as dispersion measure, and for

qualitative variables, we used percentages.

RESULTS

During 2018, 26 patients were

hospitalized: 23 in the regular ward and 3 in the ICU. Table 1 shows the

demographic characteristics.

Most patients (n = 18 patients

[70%]) belonged to the programmatic area of the hospital. From all the

patients, only 38.6% (n = 10) had been treated in our hospital before

their consultation. Adherence to treatment before hospitalization was poor

(27%).

Upon admission, 50% (n =

13) of the patients were receiving treatment with short-action beta- 2

adrenergic bronchodilators; 23% (n = 6), with combination of

short-action beta-2 adrenergic and anticholinergic bronchodilators; 15% (n =

4), with a combination of long-action beta-2 adrenergic bronÂchodilators and

inhaled corticosteroids; and 11% (n = 3), with long-action

anticholinergic bronchodilators. None of the patients were treated with triple

therapy.

Three of the 26 patients (11.5%)

were hospitaÂlized twice.

Direct cost analysis

The final direct cost per

hospitalized patient in the regular ward was USD 1,462.62 (IQR 25%- 75%,

763.85-2,915.95), which considering the 26 hospitalized patients, gives a total

direct cost of USD 117,480, that is, USD 162.44 per patient, per day.

The final direct cost per

hospitalized patient at the ICU was USD 9,898.28 (IQR 25%-75%,

6,700.94-35,780.25). Taking into account the fact that only three patients were

hospitalized at the ICU, there was an important dispersion of the total direct

cost per patient. The total amount spent for three patients was USD 75,064.11.

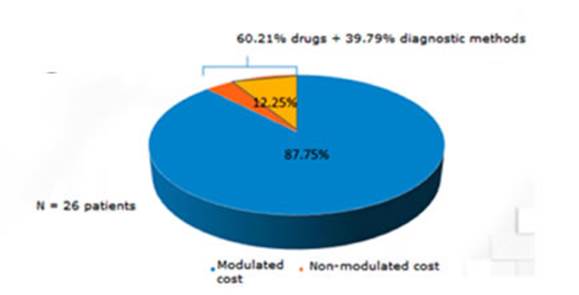

With regard to the direct cost

structure, 87.75% of it had been considered inside the clinical module of the

GCBA. However, 60.21% of the rest (12.25%) was related to drugs not included in

the module, and 39.8% to diagnostic practices not included in the module

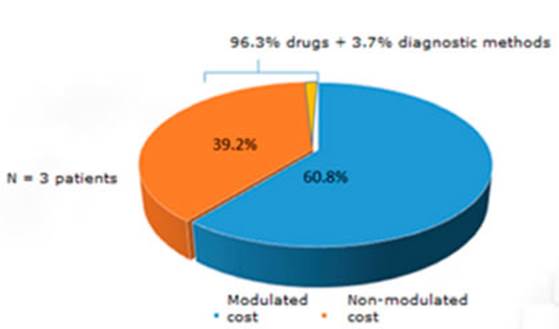

(Figure 1). But, if we consider ICU hospitalization, 39.2% of the direct cost

wasn’t modulated (three times higher than patients hosÂpitalized

in the regular ward). The cost of drugs (specially

antibiotics) was the main cause of non-modulated direct cost (96.3%) (Figure 2).

DISCUSSION

The direct cost of exacerbated

COPD hospitalizaÂtion in a public hospital in the Autonomous City of Buenos

Aires has been established. The sample consisted of 26 patients, mostly males

aged in their 70s, with recently diagnosed disease, high smoking load and

severe obstruction of the airflow. The cost in the regular ward was USD 1,462

per patient, and almost seven times higher in the ICU. Patients hospitalized in

the regular ward were included in the expected cost module, whereas those from

the ICU had a higher percentage outside the module, due to the use of high-cost

drugs. The pharmaÂcological treatment profile of most patients in public

hospitals in CABA is not included in the recommendations of current guidelines,

since it is mainly based on the use short-acting bronchoÂdilators, surely due

to the difficulty with access to medication and poor adherence to follow-up.

For the European

Union, total annual direct costs of respiratory diseases account for 6% of the

total healthcare budget; COPD represents 56% (38.6 billion Euros).2, 47

In United States, total annual direct costs for COPD are calculated in USD 29.5

billion, and indirect costs, USD 20.4 billion.2, 48 The highest proportion is

related to COPD exacerbation care, which determines a diÂrect relationship with

the severity of the disease. Probably in underdeveloped countries the indirect

cost is higher than the negative impact on the direct cost.2, 36-43

Given the fact that

mortality only offers a limited perspective of the impact of a disease on the

human being, Murray et al designed a DALY indicator (Disability-Adjusted Life

Year) that was analyzed in the Global Burden of Disease Study; it is the

sum of years of life lost due to premature death adjusted by the severity of

the disease and concomitant impairment of quality of life.49 So, in

2005 COPD was the eighth cause of DALY lost in the world, and it was estimated

that in 2013 it was the fifth cause worldwide, though second in the United

States, after coronary disease.49

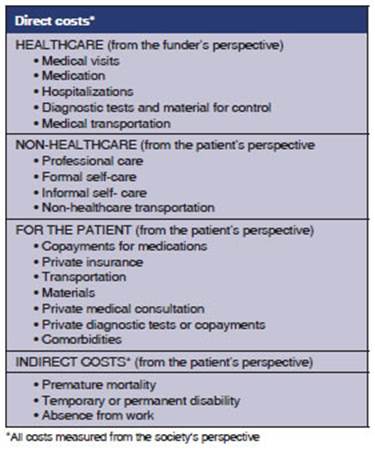

The Asthma Management

Spanish Guidelines (GEMA, for its acronym in Spanish) have deterÂmined the

different elements of the direct and indirect cost of asthma, which can be

extrapolated to another chronic obstructive disease, such as COPD. The

Guidelines recommend forty seven features to be used in a cost study (Table 2).50

Our study implements those recommendations. A mixed

methodology has been used to determiÂne direct costs: modulation of costs

provided by the GCBA (top-down method) and, apart from reviewing all medical

records, covering patient’s consumption outside the modulation (bottom-up

method). In our study, direct primary data have been collected from the medical

records, and that is very valuable information.50 As

we have already mentioned, we conducted the cost study from the funder’s

perspective (GCBA) in the environment of a public general acute care hospital,

thus, the conclusion will only be extrapolated to that health system. Cost

comparison between countries or diÂrect extrapolation are not recommended,

because cost structure and health systems vary from one country to another,

although it may help by giving us an idea of the magnitude of the problem and

the qualitative strength of each variable.50

Bilde et al published

a study on Medicare spenÂding per person, comparing COPD patients with non-COPD

patients. They determined that the cost was USD 8,482 versus USD 3,511 (2.5

times higher). 50% of the cost of COPD is consumed in 10% of the patients.51

Other authors have reported the economic impact of

COPD on the North AmeriÂcan Health System. The average days/bed was 7.75 d, but

with higher rates of rehospitalization and higher expenses. The average cost

was USD 6,469 per patient (direct costs), 68% of which belonged to

hospitalizations.48, 52 It has already been said that the National

Heart, Lung, and Blood InstiÂtute (NHLBI) of the United States acknowledged a

COPD cost of USD 23.9 billion: 14.7 billion were direct costs (61.5%) and 9.2

were indirect costs (38.5%). The cost per person was USD 1,522 per year, three

times higher than the cost of asthma and 2.5 higher than non-COPD patients.15,

21 The hospitalization index was 21.2 patients

for every 1000 persons. The highest direct costs were from hospitalization and

visits to the emergency department (72.8%). The rest was divided: 15% for

outpatient visits and 12.2% for cost of drugs. But the distribution of COPD

expenses was very disproportionate: 10% of patients used 73% of the total

expenses.15, 21 The increase in the number

of hospitalizations was observed in patients older than 45 years. The NHLBI

report includes a comÂparison within respiratory diseases, between the

distribution of direct and indirect costs of COPD with asthma, influenza, pneumonia,

tuberculosis and lung cancer.15 COPD uses twice the amount of

asthma, and compared to influenza, lung cancer or pneumonia, it shows a higher

proportion of direct costs.15 Guest et al, in the first study

on emphyÂsema costs in Great Britain, from the National Institute of Health of

the United Kingdom, deterÂmined a cost of ÂŁ 19 million (approximately USD 34

million) to treat 134,000 exacerbations due to emphysema (direct costs): 50%

for hospital costs to treat 3% of total exacerbations.23 The average cost per

hospitalization was USD 3,600 versus USD 128 in exacerbations treated on an

outpatient basis. This allowed the creation of strategies to reduce the number

of hospitalizations and their length.17 Again, Guest et al conducted

another study, similar to the previous one, but taking into account the general

COPD costs in the National System of Health of the United Kingdom. An amount of

ÂŁ 817.5 million (USD 1.553 billion, approximately) was determined, only

including direct costs.24 This is equivalent to ÂŁ 1,154

per person per year, around USD 2,300 per person per year.24 The average stay was 9.9 days.

Hospital expenses were 35% of the total to treat less than 2% of exacerbations.24

The mean calculation per hospitalization was ÂŁ 3,000 (USD 5,700),

as opposed to ÂŁ 100 (USD 190) for outpatient treatment.24 Probably this analysis

underestimates the real cost for the society, since it doesn’t consider

indirect costs (loss of producÂtivity, because COPD has 6 times more absence

from work than asthma), direct costs for the paÂtient (trips), or intangible

costs (quality of life). If we analyze the distribution of direct costs in the

United Kingdom, 47.5% was used for the purchase of drugs; 24.5% for home oxygen

therapy; 17.8% for hospital fees and 10.2% for medical outpatient fees.23, 24

With regard to COPD

hospitalization in ArgenÂtina, the National Institute of Respiratory DiseaÂses

“Dr. Emilio Coni” has informed that in 2015 almost 30,500 hospitalizations were

reported for exacerbated COPD in a sample including public institutions of the

country.13

In the GCBA, in 2013, there were 1,066 hospitalizations, and in

2014, 996 hospitalizations for exacerbated COPD.53

According to the

previous cost analysis in paÂtients with exacerbated COPD, twenty years ago,

including 33 patients, the total direct cost per hospitalized patient was USD

2,451. The structure of hospital costs was distributed as follows: costs of

final services represented 75% of total costs; 57% of those belonged to

salaries (17.55% for physicians, 37.41% for nurses and 1.51% for administrative

employees), and 13% to drugs, disposable maÂterials and medical practice

(drugs; 8.8% of the total amount).36 The remaining 25% was related

to the transfer of costs from general services and other services, with 12.48%

for the staff.36 The hospitalization day was

USD 163, the same as the cost per hospitalization day of the current analyÂsis

(USD 162), that is to say, it remained stable throughout two decades. It is

worth mentioning that oxygen therapy provided at the emergency department, the

regular ward and ICU represents a high hospital cost in all the cost analyses

of the disease. In our case, it is considered as part of the hospitalization

module, just like the use of invasive and non-invasive ventilation is

considered within the ICU module. At the time this study was being conducted,

the high-flow oxygen cannula wasn’t available.

Regarding the mean

hospitalization days of our current study, it has been reduced to 9 days, which

is a lot less than the average of this same institution twenty years ago (15

days). The average number of hospitalization days is similar to the one

reported internationally: 9.9 d in Great Britain and 7.75 d in the United

States.22-24, 36 One possible explanation could

be that the standardization of treatment and permanent training of healthcare

staff in our institution for the adequate and updaÂted management of patients

with COPD, as well as the availability of more effective pharmacological

treatments, have allowed a significant reduction in hospital length of stay.

Different international Guidelines (GOLD, ALAT, GESEPOC and others), plus the

Guidelines from the Ministry of Health of our country summarize the

recommendations for the effective management of COPD, with bronchoÂdilator

therapy as the cornerstone.2, 3, 54, 55

Both the

international and the national GuiÂdelines identify a group of patients who

share the fact of having been hospitalized the year before or more than one

outpatient exacerbation requiring antibiotics or systemic corticosteroids

(GROUPS C and D of the GOLD Guidelines). Given the worst prognosis of patients

who have suffered frequent exacerbations, with higher impairment of the

pulmonary function, symptoms, quality of life and mortality, the frequent

exacerbator phenotype is considered by all the Guidelines as the risk factor

with the worst prognosis, and deserves a more intensive treatment, even with

the use of inhaled corticosteroids.2, 3, 54-57 Other factors known as

hospitalization risks in COPD are: difficulty in accessing the pharmacological

treatment, nonadÂherence, inhalation errors and comorbidities.2,

3, 54, 55 In

our study, only 10% of patients had social seÂcurity. Also, the high prevalence

of mistakes in the administration of inhaled drugs in patients with chronic

obstructive diseases, such as asthma and COPD, is well-known around the world.58

Usmani et al determined that advanced age, low socioecoÂnomic

status and low educational level, the lack of previous training in the correct

inhalation therapy, and the presence of comorbidities were the factors

associated with the mistakes in the administraÂtion technique; all of this

related to bad asthma control and an increase in the use of healthcare

resources.59 With respect to comorbidities,

there was high prevalence in our study (Table 1), and it is known that they

have a bearing on the worst disease prognosis, both in the exacerbator

phenotype (groups C and D) and in the non-exacerbator group (Group B).2, 3, 54, 55, 60, 61

Regarding the

limitations of this study, we can say that data collection from the medical

records was retrospective. Another limitation is the fact that the

extrapolation of conclusions for other health systems in our country or other

regions (external validity) is not recommended, due to the different cost

structures, as we have already mentioned. Indirect costs haven’t been evaluated

(they are thought to be higher than direct costs, basing on previously reviewed

information), and costs haven’t been determined from other persÂpectives

(patient or society). Costs were initially calculated in pesos, but due to the

exchange rate instability and the devaluation suffered by our country in the

last years we decided to express the results in dollars. Finally, the

modulation used by the GCBA didn’t allow us to separate the internal cost

structure to know which variables have been considered, and to what extent.

To conclude, after

twenty years, a direct cost study of COPD exacerbation in hospitalized paÂtients

in a public hospital of CABA has been carried out again. The sample consists

mostly of men older than 60 years, with poor follow-up, high smoking load and

severe obstruction of the airflow. The direct cost from the funder’s

perspective was USD 1,462 per patient; the cost of a patient hospitalized at

the ICU was almost seven times higher. But we have to take into account that

only three patients were admitted to the ICU, and there was great disÂpersion

in the cost per patient. Most of the costs for ward hospitalizations had been

calculated in the module, but not in the case of the ICU, which uses high-cost

drugs. A significant reduction has been shown in hospitalization length of

stay, but with a day-bed cost that remained stable throughout 20 years (USD

162-163). Probably the indirect cost is much higher. We suggest the need to

include this type of study in the hospital environment for the purpose of

collecting data to allow a better management of the available resources.

Including cost-related problems in every affected area could contribute to the

management of available resouÂrces, the planning, organization and systematizaÂtion

of patient care, thus improving the production and quality of the end-product

with equal or lower budget. Being the management of COPD patients the most

important element of direct costs, systeÂmatic COPD management programs shall

be imÂplemented for the purpose of identifying patients with risk factors,

educating them about treatment adherence and allowing access to medication, in

order to reduce the number of hospitalizations for exacerbations and, why not,

the mortality.

Conflict of interest

Dr. Daniel Pascansky

has participated in continuous meÂdical education programs for GSK,

AstraZeneca, ELEA, Casasco and Novartis.

Dr. Martín

Sívori has participated in continuous meÂdical education programs for

GSK, AstraZeneca, TEVA and ELEA.

Dr. Luciano Capelli

has no conflict of interest to declare.

REFERENCES

1. Ball P, Make B. Acute

exacerbation of chronic bronchitis: An international comparison. Chest 1998;113:199S-204S.

https://doi.org/10.1378/chest.113.3_Supplement.199S

2. Global Strategy

for the Diagnosis, Management, and Prevention of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary

Disease. NHLBI/WHO. Workshop

Report. 2023. Acceso en www.goldcopd.com. Consultado

el 14 Noviembre de 2022.

3. Figueroa Casas JC, Schiavi

E, Mazzei JA, et al. RecomendacioÂnes para la

prevención, diagnóstico y tratamiento de la EPOC en Argentina.

Medicina (B Aires) 2012;72 (Supl.I):1-33.

4. Cuarta Encuesta Nacional de Salud.

Ministerio de Salud. Argentina. 2018. Acceso en https://www.indec.gob.ar/ftp/cuadros/publicaciones/enfr_2018_resultados_definitivos.pdf. Consultado el 10 de

Marzo 2022

5. Sullivan S, Ramsey S, Lee T. The economic burden of COPD. Chest 2000;117:5S-9S.

https://doi.org/10.1378/chest.117.2_suppl.5S

6. Miravitlles M, Soriano JB, Garcia Rio F, et al. Prevalence of COPD in Spain: impact of undiagnosed COD on quialÂity of life and daily life activities (EPISCAN). Thorax 2009;64:863-8.

https://doi.org/10.1136/thx.2009.115725

7. Sobradillo Peña V, Miravitlles

M, Gabriel R, et al. GeoÂgraphic

Variations in Prevalence and Underdiagnosis of COPD:

Results of the IBERPOC Multicentre EpidemiologiÂcal

Study. Chest 2000;118:981-9. https://doi.org/10.1378/

chest.118.4.981

8. Menezes

AMB, Perez-Padilla R, Jardim JB, et al. Chronic obÂstructive

pulmonary disease in five Latin American cities (the PLATINO study): a

prevalence study. Lancet 2005;366:1875- 81.

https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67632-5

9. Echazarreta AL, Arias SJ,

del Olmo R, et al. Prevalencia de EPOC en 6 aglomerados urbanos de Argentina:

el estudio EPOC.AR. Arch Bronconeumol

2018;54:260-9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arbres.2017.09.018

10. Schiavi E, Stirbulov R, Hernández Vecino R, Mercurio S, Di Boscio V, PUMA Team. COPD Screening in Primary Care in Four Latin American Countries:

Methodology of the PUMA Study. Arch Bronconeumol 2014;50:469-74. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arbr.2014.09.010

11. World Health Organization. World Health Statistics 2022. Acceso

1 Octubre de 2022 en https://www.who.int/data/gho/

publications/world-health-statistics

12. Sivori M, Saenz C, Riva Posse C. Mortalidad

por Asma y EPOC en la Argentina de 1980 a 1998. Medicina (B Aires) 2001;61:513-21.

13. Bossio JC, Arias S.

Actualización de datos epidemiológicos sobre la EPOC. Instituto

Nacional de Epidemiología “Dr. Emilio Coni”.2020. (información

personal).

14. Mannino

DM, Buist AS. Global burden of COPD: risk facÂtors,

prevalence, and future trends. Lancet 2007;370:765-

73. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61380-4

15. Foster TS, Miller JD, Marton JP, Caloyeras JP, Russell

MW, Menzin J. Assessment of the economic burden of

COPD in the US: a reviews and synthesis of the literature. J COPD 2006;3:211-8. https://doi.org/10.1080/15412550601009396

16. Newhouse JP. Medical care

costs: how much welfare loss? J Econ

Persp 1992; 6: 3-21.

https://doi.org/10.1257/jep.6.3.3

17. Sculpher MJ, Pang FS, Manca A, et al. General disability in economic evaluation studies in healthcare: a

review and case studies. Health Technol Assess 2004;8:1-19. https://doi.org/10.3310/hta8490

18. Hilleman

DE, Dewan N, Malesker M,

Friedman M. PharmaÂcoeconomic evaluation of COPD.

Chest 2000;118:1278-85.

https://doi.org/10.1378/chest.118.5.1278

19. Starkie

JH, Briggs AH, Chambers MG. Pharmacoeconomics in COPD: lessons for the future.

Int J COPD 2008;3:71-8.

20. Del Negro R. Optimizing

economic outcomes in the manÂagement of COPD. Int J COPD 2008;3:1-10.

https://doi. org/10.2147/COPD.S671

21. Chapman KR. Epidemiology and

costs of chronic obstrucÂtive pulmonary disease. Eur Respir J 2006; 27: 188-207.

https://doi.org/10.1183/09031936.06.00024505

22. Sharafkhaneh

A, Petersen NJ, Yu HJ, Dalal AA, Johmson

Ml, Hanania NA. Burden of COPD in a

government health care system. Int J COPD 2010;6:125-32.

23. Guest J. Assessing the cost

of illness of emphysema. Dis Manage Health Outcomes 1998;3:81-8.

https://doi. org/10.2165/00115677-199803020-00004

24. Guest J. The

annual cost of chronic obstructive pulmoÂnary disease to the UK´s National

Health Service. Dis Manage Health Outcomes 1999;5:93-100.

https://doi.org/10.2165/00115677-199905020-00004

25. Miravitlles

M, Murio C, Guerrero T, Gisbert

R. Costs of chronic bronchitis and COPD: a 1-year follow-up study. Chest 2003;123:784-91. https://doi.org/10.1378/ chest.123.3.784

26. Jansson

S, Andersson F, Borg S, et al. Costs of COPD in

Sweden according to disease severity. Chest 2002;122:1994-

2002. https://doi.org/10.1378/chest.122.6.1994

27. Pelletier-Fleury

N, Lanoe JL, Fleury B, Fardeau M. The cost of treating COPD

patients with long-term oxygen therapy in a French population. Chest

1996;110:411-6. https://doi.org/10.1378/chest.110.2.411

28. Nielsen R, Johannssen A, Bendiktsdottir B,

et al. The economic burden of COPD in a US Medicare

population. Respir Med 2008;102:1248-56.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rmed.2008.04.009

29. Akazawa

M, Halpern R, Riedel A, et al. Economic burden prior to COPD diagnosis: a

matched case-control study in United States. Respir

Med 2008;102:1744-52. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rmed.2008.07.009

30. Miravitles

M, Broisa M, Velasco M, et al. An

economic analysis of pharmacological treatment of COPD in Spain. Respir Med 2009;103:714-21.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rmed.2008.11.019

31. Nielsen R, Johannssen A, Bendiktsdottir B,

et al. Present and future costs of COPD in Iceland and Norway: results from the

BOLD study. Eur Respir J 2009;34:850-7. https://doi.org/10.1183/09031936.00166108

32. Del Negro RW, Tognella S, Tosatto R, et al.. Costs of COPD in Italy: the SIRIO study (social impact of

respiratory inÂtegrated outcomes). Respir Med 2008;102:92-101. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rmed.2007.08.001

33. Izquierdo

Alonso JL, de Miguel Diez J. Economic impact of

pulmonary drugs on direct costs on stable COPD. J COPD 2004;1:215-23.

https://doi.org/10.1081/COPD-120039809

34. Miller JD, Foster T,

Boulanger L, et al. Direct costs of COPD in the US: an analysis of medical expenditure

panel survey (MEPS) data. J COPD 2005;2:311-8.

https://doi.org/10.1080/15412550500218221

35. Gerdtham

UG, Andersson LF, Ericcson

A, et al. Factors affecting COPD-related costs: a multivariate analysis of a

Swedish COPD cohort. Eur J Health Econ 2009;10:217-26. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10198-008-0121-6

36. Saénz C, Sivori M, Blaho E, Sanfeliz N. Costos en la EPOC: Experiencia en el Hospital Dr.J.M.Ramos Mejia y

revisión de la literatura. Rev Arg Med Respir

2001:1:45-51.

37. Bakerly

ND. Cost analysis of an integrated care model in the management of acute

exacerbations of COPD. Chronic Respir Dis 2009;6:201-8. https://doi.org/10.1177/1479972309104279

38. Effing T, Kestejens

H, Van der Valk P, et al. Cost-effecÂtiveness of

self-treatment of exacerbations on the severity of exacerbations in patients

with COPD: the COPE II study. Thorax 2009;645:956-62.

https://doi.org/10.1136/ thx.2008.112243

39. Steuten

L, Lemmens K, Nieboer A, Vrijhoef H. IdentifiyÂing

potentially cost-effective chronic care programs for people with COPD. Int J COPD

2009;4:87-100. https://doi.org/10.2147/COPD.S3047

40. Puig Junoy J, Casas A,

Font-Planells J, et al. The impact of home hospitalization on healthcare costs

of exacerbations in COPD patients. Eur J Health Econ

2007; 8:325-32. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10198-006-0029-y

41. Schermer

TR, Saris CD, van den Bosch WJ, et al. ExacerbaÂtions and associated healthcare

cost in patients with COPD in general practice. Monaldi

Arch Chest Dis 2006;65:133- 40. https://doi.org/10.4081/monaldi.2006.558

42. Simoni-Wastila

L, Yang HW, Blancehtte CM, et al. HosÂpital and

emergency department utilization associated with treatment for COPD in a managed care Medicare utilization. Curr

Med Res Opin 2009;25:2729-35.

https:// doi.org/10.1185/03007990903267157

43. Simoens

S, Decramer M. Pharmacoeconomics

of the manageÂment of acute exacerbations of COPD. Exp

Pon PharmacothÂer 2007;8:633-48. https://doi.org/10.1517/14656566.8.5.633

44. Guarascio

AJ,Ray SM, Finch CK, Self

TH. The clinical and economic burden of COPD in USA. ClinEcon Outcomes Res 2013;5:235-45

45. Nomenclador del Ministerio de Salud del Gobierno de

la Ciudad Autónoma de Buenos Aires. Datos Personales. Junio 2021.

46. Manual Farmacéutico Kairos.

Junio 2021

47. Afolabi

AO, Watson B, Procter S, Wright AJ. The Cost to the Health

Service of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. Eur Resp

J 2000;16,31S:13.

48. Strassels

S, Smith D, Sullivan S, Mahajan P. The

costs of treating COPD in the United State. Chest 2001;119:334-52.

https://doi.org/10.1378/chest.119.2.344

49. Murray CJ, Atkinson C, Bhalla K, et al. The state of US health,1990-2010:

burden of diseases, injuries and risk factors. JAMA 2013;310:591-608. https://doi.org/10.1378/

chest.119.2.344

50. Trapero Bertran M, Oliva

Moreno J, y Grupos de Expertos GECA. Guía metodológica para la

estimación de los costes en asma. Luzan 5, SA

de Ediciones.2017.

51. Bilde

L, Svenning R, Dollerup J, Bække Borgeskov J, Lange P.

The cost of treating patients with COPD in Denmark - A population study of COPD

patients compared with non- COPD controls. Respir Med

1999;101:539-46. https://doi.

org/10.1016/j.rmed.2006.06.020

52. Hoogendoorn

M., Rutten-van Mölken

MP., Hoogenveen RT et al. A dynamic population model

of disease progression in COPD. Eur Respir J 2005;26:223-33. https://doi.org/10.1183/09031936.05.00122004

53. Dirección de Estadísticas en Salud del

Ministerio de Salud del Gobierno de la Ciudad Autónoma de Buenos Aires.

2021.

54. Montes de Oca M, Lopez

Varela V, Acuña A, et al. Guía de práctica clínica

de la EPOC ALAT 2014: Preguntas y respuestas. Arch Bronconeumol 2015;51:403-16.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arbres.2014.11.017

55. Miravitlles M, Soler

Cataluña JJ, Calle M, et al Guía español de la EPOC (GesEPOC) 2017. Arch BroncoÂneumol 2017;53:324-335.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arÂbres.2017.03.018

56. Vestbo

J, Anderson W, Coxson HO, et al. Evaluation of COPD

longitudinally to identify predictive surrogate end-points (ECLIPSE). Eur Respir J 2008;31:869–73. https://doi.org/10.1183/09031936.00111707

57. Soler-Cataluña

JJ, Martínez-García MA, Román Sánchez P, Salcedo

E, Navarro M, Ochando R. Severe acute exacerÂbations

and mortality in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Thorax 2005;60:925-31.

https://doi. org/10.1136/thx.2005.040527

58. Sivori M, Balanzat A, Casas JP, et al. Inhaloterapia:

RecoÂmendaciones para Argentina 2021. Medicina Buenos Aires 2021;81 (Supl II):1-32.

59. Usmani OS, Lavorini F, Marshall J, et al. Critical inhaler errors in asthma and COPD: a systematic review of

impact on health outcomes. Respir Res 2018;19: 10. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12931-017-0710-y

60. Sivori M, Fernández

R, Toibaro J,Velasquez

Gortaire E. Supervivencia en una cohorte de pacientes

con EPOC acorde a la clasificación GOLD 2017. Medicina Buenos Aires 2019;79:20-8.

61. Jimenez J, Sivori M. Evaluación de las comorbilidades por los

índices de Charlson y COTE en la EPOC y su

relación con la mortalidad. Revista Americana de Medicina RespiÂratoria

2022;22:3-9.