Autor : Calle, Catalina Alexandra1, Rosales, MarĂa Fernanda2, MacĂas Eddyn, RubĂ©n2

1Pulmonology Service, Axxis Hospital de Especialidades, Quito, Ecuador. 2Pulmonology Service, Hospital Carlos Andrade MarĂn, Quito, Ecuador.

https://doi.org./10.56538/ramr.VFNQ2915

Correspondencia : Catalina Calle E-mail: cata2906@hotmail.com

ABSTRACT

Introduction: idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis is a progressive, fatal disease characterÂized

by the findings of usual interstitial pneumonia in a high resolution tomography

or lung biopsy, or in a multidisciplinary discussion, also discarding other

etiologies such as connective tissue diseases or diseases associated with toxic

exposure.

The objective of this work was to

know the clinical characteristics, lung function and survival of the group of

patients diagnosed with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis who were evaluated at the

Interstitial Lung Disease Clinic of the Hospital Carlos Andrade Marín.

Materials and methods: retrospective, cross-sectional, observational study. The study

population consisted of patients diagnosed with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis who had been treated at the Interstitial Lung

Disease Clinic of the Hospital Carlos AnÂdrade Marín

between January, 2018 and February, 2020.

Results: 85.7% of the 35 patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis included in

the analysis were male. At the time of the diagnosis, the mean age was 69.7

years (SD [standard deviation]: 9.26, range: 38-87 years). 20% and 37.1% of

patients showed dyspnea grade 3 and 4, respectively. 60% had smoking history.

45.7% of the diagnoses were made

with a multidisciplinary clinical evaluation and high resolution computed axial

tomography.

Conclusions: we have reported the largest cohort of patients with idiopathic pulmoÂnary

fibrosis in Ecuador; our results identified similar populations with other

study groups where the high resolution computed tomography and

multidisciplinary analysis are the most used methods for the diagnosis.

Key words: Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis; Emphysema; Survival

RESUMEN

Introducción: la fibrosis pulmonar idiopática es una enfermedad progresiva y fatal

caracterizada por el hallazgo de neumonía intersticial usual en

tomografía de alta resolución o biopsia pulmonar, o en

discusión multidisciplinar y el descarte de otras etiologías como

enfermedades del tejido conectivo o exposicionales.

En cuanto a los objetivos de este trabajo, consisten en

conocer las características clíÂnicas, la función pulmonar

y la supervivencia del grupo de pacientes con diagnóstico de fibrosis

pulmonar idiopática evaluados en la clínica de intersticiales del

Hospital Carlos Andrade Marín.

Materiales y métodos: se trata de un estudio transversal, retrospectivo, observacioÂnal. La

población de estudio la constituyeron los pacientes con

diagnóstico de fibrosis pulmonar idiopática atendidos en la

clínica de intersticiales del Hospital Carlos AnÂdrade Marín

entre enero del 2018 y febrero del 2020.

Resultados: de 35 pacientes con fibrosis pulmonar idiopática incluidos para el

análiÂsis, el 85,7 % fueron del sexo masculino. Al momento del

diagnóstico, la edad promeÂdio fue de 69,7 años (DE: 9,26, Rango:

38-87 años). El 20 % y 37,1 % presentaron disnea de grado 3 y grado 4,

respectivamente. El 60 % presentaron antecedentes de tabaquismo.

El 45,7% de los diagnósticos se hicieron tanto con

evaluación clínica multidisciplinaria y tomografía axial

computarizada de alta resolución.

Conclusiones: hemos informado la mayor cohorte de fibrosis pulmonar idiopática en

el Ecuador, nuestros resultados han identificado poblaciones similares con

otros gruÂpos de estudio en los que la tomografía computarizada de alta

resolución y el análisis multidisciplinar son los métodos

más utilizados en el diagnóstico.

Palabras clave: Fibrosis pulmonar idiopática; Enfisema; Sobrevida

Received: 5/16/2022

Accepted: 8/23/2022

INTRODUCTION

Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis

(IPF) is a progresÂsive fibrosing interstitial

disease of unknown oriÂgin and poor prognosis, which ranges between 2 and 5

years of survival from time of diagnosis. It is the most common form of diffuse

interstitial lung disease (DILD), with a prevalence that oscillates between

twelve cases for every 100,000 women and 20 cases for every 100,000 men.1

This disease has an insidious

onset of sympÂtoms, with non-specific symptoms characterized by progressive

dyspnea, dry cough, Velcro-type tele-inspiratory

crackles and acropachy.1

The diagnosis is based on the

findings of usual interstitial pneumonia (UIP) in the high resolution computed

tomography (HRCT) or lung biopsy, or in a multidisciplinary discussion, also

discarding other etiologies, such as connecÂtive tissue diseases or diseases

associated with toxic exposure. Treatment is based on antifibrotic

agents, symptom management, and respiratory rehabilitation.2, 3

The first Latin American study

reported 761 ill patients diagnosed with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, where

Argentina and Mexico had the largest number of reported patients, 30.5% and

27.3%, respectively. 1.7% (n = 13) of the cases were from Ecuador.4

There are no DILD data in

Ecuador, so the naÂtional epidemiologic characterization is complex. Taking this

situation into account, the Hospital de Especialidad

Carlos Andrade Marín has created a DILD Clinic

of national reference, which was established in a multidisciplinary way, thus

allowÂing for the optimization of diagnosis, treatment, and registration processes.

Furthermore, access to antifibrotic treatment in the

country is limited, on the one hand, due to the little availability in

specialized care centers, and on the other hand, to the cost of these drugs.

This situation has a negative impact on survival, as shown by Cottin.5

The objective of this work was to

know the cliniÂcal characteristics, lung function and survival of the group of

patients diagnosed with IPF who were evaluated at the Interstitial Lung Disease

Clinic of the Hospital Carlos Andrade Marín.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Retrospective,

cross-sectional, observational study.The study population consisted of patients diagnosed with IPF who had been treated at the Interstitial Lung Disease

Clinic of the Hospital Carlos Andrade Marín

between January, 2018 and February, 2020.

Inclusion criteria comprised

adult patients who met the diagnostic criteria of the 2012 and 2018

ATS/ERS/JRS/ ALAT Guidelines for UIP, confirmed through tomography or lung

biopsy, in whom a secondary disease was discarded; also, the patients who had

been analyzed by a multidisciÂplinary committee, with complete medical records

were included. Exclusion criteria: pediatric patients, patients with other

secondary interstitial diseases, or neoplasia, and

those who didn’t do the lung function tests.

Variables under evaluation: age,

sex, tobacco use, gastroesophageal reflux disease,

pulmonary emphysema, family history of pulmonary fibrosis, clinical

characteristics (cough, grade of dyspnea, Velcro-type crackles, acropachy), respiratory functional characteristics, such as

forced vital capacity (FVC) in liters and expressed as percentage of predictive

value, diffusing capacity of the lungs for carbon monoxide (DLCO) as percentage

of predictive value, six-minute walk test, diagnostic method (HRCT, lung biopsy

or multidisciplinary discussion) and treatment.

In smokers, we calculated the

smoke index according to the number of packs consumed per year. The Charlson index was used to describe comorbidities.6

Statistical analysis

The descriptive analysis of

qualitative variables was carried out by calculating absolute and relative

frequencies. The results of quantitative variables were expressed as mean

values, since data distribution was normal according to the Kolmogórov-Smirnov

test.

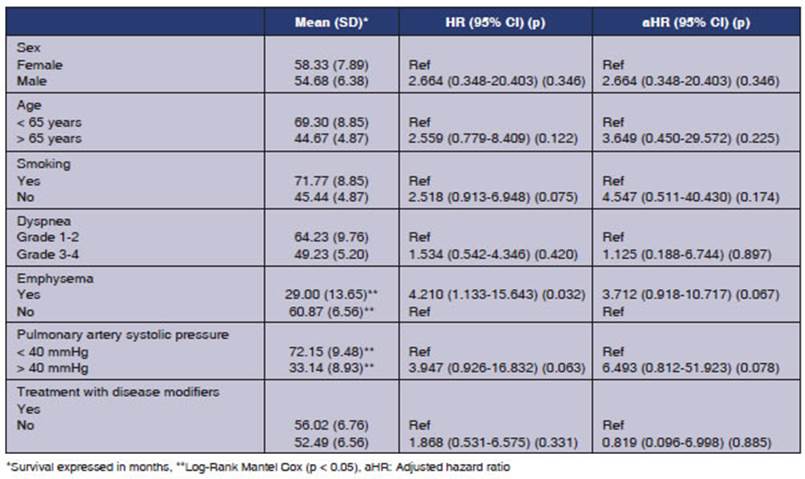

Factors taken into account for

the analysis of survival were: sex, age, smoking history, diagnosis of

pulmonary emphysema, Charlson index, grade of

dyspnea, systolic pressure of pulmonary artery and treatment with disease

modifiers. Survival was assessed in general and according to different factors

with Kaplan-Meier models; and the Log Rank Mantel Cox test was used to

establish differences between the survival gaps. The association of mortality

with risk factors was calculated through Cox Regression, obtaining the hazard

ratio values with their corresponding confidence intervals. Ap-value

of less than 0.05 was taken into account for statistical significance.

RESULTS

One patient was excluded from a

total of 36 poÂtentially eligible patients, due to incomplete lung function

tests.

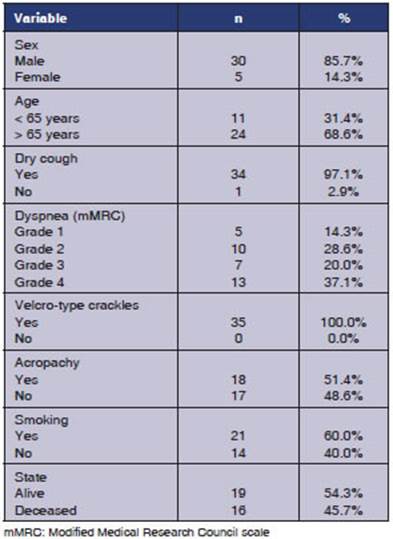

Table 1 shows the general

characteristics of the participants. 85.7% were male. At the time of the

diagnosis, the mean age was 69.7 years (SD: 9.26, range: 38-87 years). 20% and

37.1% of patients showed dyspnea grade 3 and 4, respectively. 60% had smoking

history. The mean amount of packs/ year among smokers was 9.1 (SD: 11.45).

45.7% died during the follow-up period.

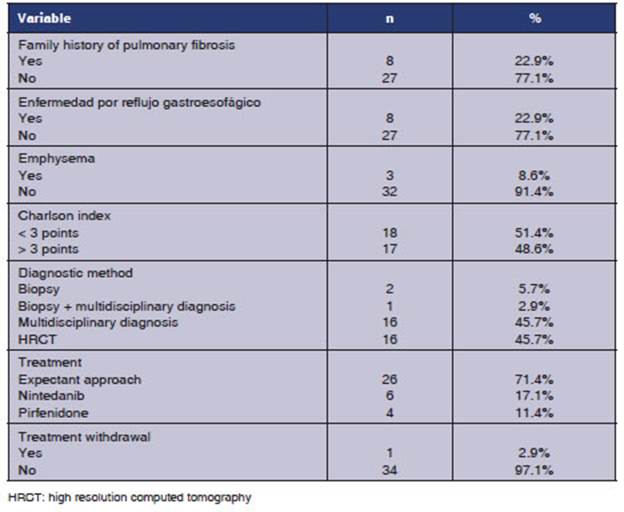

With regard to clinical history,

diagnosis and treatment, 22.9% and 8.6% were diagnosed with gastroesophageal

reflux and pulmonary emphyÂsema, respectively. 45.7% of the diagnoses were made

both through multidisciplinary clinical evaluation and HRCT. 28.6% received

treatment with disease-modifying drugs (17.1%, nintedanib

and 11,4%, pirfenidone)

(Table 2).

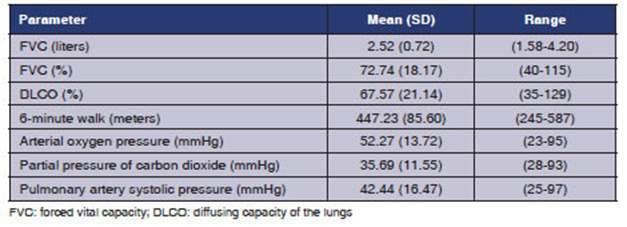

Table 3 shows the physiological

parameters evaluated in patients with IPF. The mean FVC obtained was 72.74%

(range: 40 to 115), whereas the DLCO was 67.57% (range: 35-129). The mean

distance travelled in the six-minute walk test was 447.23 m (SD: 85.60). The mean

value of arterial oxygen pressure (mmHg) was 52-27 (SD: 13.72) with the height

of Quito (2850 m). The mean value of the pulmonary artery systolic pressure was

42.44 mmHg (SD: 16.47).

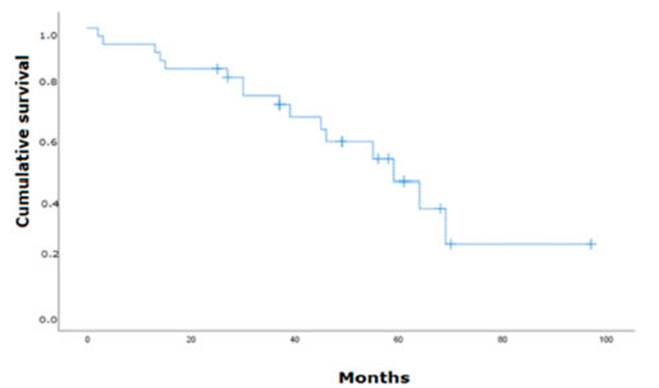

Mean survival of analyzed

patients was 57.24 months (95% CI: 45.07%-69.41%, SD: 6.21). When reaching 15

months of follow-up, around 15% (n = 5) of patients died. At 30 and 45

months, the cumulative mortality was 24% (n=8) and 36% (n=13). Until 65 months,

the cumulative mortality reached 63% (n=22)

(Figure 1).

Factors associated with survival

are explained in Table 4. The diagnosis of pulmonary emphyÂsema was

significantly associated with reduced survival time (HR: 4.210, 95% CI:

1.133-15.643, p = 0.032). Furthermore, patients older than 65 years (HR:

2.559, 95% CI: 0.779-8.409, p = 0.122), non-smokers (HR: 2.518

0.913-6.948, p = 0.075) with pulmonary hypertension (HR: 3.947, 95% CI:

0.926-16.832, p = 0.063) show clinically relevant mortality associations

(Table 3).

The widest gaps in mean survival values

accordÂing to the Kaplan-Meier analyses were observed in the following factors:

age (< 65 years: 69.3 months versus > 65 years: 44.67), smoking

(non-smokers: 45.44 months versus smokers: 71.77 months), diÂagnosis of

emphysema (Yes: 29 months versus No: 60.87 months) and value of pulmonary

artery sysÂtolic pressure (< 40 mmHg: 72.15 months versus > 40 mmHg: 33.14 months). Both the history of pulmonary

emphysema and the value of the pulÂmonary artery systolic pressure showed

statistical significance in the Log-Rank Mantel Cox Test (p = 0.019) and

(p = 0.046), respectively.

DISCUSSION

The evaluation of

this cohort of patients with IPF in a developing country such as Ecuador showed

the common characteristics of this disease as reÂgards its clinical and

functional parameters and diagnostic methods.

The mean age at the

time of the diagnosis was consistent with what is described in the literature,

as well as the higher prevalence of men.4,

5, 7

According to the

current ATS/ERS Guidelines, the lung biopsy is not necessary to establish the

IPF diagnosis in patients with tomographic features that confirm UIP, they should even be avoided due to the significant risk

of morbidity and mortality. Taking these reasoning and current guidelines into consideration,

in this study we observe a reduction of only 3% in the number of lung biopsies.

This percentage seems to be much lower than the one observed in other series.8

In any case, as it has been informed in the literature in the

past few years, there is a tendency to reduce the number of biopsies performed

in patients with this disease, as reported by the Korean cohort analyzed by

Sung Woo Moon.9

In the study of Wuyts, which analyzed 277 paÂtients diagnosed with IPF,

there was family history in 7% of patients, a low percentage compared to our

research. It would be interesting in the long run to analyze this population

genetically.10

The FVC was similar

to PANTHER-NAC, higher than ASCEND, and lower than NPULSIS-1 and INPULSIS-2.11-13

Furthermore, the DLCO exÂpressed in percentage and other

parameters of lung function, indicated less severe disease in our study group.14

Comorbid conditions

are increasingly being observed among patients with DILD. Data suggest a higher

prevalence of several comorbidities in paÂtients with IPF compared to the

general population. 48.6% of the study group has a Charlson

index score of > 3, representing lower values in comparison to those of the Cottin study, which reports 47.3% with a Charlson index score of > 5. This could be partly

explained by the younger age of our cohort of patients.4

Pulmonary hypertension and pulmonary emphysema are associated

with reduced survival time, as reported by the Mexican study of Mejía et al, with a HR for emphysema of 1.99

(1.12-3.53) p = 0.018, a PASP (pulmonary artery systolic pressure) of

more than 75 mmHg, and HR of 1.88 (1.01-3.48) p = 0.04 for pulmonary

hypertension.15

IPF is a disease with

a high mortality rate. Thanks to the ATS/ERS guidelines, a diagnostic method

has been standardized, thus allowing timely treatment. On the other hand,

global epiÂdemiological data have been obtained, with which significant

breakthrough has been made in the research of this disease.

Basing on that

information, it is time to estabÂlish in Ecuador the necessary measures to

allow a better diagnostic/therapeutic approach for lung interstitial diseases

and with that, the knowledge of the epidemiological impact they represent; to

that end we propose a national record of patients with DILD and in turn, the

creation of multidisÂciplinary committees for the purpose of directing

treatment access in the long run.

CONCLUSION

We have reported the

largest cohort of IPF patients in Ecuador. Our results have identified similar

popÂulations with other study groups where the HRCT and multidisciplinary

analysis are the most used methods for the diagnosis. Comorbidities, such as

pulmonary hypertension and emphysema show a reduction in survival time. Barely

29% of the population under evaluation received antifibrotic

treatment, so, apart from providing information on the characterization, we are

able to observe the natural course of the disease.

It is indispensable

to have well-organized and unified records of IPF patients so as to obtain

better results.

Conflicts of interest

The authors of this

work declare there isn’t any conflict of interest in relation to this

publication.

REFERENCES

1. Raghu G, Collard

H, Egan J, et al. An Official ATS/ERS/ JRS/ALAT Statement: Idiopathic Pulmonary

Fibrosis: Evidence-based Guidelines for Diagnosis and Management. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;183:788-824. https://doi.org/10.1164/rccm.2009-040GL

2. Raghu G, Rochwerg B, Zhang Y, et al. American Thoracic Society;

European Respiratory society; Japanese RespiratoÂry Society; Latin American

Thoracic Association. An official ATS/ERS/JRS/ALAT clinical practice guideline:

treatment of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. An update of the

2011 clinical practice guideline. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2015;192:e3-e19.

https://doi.org/10.1164/rccm.1925erratum

3. Raghu G, Remy-Jardin M, Myers JL, Richeldi L,

Ryerson CJ, Lederer DJ, et al.; American Thoracic

Society, European Respiratory Society, Japanese Respiratory Society, and Latin

American Thoracic Society. Diagnosis of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: an

official ATS/ERS/JRS/ ALAT clinical practice guideline. Am J Respir Crit

Care Med 2018;198: e44-e68.

4. Caro F, Buendía-Roldan I, Noriega-Aguirre L, et al, Latin

American Registry of Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis (REFIPI):Clinical

Characteristics, Evolution and TreatÂment. Arch Bronconeumol. 2022:S0300-2896(22)00329-5.

5. Cottin V, Spagnolo P, Bonniaud P, et al. Mortality and Respiratory-Related

Hospitalizations in Idiopathic PulÂmonary Fibrosis Not Treated With Antifibrotics. Front Med (Lausanne). 2021;8:802989.

https://doi.org/10.3389/ fmed.2021.802989

6. Charlson M, Carrozzinob D, Guidib J, Patierno C, CharlÂson Comorbidity Index: A Critical Review of Clinimetric Properties Psychother

Psychosom 2022;91:8-35. https://doi.org/10.1159/000521288

7. Gao Jing, Kalafatis D, Carlson L, et al.

Baseline

characterisÂtics and survival of patients of idiopathic pulmonary fbrosis: a longitudinal analysis of the Swedish IPF

Registry. Respir Res. 2021;22:40.

https://doi.org/10.1186/s12931-021-01634-x

8. Fisher J, Kolb M, Algamdi, et al. Baseline characteristics and comorbidities

in the CAnadian Registry for Pulmonary Fibrosis. BMC Pulm Med.

2019;19(1):223. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12890-019-0986-4

9. Moon S, Kim S,

Chung M, et al. Longitudinal Changes in Clinical Features, Management, and

Outcomes of IdioÂpathic Pulmonary Fibrosis. A Nationwide

Cohort Study. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2021;18:780-7. https://doi.org/10.1513/ AnnalsATS.202005-451OC

10. Wuyts W, Dahlqvist C, Slabbynck H, et al. Baseline clinical characteristics,

comorbidities and prescribed medication in a real-world population of patients

with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: the PROOF registry. BMJ Open Respir Res 2018; 5:e000331. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjresp-2018-000331

11. Raghu G, Anstrom KJ, King TE Jr, et al.

Prednisone, AzaÂthioprine, and N-Acetylcysteine for

Pulmonary Fibrosis. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:1968-77. https://doi.org/10.1056/ NEJMoa1113354

12. Richeldi L, du Bois RM, Raghu G, Azuma A, Brown KK, Costabel U, et al.; INPULSIS Trial Investigators. Efficacy and safety of nintedanib in

idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. N Engl J Med

2014;370:2071-82. https://doi.org/10.1056/

NEJMoa1402584

13. King T, Bradford

W, Castro-Bernardini S, et al. A

phase 3 trial of pirfenidone in patients with

idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. N Engl J Med.

2014;370:2083-92. https://doi.

org/10.1056/NEJMoa1402582

14. Behr J, Kreuter M, Hoeper MM, et al.

Management of paÂtients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis in clinical

practice: the INSIGHTS-IPF registry. Eur Respir J 2015;46:186-96.

https://doi.org/10.1183/09031936.00217614

15. Mejía M, Carrillo G, Rojas J, et

al. Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis and

Emphysema: Decreased Survival Associated With Severe Pulmonary Arterial

Hypertension. Chest. 2009;136:1-2.

https://doi.org/10.1378/chest.08-2306