Autor : Tomicic, Vinko1-2, Catalioti, Frank1, Mendoza, Sheyla3

1Coronary Care Unit. Hospital Regional Dr. Leonardo Guzmán, Antofagasta, Chile. 2Faculty of Medicine and Dentistry, Universidad de Antofagasta. 3Instituto Regional de Enfermedades Neoplásicas Norte, Trujillo, Perú.

https://doi.org./ramr.10.56538/GHKS7463

Correspondencia : Vinko Tomicic E-mail: vtomicic@gmail.com

ABSTRACT

A 20-year-old male with known

asthma diagnosis arrived at the Emergency DepartÂment of a hospital in his town

with history of dyspnea 1 day before admission. The paÂtient then became tachycardic, tachypneic and

cyanotic and received emergency intuÂbation. At the ICU (Intensive care Unit)

of the tertiary care general hospital, he showed severe bronchospasm, high

airway pressure during mechanical ventilation (MV) and severe hypoperfusion. He received crystalloids and norepinephrine

for resuscitation. On the third day, he developed subcutaneous emphysema,

pneumothorax and hyperÂcapnia with mixed acidosis. We

decided to use ultra-protective mechanical ventilaÂtion concomitant with Novalung®.

With this strategy, we were able to reduce airway pressures, iPEEP (intrinsic positive end-expiratory pressure) and

resistive mechanical power (MP) and improve hypercapnia

and acidosis. The patient was connected to Novalung® for ten days

and showed good evolution. Finally, he was extubated

and discharged from the ICU, and left the hospital in good condition.

Key words: Status asthmaticus, Ventilator-induced lung

injury, Extracorporeal circulation, Barotrauma

RESUMEN

Paciente varón de 20 años, con

diagnóstico de asma conocida, llegó al departamento de

emergencias de un hospital de su localidad con historia de disnea 1 d antes de

la admisión. Posteriormente, se torna taquicárdico,

taquipneico y cianótico, por lo que fue

intubado de emergencia. En la UCI del hospital general de tercer nivel,

presentó bronÂcoespasmo grave, presiones de vía aérea

elevadas durante la ventilación mecánica e hipoperfusión

grave. Recibió cristaloides y norepinefrina como resucitación. Al

tercer día, presentó enfisema subcutáneo,

neumotórax e hipercapnia con acidosis mixta. Se decidió utilizar

ventilación mecánica ultraprotectora

asociada con Novalung®. Con esta estrategia, logramos reducir

las presiones de la vía aérea, la PEEPi,

la potencia mecánica (PM) resistiva y mejorar la hipercapnia y la

acidosis. El paciente permaneció 10 d en Novalung® y

mostró buena evolución posterior. Finalmente, es extubado, dado de alta de la UCI y salió del

hospital en buenas condiciones.

Palabras clave: Estado asmático, Lesión pulmonar inducida por

ventilación mecánica, CircuÂlación extracorpórea, Barotrauma

Received: 05/23/2022

Accepted: 09/01/2022

INTRODUCTION

It is known that mechanical

ventilation (MV) produces per se injuries in the pulmonary fibrous

skeleton.1 This damage is associated with

lung compliance resistance, and the adjustment of tidal volume (TV), inspiratory

flow, PEEP level and respiratory rate (RR); the latter being related to the

amount of times the lung is subjected to an abnormal breathing pattern per unit

of time,2

generating an inflammatory process with positive feedback

(ventilator-induced lung injury vortex [VILI Vortex]).3,

4

The status asthmaticus

(SA) is developed with high airway pressures, where the resistance eleÂment is

the most important one. Even though the driving pressure (DP) is not a problem,

baroÂtrauma is also developed. In order to control the consequences of the

reduction in T V and RR (hypercapnia and respiratory acidosis), an extraÂcorporeal

CO2 remover is added (ECCO2R), which achieves

decarboxylation using low blood flow and low sweep flow.5-7

The mechanical power (MP) is

divided into its three components, and the magnitude of the “resistive power”

is described as being the one reÂsponsible for the MP. The reduction of the RR

and TV interrupts the dynamic hyperinflation cycle, thus reducing intrathoracic pressure, correcting acidosis, allowing for

the attenuation of hypoxic pulmonary vasoconstriction (HPV) and reducing the postload of the right ventricle.

We present the case of an

asthmatic patient with life-threatening risk who evolved with refractory hypercapnia, mixed acidosis with blood hypertenÂsion and

barotrauma, and was treated with arteÂriovenous ECCO2R (Novalung®).

CASE REPORT

20-year-old male with known

asthma who arrived at the Emergency Service (ES) of the regional hosÂpital of

Antofagasta; he had been referred from ToÂcopilla. He

complained of breathing difficulty one day before admission. Then he showed

tachypnea (30 rpm), with circumoral cyanosis and

respiratory muscle fatigue. Due to this condition, he received orotracheal intubation and was subjected to MV deeply

sedated and with neuromuscular blockade. He received norepinephrine due to the

hemodyÂnamic compromise.

He was admitted to the emergency

service with an APACHE II score of 11 points. MV was first delivered via

volume-controlled mode with a TV of 350 mL, RR 24, I:E

ratio = 1:3, PEEP 3 cmH2O

(intrinsic PEEP = 18 cmH2O)

and FiO2 of 50%. The patient

showed high inspiratory pressure (90 cmH2 O),

so nebulization with salbutamol and Berodual®

(fenoterol 0.25mg/mL + ipratropium

bromide 0.5 mg/mL) was intensified. The ausÂcultation revealed a bilateral

decrease in breath sounds, with generalized wheezing. Respiratory monitoring

showed a plateau pressure (Pplat) of 17 cmH2O and a static

compliance of 30 mL/ cmH2O.

Initial arterial blood gases: pH = 7.18, PCO2

= 50.5 mm/Hg, PaO2 = 89.3 mmHg, HCO3 = 18.2 mEq/L.

Negative PCR test for COVID-19.

At the ICU, the patient continued

with severe bronchospasm, desaturation up to 63% with inÂcreasing doses of

noradrenaline (from 0.06 μg/kg/ min to 0.2 μg/kg/min) and hypothermia tendency. Control tests showed lactic acidosis

(10.2 mMol/L) with pH of

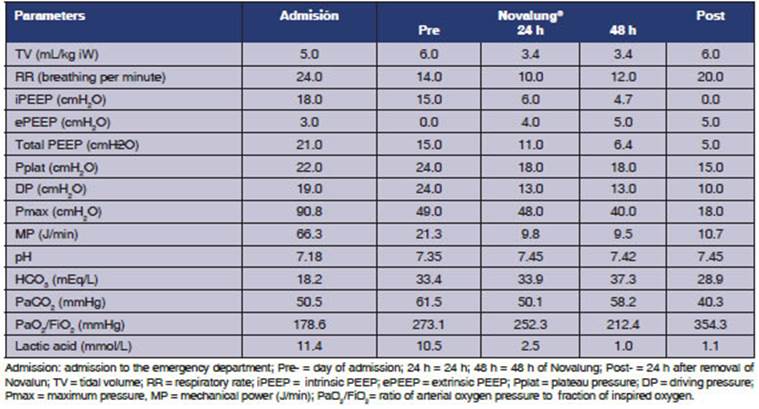

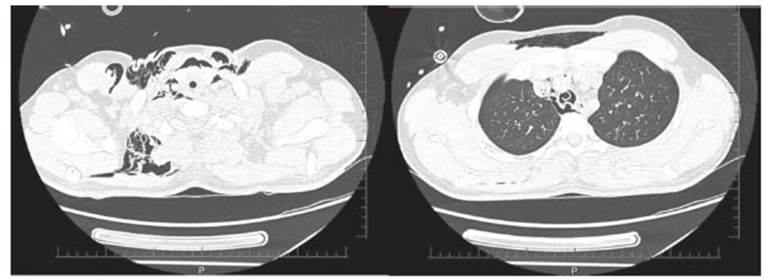

7.17 and HCO3 of 18 mEq/L. On the third day, the subject had palpable cervical

crackÂling sounds, and the chest scan showed cervical subcutaneous emphysema

and pneumothorax (Figure 1). Thus, a pleural tube was placed and the ventilatory schedule was modified. Methylprednisolone

boluses were included (500 mg x three times). The TV was reduced to 3.4 mL/kg

of predicted body weight, RR was reduced to 10 rpm, inspiratory time to 0.72 s,

minute ventilation (VE) to

2.6 L/min and the I:E ratio to 1:7, without PEEP. With

this pattern, the Pmax decreased to 48 cmH2O and the iPEEP reached 6 cmH2 O.

Due to the hypercapnia, it was associated with arteÂriovenous ECCO2R

(Novalung®).

Aminophylline was included. No fever or evidence of septic focus detected.

Once the patient was connected to

Novalung®,

we applied the volume-controlled mode with a TV of 300 ml and a RR of 10 rpm.

The Novalung® blood flow was maintained between

1.2 L/min and 1.6 L/min, and the sweep flow was adjusted between 6 L/min and 7

L/min. Table 1 shows the PaO2/FiO2 ratio, the PaCO2 and pH on the day the Novalung® device was connected.

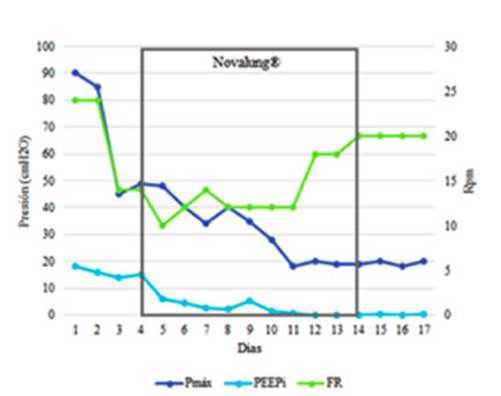

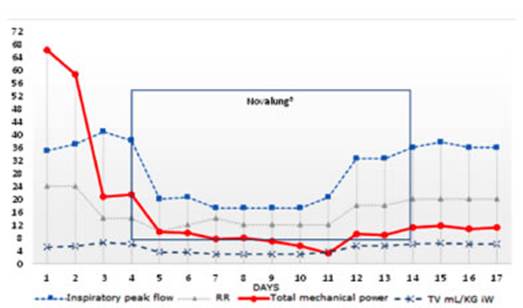

Twenty-four hours after being connected to Novalung®, the maximum pressure (Pmax) of the airways was reduced and oxygenation remained

unaffected. The most important modifications were a drop in the iPEEP and Pmax (Figure 1).

The patient remained connected to

Novalung® for ten days and showed good

evolution. 72 h after removing the Novalung® device, the patient was extubated. Ventilatory parameters

before extubaÂtion: Pplat =

15 cmH2O; DP = 10 cmH2O; Pmax

= 18 cmH2O and MP of 10

J/min, without iPEEP. Gasometric

parameters: pH = 7.44, PaCO2 =

39.6 mmHg, PaO2 =

71.9 mmHg. Give the patient’s stability, he was

discharged from the ICU 120 h after extubation,

having solved the bronchospasm.

DISCUSSION

The most important finding was to

identify the resistive mechanical power as the leading cause of barotrauma in a

patient with SA. A significant correlation was observed between the iPEEP and Pmax of the airway.

Both decreased drastically when we were able to reduce the RR and TV and extend

the expiratory time (I:E ratio = 1:7) after installing

the Novalung® device.

After introducing

this device, the RR could be reduced from 24 rpm to 10 rpm. Thus, the iPEEP was reduced from 15 cmH2 O

to 6 cmH2O. This change

reduced pulmonary hyperinflation and probably reduced the intrathoracic

pressure, imÂproving venous return and cardiac output; this was reflected in

the improvement of clinical perfusion, diuresis, and the correction of lactic

acid. Acidosis control should reduce the HPV and postload

of the right ventricle8 (Table 1).

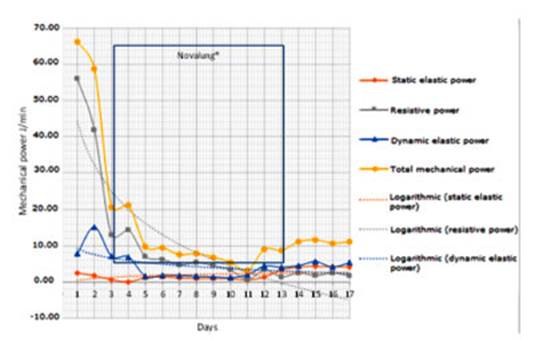

When we analyzed the

specific components of the MP, such as the static elastic power (associated

with PEEP), the dynamic elastic power (associÂated with TV) and the “resistive

power” (native airway), we observed that the drop in the MP was caused mainly

by the reduction of the resistive component, theoretically the most important

one in status asthmaticus. In our case, this

component reached more than 80% of the total MP on the first day (Figure 2).

When the exhalation

of gas is incomplete beÂcause the next inspiration begins before the lung is

completely empty, air trapping occurs and the expiratory time constant (τ) may

reach values near 0.9 s.9 For that reason, the expiratory time must be extended. The

reduction of the TV and RR also reduced the minute ventilation (VE), which is the main cause of

dynamic hyperinflation.9 Twenty-four hours after the

installation of the Novalung® device,

we observed the impact that the reduction in the RR and the TV had on the

“resistive power”, which decreased from 58 J/min to 14.6 J/min.

These patients often

show increased respiraÂtory effort and are dehydrated, and develop lactic

acidosis, worsening respiratory acidosis. All these elements were present in

our patient on admission, so he received crystalloids, norepinephrine and low

levels of PEEP (Table 1).

The MP considers all

the elements to be inÂcluded in the Otis equation. The DP and RR are the most

aggressive for the pulmonary fibrous skeleton.10 On the other hand, the peak flow is also an important variable for the

development of alveolar epithelial damage (Figure 3). ThereÂfore, the decrease

in the inspiratory flow avoids the disruption of the respiratory epithelium.

This phenomenon has been shown in an in vitro model of Tschumperlin.11

In our patient, as a consequence of the reduction in the RR, the

expiratory and inÂspiratory time could be simultaneously extended and so the

peak flow could be reduced.

The impact of the MP

has been studied in relaÂtion to the acute respiratory distress syndrome

(ARDS), but there aren’t enough studies that reÂlate it to asthmatic

decompensation.12-14 However, regardless of the

specific damage patterns, the dynamic elastic power (ARDS) or resistive power

(status asthmaticus), the mechanical power is inevitably transferred to the pulmonary fibrous skeleton in each

mechanical cycle.

The resistive component of the MP

must always be analyzed in patients with airway obstruction. When analyzing the

components separately, the resistive component (grey line) clearly stands out

as the main MP generator in this type of patients (Figure 2).

CONCLUSION

In short, when patients evolve

with high airway pressures, despite the existence of a suitable plateau

pressure, we must consider the resistive component of the MP as the origin of

barotrauma (bronchial obstruction). Through simple formulas we can predict the

impact of mechanical ventilator variables on asthmatic patients.10

The ECCO2R

systems are a safe tool to be associated with ultra-protective MV in severe

asthmatic patients.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that there is

no conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

1. Ranieri VM, Suter PM, Tortorella C et al. Effect of mechanical ventilation on inflammatory mediators in patients

with acute respiratory distress syndrome: a ranÂdomized controlled trial. JAMA

1999;282:54-61. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.282.1.54

2. Marini JJ, Rocco PR. Which

component of mechanical power is most important in causing VILI? Crit Care 2020;24:39.

https://doi.org/10.1186/s13054-020-2747-4

3. Marini JJ. How I optimize power

to avoid VILI. Crit Care 2019;23:326.

https://doi.org/10.1186/s13054-019-2638-8

4. Marini JJ, Gattinoni

L. Time Course of Evolving VentiÂlator-Induced Lung Injury: The “Shrinking Baby

Lung”. Crit Care Med. 2020;48:1203-9.

https://doi.org/10.1097/CCM.0000000000004416

5. Kukita

I, Okamoto K, Sato, T et al. Emergency extraÂcorporeal life support for

patients with near-fatal status asthmaticus. Am J Emerg Med 1997;15:566-9.

https://doi.org/10.1016/S0735-6757(97)90158-3

6. Lobaz

S, Carey M. Rescue of acute refractory hyperÂcapnia

and acidosis secondary to life-threatening asthÂma with extracorporeal carbon

dioxide removal (ECÂCO2R). J Intens Care Soc 2011;12:140-2.

https://doi.org/10.1177/175114371101200210

7. Augy

JL, Aissaoui N, Richards C

et al. Two years multiÂcenter multicenter

observational prospective, chort study on

extracorporeal CO2 removal

in a large metropolis area. J Intens Care Soc 2019;7:45.

https://doi.org/10.1186/s40560-019-0399-8

8. Peinado

VI, Santos S, Ramirez J, Rodriguez-Roisin R and Barberá JA. Response to hypoxia of pulmonary

arteries in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: an in vitro study. Eur Respir J. 2002;20:332. https://doi.org/10.1183/09031936.02.00282002

9. Tuxen

DV, Lane S. The effects of ventilatory

pattern on hyperinflation, airway pressures, and circulation in mechanical

ventilation of patients with severe air-flow obstruction. Am Rev Respir Dis 1987;136:872-9.

https://doi.org/10.1164/ajrccm/136.4.872

10. Costa ELV, Slutsky A, Brochard LJ, et al. Ventilatory Variables and Mechanical Power in Patients with

Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2021;204:303-11.

https://doi.org/10.1164/rccm.202009-3467OC

11. Tschumperlin

DJ, Margulies SS. Equibiaxial deformation-induced

injury of alveolar epithelial cells in vitro. Am J Physiol. 1998; 275:L1173-83.

https://doi.org/10.1152/ajplung.1998.275.6.L1173

12. Scharffenberg

M, Wittenstein J, Ran X, et al. Mechanical Power

Correlates with Lung Inflammation Assessed by Positron-Emission Tomography in

Experimental Acute Lung Injury in Pigs. Front Physiol. 2021;12:717266.

https://doi.org/10.3389/fphys.2021.717266

13. Demoule

A, Brochard L, Dres M et

al. How to ventilate obstructive and asthmatic patients.

Intens Care Med 2020;46:2436-49.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s00134-020-06291-0

14. Marini JJ (2011) Dynamic

hyperinflation and auto-positive end-expiratory pressure: lessons learned over

30 years. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 184:756–62.

https://doi.org/10.1164/rccm.201102-0226PP