Autor : De Vito, Eduardo L1,2,3, Tripodoro Vilma A.1

1Medical Research Institute Alfredo Lanari, Faculty of Medicine, University of Buenos Aires, Buenos Aires, Argentina. 2Centro del Parque, Respiratory Care Department, Buenos Aires, Argentina. 3Investigador Vinculado, NavarraBiomed, Centro de InvestigaciÃģn BiomÃĐdica, UPNA, EspaÃąa.

https://doi.org/10.56538/ramr.FFFU6290

Correspondencia : Eduardo Luis De Vito. E-mail: eldevito@gmail.com

ABSTRACT

The concept of breathlessness

emphasizes the multidimensional subjective nature of dyspnea with physical,

psychological, social, spiritual, and existential components. âTotal dyspneaâ

advocates a comprehensive, patient-oriented approach beyond the disease. The

term ârefractory dyspneaâ should be avoided; it implies a certain therapeutic

nihilism. For this reason, the term âchronic dyspnea syndromeâ was coined to

recognize treatment possibilities and raise awareness among patients,

physicians, healthcare teams, and researchers. People with advanced respiratory

disease and severe chronic dyspnea (and people who are close to them) have a

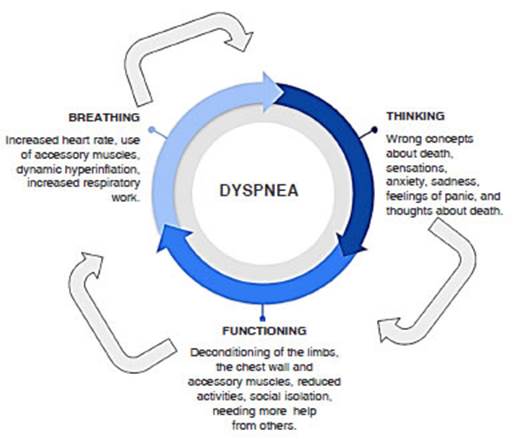

poor quality of life. The Breathing-Thinking- Functioning clinical-conceptual

model includes the three predominant cognitive and behavioral reactions that

worsen and maintain the symptom by causing vicious circles. Various instruments

are available for the comprehensive assessment of dyspnea that take into

account the sensory-perceptual experience, affective distress, and the impact

or burden of the symptoms. Breathlessness during the last weeks or days of life

can be called âterminal dyspnea.â It is a common symptom and one of the most

distressing in the latest phase of life of patients with cancer. Under these

circumstances, self-report may underestimate respiratory distress. The

Respiratory Distress Observation Scale is the first and only dyspnea assessment

instrument designed to evaluate its presence and intensity in patients who are

unable to communicate.

Key words: Breathlessness, Total dyspnea, Refractory dyspnea, Chronic

dyspnea syndrome, Terminal dyspnea

RESUMEN

El concepto de âdificultad para respirarâ enfatiza la

naturaleza subjetiva multidimensional de la disnea con componentes

físicos, psicológicos, sociales, espirituales y existenciaÂles.

La âdisnea totalâ aboga por un enfoque integral y centrado en el paciente

más allá de la enfermedad. La noción de âdisnea

refractariaâ debería ser evitada; implica cierto nihilismo

terapéutico. Por tal motivo, se acuñó el concepto de

âsíndrome de disnea crónicaâ para reconocer las posibilidades de

tratamiento y concientizar a los pacientes, los médicos, el equipo de

salud y los investigadores. Las personas que viven con enferÂmedades

respiratorias avanzadas y disnea crónica grave (y sus allegados) tienen

una mala calidad de vida. El modelo clínico-conceptual

ârespirando-pensando-funcionandoâ incluye las tres reacciones cognitivas y

conductuales predominantes que, al provocar círculos viciosos, empeoran

y mantienen el síntoma. Para la evaluación exhaustiva de la

disnea se dispone de diversos instrumentos que consideran la experiencia

sensorial-perceptiva, la angustia afectiva (distress) y el impacto o

carga de los síntomas. La dificultad para respirar durante las

últimas semanas o días de vida puede denominarse âdisnea

terminalâ. Es un síntoma frecuente y uno de los más angustiantes

en la última fase de la vida de pacientes con cáncer. En estas

circunstancias el autorreporte puede subestimar la dificultad respiratoria. La

Escala de Observación de Dificultad Respiratoria es el primer y

único instrumento de evaluación de la disnea destinado a evaluar

su presencia e intensidad en pacientes que no pueden comunicarse.

Palabras clave: Dificultad para respirar, Disnea total, Disnea refractaria, Síndrome

de disnea crónica, Disnea terminal

Received: 01/08/2023

Accepted: 05/02/2024

MULTIDIMENSIONAL APPROACH TO DYSPNEA

The concept of âbreathlessnessâ

is widely used in the literature related to palliative care, instead of the

biomedical term âdyspneaâ, to emphasize the daily experience from the patientâs

perspective.1 The multidimensional subjective nature of dysÂpnea goes beyond

merely the physical condition and highlights the importance of the psychologiÂcal,

social, spiritual, and existential components. Similar to the concept of âtotal

painâ described by Dame Cicely Saunders in the early 1960s, the concept of

âtotal dyspneaâ has been suggested, adÂvocating for a comprehensive and

patient-centered approach beyond the disease itself.2

If dyspnea persists despite

treatment of the underlying disease, it is sometimes referred to as ârefractory

dyspnea.â Since this term implies therapeutic nihilism, Johnson et al suggested

callÂing it âchronic dyspnea syndromeâ to acknowledge treatment possibilities

and raise awareness among patients, physicians, healthcare teams, and reÂsearchers.2 Chronic

dyspnea syndrome is described as the sensation of breathlessness that

persists despite receiving optimal treatment of the underlyÂing physiopathology

and causes disability.3-5 Like total

pain, total dyspnea encompasses multiple aspects and incorporates previously

neglected constructs, such as the suffering related to the meaning patients

assign to their symptoms. Total pain includes four domains: physical,

psychologiÂcal, interpersonal, and existential, and these are assessed from the

patientâs perspective. Dyspnea is subjected to a similar analysis.6

For more than a decade, the

respiratory sensaÂtion (neural activation resulting from the activaÂtion of

peripheral receptors) and perception (conÂscious and individual reaction to the

sensation) have been clearly differentiated.7

Consequently, the sensation of dyspnea

doesnât need to be related to identifiable physiological factors. Patientsâ exÂperiences

with dyspnea vary widely depending on factors such as ethnicity, experiences

with other diseases, and emotional state. Additionally, various psychological

and cultural factors can influence the reaction to a sensation. A stoic

individual may not perceive (or deny) respiratory discomfort. The context in

which the sensation occurs can also modify the perception of the sensory

experience.8-10

Anxiety, a particularly common

psychological factor that correlates with dyspnea, can exacerÂbate the symptom,

leading to a progressive spiral of increased dyspnea and higher distress.11,12 EpiÂsodes of

dyspnea can be predictable with known triggering factors, such as exertion,

emotions, comorbidities, or the external environment, or they can appear to be

unpredictable. Linde et al stated that many seemingly inexplicable episodes

were known to have been driven by fear or panic when evaluated in depth.13

IMPACT OF DYSPNEA

Dyspnea often triggers panic,

fear, anxiety, deÂpression, hopelessness, a sense of loss of control, and a

feeling of imminent death.14,15 It also affects daily and social functions,

leading to dependency and loss of roles. This symptom is one of the six

parameters used in the Palliative Prognostic Score, which predicts the 30-day

survival of patients in palliative care.16

A qualitative study illustrated

the meaning of the dyspnea experience in patients with cancer, COPD (chronic

obstructive pulmonary disease), heart failure, and amyotrophic lateral

sclerosis (ALS):17

â For individuals with cancer,

dyspnea serves not only as a sign of the presence of cancer but also as a

reminder of mortality, even in the face of treatment optimism.

â In people with COPD, dyspnea is

perceived as self-inflicted due to lifelong smoking.

â For those with heart failure,

dyspnea is associÂated with functional limitations and contributes to the

negative effects of other symptoms.

â In individuals with ALS, dyspnea

is related to mechanisms that are essential for living.

DYSPNEA AND QUALITY OF LIFE

People with advanced respiratory

diseases and severe chronic dyspnea (and the people close to them) have a poor

quality of life.1,17 Chronic dyspnea is an incapacitating symptom,

and acute episodes are terrifying to experience and observe. Many millions of

people around the world live with advanced respiratory diseases, such as COPD

and interstitial lung disease (ILD).18

These individuals arenât receiving the

palliative care they need to have the best possible quality of life.

These prevalent diseases, as well

as other less common ones, can progress rapidly or have a more chronic course,

and younger patients may be awaitÂing a lung transplant. However, in all cases,

as the disease progresses, the patient becomes very symptomatic and is unlikely

to improve despite maximum treatment of the underlying disease.

Although there is no comparable

infrastructure for providing palliative care in non-oncological respiratory medicine,

it is recognized that the deficit in symptom control and psychosocial supÂport

leads to a poorer quality of life for patients not only with advanced

respiratory diseases but also in the general population, and it is likely to

have a negative effect on medical outcomes.19

ACUTE AND CHRONIC DYSPNEA AND PERSON-CENTERED CARE

Generally, more attention is

given to the treatÂment of acute dyspnea than to chronic dyspnea.

Therefore, it is the responsibility of every physician to provide the best person-centered

care possible, ensuring the use of all available resources and knowledge.19

The term person-centered care,

recognized as a hallmark of excellence in care, also encompasses the choice of

specific treatments targeted at the disease, and provides a foundation for

ensuring that patients receive individualized treatment, and that their

symptoms and other concerns are identified. Healthcare professionals must play

an active role in promoting quality of life as part of excellent medical care.

DYSPNEA IN TERMINAL RESPIRATORY DISEASE

The cardinal symptoms of advanced

respiratory disease are persistent dyspnea, fatigue, and cough, sometimes

referred to as the respiratory triad.20, 21 All these symptoms

can be invisible at rest, so they need to be actively elicited to detect them.

Scientific evidence for symptomatic treatments has improved in recent years;

not using them in specialized respiratory care services should be considered

inexcusable.

Other factors that greatly affect

the outcomes and quality of life are outside the sphere of clinical influence,

for example: financial anxiety, housing loss, lack of food, difficulty

obtaining social asÂsistance, concern about the continuity of health benefits,

social isolation, caregiver burnout, and breakdowns in family relationships.

Being outside the sphere of clinical influence does not mean they should be

ignored.

THE EXISTENTIAL MEANING OF DYSPNEA

The spiritual repercussions of

dyspnea can be strong. Just like pain, patients may attribute a variety of

meanings to dyspnea, ranging from Godâs punishment to a divine gift.

Additionally, the patientâs religious or metaphysical beliefs can influence the

extent of their suffering.22-24 The secondary physiological and behavioral responses to

dyspnea should be considered in the evaluaÂtion process. This concept has been

subjected to experimental testing, supporting the hypothesis that the multiple

dimensions or components can be measured as different entities. Some studies

have demonstrated the existence of a separable âaffective dimensionâ

(i.e., distress and emotional impact).25

SUBJECTIVE INDIVIDUAL EXPERIENCE

Dyspnea affects people in

different ways and across different dimensions, which is well demonstrated by

the Breathing, Thinking, Functioning clinical model.21

This model conceptualizes the three preÂdominant cognitive and

behavioral reactions to dyspnea that, by creating vicious cycles, worsen and

sustain the symptom (Figure 1).

Breathing domain: shortness of breath asÂsociated with dysfunctional breathing patterns,

increased respiratory rate, the need to use accesÂsory muscles, and dynamic

hyperinflation, leading to inefficient breathing and increased respiratory

work.

Thinking

domain: misconceptions about the nature of dyspnea, such as

its cause, and previous experiences and memories that profoundly impact the

current experience. This negative

cognition and memories can cause anxiety, sadness, panic, and thoughts about

death.

Functioning domain: individuals suffering from dyspnea often reduce their physical activity

to avoid the sensation of breathlessness, leading to social isolation,

increased dependence on others, and general deconditioning.

FAMILY IMPACT OF DYSPNEA

The dyspnea experienced by

patients also afÂfects informal caregivers (family and friends). However, their

burden and anxieties are often overlooked and the existence of those feelings

is normalized.28

Caregivers of dyspnea patients

perform many invisible caregiving tasks, such as hygiene, dressÂing, symptom

control, and administering medicaÂtion and oxygen, in addition to all the

household chores.29 They also provide emotional support not only during the day

but also through diffiÂcult nights. They remain awake monitoring the patientâs

breathing, and checking if they are still alive. Thus, it is not surprising for

caregivers to report poor quality sleep, similar to people working shifts and

mothers of young children.

Therefore, when treating patients

with dyspnea, it is also necessary to focus on caregivers and their needs,

providing them with education, support, and resources, just like for the

patients. Caregivers should be encouraged to also take care of their own

health, both physical and emotional.

EVALUATION AND IDENTIFICATION OF THE CAUSES OF DYSPNEA

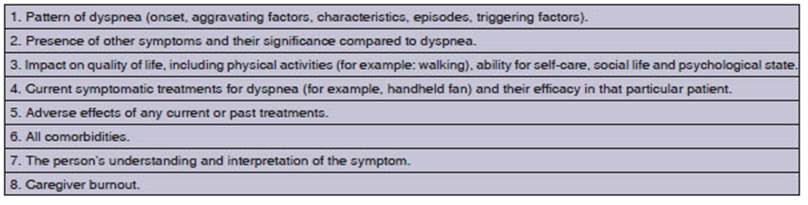

The assessment of dyspnea must

include the paÂtientâs subjective experience; therefore, the self-report of the

symptom is essential. This should include the sensory component with its

intensity and severity, the emotional burden reflected in the discomfort caused

by dyspnea, and the impact on the patientâs daily life.

Currently, there is no

universally accepted measure of health outcomes in clinical or research

settings, which poses a clear barrier to routine clinical evaluation and

follow-up of dyspnea.

The evaluation of a patient

should also include a physical examination with vital signs and a cardioÂpulmonary

exam. Although additional diagnostic tests may be important to identify any

treatable cause of dyspnea, it should be noted that more obÂjective

evaluations, such as respiratory rate, blood gas analysis, or lung function

tests do not meaÂsure dyspnea and only moderately correlate with the patientâs

subjective experience. For optimal management of dyspnea, treating the

underlying disease and addressing reversible symptoms are the first step.

INSTRUMENTS FOR MEASURING DYSPNEA

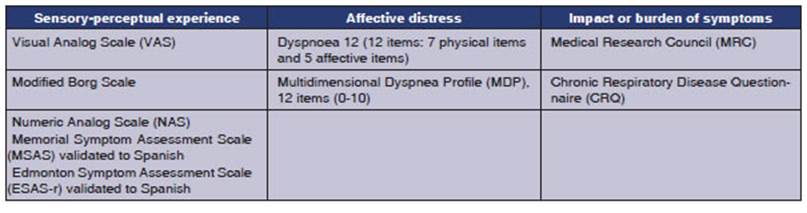

For a comprehensive evaluation of

its multidimenÂsionality, an instrument must reflect each patientâs subjective

sensory experience, provide an objective measurement of dyspnea, and facilitate

the effecÂtive communication with the healthcare team.31

There are three domains of dyspnea

measurement proposed by the American Thoracic Society in 2012 and 2013.11,12

1. Sensory-perceptual experience: this inÂcludes the ratings of symptom intensity, frequency, duration,

and sensory quality. The intensity of dysÂpnea can be assessed using a Visual

Analog Scale (VAS), the Borg Scale32,

Likert-type ratings, or the Numeric Analog Scale (NAS). Dyspnea is also includÂed

in validated Spanish multidimensional assessment tools, such as the Memorial

Symptom Assessment Scale and the Edmonton Symptom Assessment Scale (ESAS-r

validated in Spanish).33,34. For sensory qualÂity, Simon et al35

reported 15 descriptors of dyspnea used by patients in eight groups (rapid,

exhalation, shallow, effort, choking, hunger, tight, and heavy). The authors

suggested possible associations of the descriptors with specific conditions

causing dyspnea, but a subsequent study by Wilcock et

al36 could not

demonstrate the robustness of these descriptors in helping with the diagnosis

when applied to patients with cancer and cardiopulmonary diseases.37

2. Affective distress: this can refer to immediÂate distress or the distress that patients feel

when they understand the meaning or consequences of their symptom. Discomfort

can be rated as a single item, as in the case of dyspnea intensity. Scales with

multiple items, such as the one for dyspnea in cancer, assess emotional

responses, including anxiety.38,39

Two validated measures, Dyspnoea

12 and the Multidimensional Dyspnea Profile (MDP), are suitable for

use in both clinical and research settings and are brief enough for assessment

and follow-up.38-40

Dyspnoea 12 is a 12-item measure of dyspnea severity with 7 physical

items and 5 affective items not related to physical activity. Response options

are: none (0), mild (1), moderate (2), or severe (3). The time period refers to

âthese days.â40, 41

The MDP is also a

12-item scale that uses scores (0-10). Seven items refer to overall intensity,

unpleasantness, and other qualitative sensory descriptions of dyspnea

(increased respiratory muscle work, chest tightness, air hunger, breathÂing a

lot, requiring mental effort), and five rate the emotional responses to dyspnea

(depression, anxiety, frustration, anger, and fear).42,43

3. Impact or burden

of symptoms: this includes the

effect of dyspnea on behavior, funcÂtions, quality of life, or health status.

The Medical Research Council (MRC) scale provides a unidiÂmensional rating of

disability,44-46 while the

Chronic Respiratory Disease Questionnaire (CRQ) is a multidimensional scale

used for the assessment of functionality.47-49

The MRC scale

evaluates the consequences of dyspnea in relation to functional limitations. It

is particularly useful if dyspnea is the only symptom experienced by the

patient but is too insensitive to detect subtle changes after an intervention.8

Several quality of life scales have been validated for use in cancer or

specifically for lung cancer and chronic lung diseases, such as the CRQ47,48,50,51, EuroQol 5D, FACT-L52,

QLQ-C15-PAL53-55 and QLQ-LC13.56,57 Table 2 summarizes

the dyspnea assessment instruments and their main domains.

Currently, there are

more than 50 scales for measuring dyspnea, covering several dimensions and

different diseases.11 However, there is no unified measurement tool

for clinical use in the palliative care setting. It may be possible to comÂbine

the assessment of dyspnea intensity with its impact on the patientâs quality of

life.58 The NAS, the Modified Borg Scale, the CRQ dyspnea scale59,

the ALS Assessment Scale (based on the CRQ)60 and the Cancer Dyspnea

Scale seem to be the most suitable for the palliative care settings.61

Dyspnea can also be

measured in terms of exÂercise tolerance. Several instruments have been

validated in advanced disease, namely, the Shuttle Walking Test62,

the Reading Numbers Aloud Test63, and the Upper Limbs Test.64

Unfortunately, the fact that these tests are slow and expensive curÂrently

limits their applicability in the clinical setting.58

EVALUATION OF DYSPNEA CRISES

During crises, the

patient is likely to experience an increase in intensity, distress, and fear.12

Initially, dyspnea is often a component of several

symptoms, including depression and anxiety. Self-report is the most valid and

reliable method for assessing the patientâs experience, symptom progression,

and response to treatment.

The simplest

self-report is a dichotomous yes or no response to the question, âAre you

short of breath?â However, yes or no responses are unlikely to help with

palliative care, so the use of some rating of dyspnea intensity is expected. At

least a standardized measure is recommended, such as the 0-10 Numerical Rating

Scale, augmented by the evaluation of the patientâs subjective experience of

distress and discomfort alongside the rating of dyspnea intensity.

TERMINAL DYSPNEA

Dyspnea suffered by

patients during the last weeks or days of their life can be called âterminal

dyspnea.â65 Timely assessment and proactive management of

dyspnea in these patients are of vital importance. This symptom has unique

cliniÂcal characteristics: it tends to worsen rapidly over days or hours as

death approaches, even despite symptom control measures. The family is also

deeply affected, experiencing anxiety, uncertainty, helplessness, and

inability. An assessment of the family-caregiver, the need for information, the

desired level of participation in care, and home resources will support

caregivers and integrate them into the healthcare team.

International

guidelines have recently recogÂnized that dyspnea is common and one of the most

distressing symptoms in the final stages of life for cancer patients66

and that patients have difficulty self-reporting the symptom. Since self-report

is the gold standard for assessing dyspnea, there is a need to seek

alternatives for this group of patients.

In clinical practice,

healthcare teams conduct indirect assessments of symptom severity. HowÂever,

the accuracy of these subjective assessments may be poor. Studies conducted in

advanced cancer populations and in intensive care units show that indirect

assessments by physicians and nurses are significantly lower and poorly related

to patient self-report. Given the fact that symptom severity assessments

influence treatment decisions, a betÂter method for assessing dyspnea in

patients who cannot express themselves is necessary.

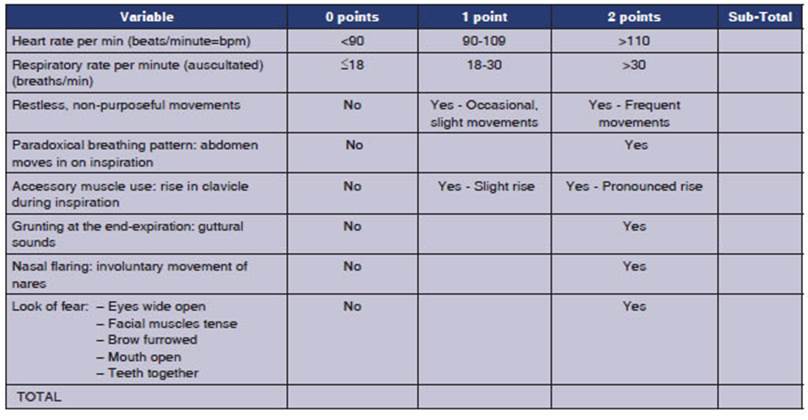

The Respiratory

Distress Observation Scale (RDOS) is an ordinal 8-item scale designed to

measure the presence and intensity of breathlessÂness in adults. This scale was

developed from a bio-behavioral framework by Campbell.67,68

It is the first and only dyspnea assessment tool developed so far to evaluate

its presence and intensity in paÂtients who are unable to communicate.68-70

There are two modifications of the RDOS available for intensive care patients:

the IC-RDOS (Intensive Care Respiratory Distress Observation Scale)68,69,71

and the MV-RDOS (Mechanical Ventilation RespiÂratory Distress Observation Scale).72

The RDOS demonstrates

strong inter-rater reliÂability, convergent validity, and divergent validity,

suggesting its reliability and validity as an assessÂment tool for palliative

care patients.

Most importantly, it

shows clinical utility by demonstrating good discriminative properties in

detecting patients with moderate and severe dyspnea. A new RDOS cutoff point of

≥ 3 has been proposed for therapeutic intervention, with a sensitivity of

68% and a specificity of 77% for distinguishing between moderate to severe

distress versus none (positive predictive value: 0.85 and negative predictive

value: 0.61).69,70 Table 3 shows the objective variables considered

by the RDOS and the corresponding scores.

Seven patients (63.6 %) completed

treatment, three patients (27 %) discontinued treatment, and one patient (9 %)

passed away during the treatment. In terms of follow-up, one patient showed

rifampicin resistance (patient with conÂcurrent lung involvement), and another

patient (9 %) experienced reversible hepatotoxicity due to pyrazinamide.

The evaluation of the

use of accessory muscles is based on the observation of the clavicle elevaÂtion

during inspiration. It does not refer to the palpation of accessory muscles

such as the scalene, intercostals, sternocleidomastoid, or the contracÂtion of

the abdominal muscles during expiration. Clavicle elevation somewhat reflects

the activation of the upper thoracic and neck muscles and is an easy-to-

identify sign.

The prevalence and

severity of dyspnea increase at the end stages of life. Many of the patients in

that situation have difficulty reporting their symptoms. Dyspnea is a symptom,

only the perÂson experiencing it can say that they are short of breath. Certain

operational aspects of the use of Table 3 should be emphasized:

â The RDOS is used in

adults and is not a subÂstitute for what the patient reports, as long as they

can express it.

â The scale should

not be used if the patient is paralyzed with a neuromuscular blocker and is not

valid in cases of bulbar ALS or quadriplegia.

â Respiratory and

heart rate can be measured during auscultation if necessary.

â Grunting can be

audible even in intubated paÂtients through auscultation.69

The RDOS is promising

and has clinical utilÂity as an observational dyspnea assessment tool. Further

studies in less communicative patients are needed to determine clinical utility

and the generalizability of the results.

CONCLUSIONS AND FUTURE APPROACH

It is not possible to

address a person with dyspnea without considering its multidimensional subjecÂtive

nature, with its physical, psychological, social, spiritual, and existential

components. The term âtotal dyspneaâ encompasses these components. The term

ârefractory dyspneaâ should be avoided and replaced by âchronic dyspnea

syndromeâ in order to recognize treatment possibilities and raise awareness

among patients, physicians, healthcare teams, and researchers.

â People living with advanced

respiratory diseases and severe chronic dyspnea (and the people close to them)

have a poor quality of life.

â The

Breathing-Thinking-Functioning clinical model includes the three predominant

cognitive and behavioral reactions against dyspnea that worsen and maintain the

symptom.

â There are various instruments

available for the comprehensive assessment of dyspnea as a multidimensional

symptom. These instruments propose considering the sensory-perceptual

experience, affective distress, and the impact or burden of the symptoms.

â Dyspnea suffered by patients

during the last weeks or days of their life can be called âtermiÂnal dyspnea.â

It is a common symptom and one of the most distressing in the latest phase of

life of patients with cancer.

â While the self-report of the

sensation of breathÂlessness is essential, some patients may not be able to

express it, and it may be underestimated. The Respiratory Distress Observation

Scale is the first and only dyspnea assessment instruÂment used to evaluate its

presence and intensity in patients who are unable to communicate.

A better understanding of the

brain processes underlying the perception of dyspnea will lead to new

therapeutic approaches aimed at improving the quality of life for a very large

group of patients.

REFERENCES

1. Booth S, Johnson MJ. Improving the quality of life of people with advanced respiratory

disease and severe breathlessness. Breathe (Sheff) 2019;15:198-215. https://doi.org/10.1183/20734735.0200-2019

2. Johnson MJ, Currow DC, Booth

S. Prevalence and assessÂment of breathlessness in the clinical setting. Expert

Rev Respir Med 2014;8:151-61.

https://doi.org/10.1586/17476348.2014.879530

3. Carel H, Macnaughton J, Dodd

J. Invisible sufferÂing: breathlessness in and beyond the clinic. Lancet Respir

Med 2015;3:278-9. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2213-2600(15)00115-0

4. Marjolein G, Higginson IJ.

Access to Services for PaÂtients with Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease:

The Invisibility of Breathlessness. J Pain Symptom ManÂage 2008;36:451-60. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpainsymÂman.2007.11.008.

5. Morélot-Panzini C,

Adler D, Aguilaniu B, et al. DysÂpnoea working group of the

Société de Pneumologie de Langue Française. Breathlessness

despite optimal pathophysiological treatment: on the relevance of beÂing

chronic. Eur Respir J 2017;50:1701159.

https://doi.org/10.1183/13993003.01159-2017.

6. Langford RM. Pain:

nonmalignant disease for current opinion in supportive and palliative care.

Curr Opin SupÂport Palliat Care 2008;2:114-5.

https://doi.org/10.1097/SPC.0b013e32830139d5.

7. Guz A. Brain, breathing and

breathlessness. Respir Physiol 1997;109:197-04.

https://doi.org/10.1016/S0034- 5687(97)00050-9

8. Mahler DA, OâDonnell DE.

Dyspnea: Mechanisms, MeaÂsurement, and Management, Third Edition. CRC Press, 2014. https://doi.org/10.1201/b16363

9. Mahler, Donald (1991). Dyspnea. Medicine & SciÂence in Sports & Exercise

1991;23:1322.

https://doi.org/10.1249/00005768-199111000-00027.

10. Mahler DA. Understanding

mechanisms and documentÂing plausibility of palliative interventions for

dyspnea. Curr Opin Support Palliat Care 2011;5:71-6.

https://doi.org/10.1097/SPC.0b013e328345bc84

11. Parshall MB, Schwartzstein

RM, Adams L, et al. An offiÂcial American Thoracic Society statement: update on

the mechanisms, assessment, and management of dyspnea. Am J Respir Crit Care

Med 2012;185:435-52.

https://doi.org/10.1164/rccm.201111-2042ST

12. Mularski RA, Reinke LF,

Carrieri-Kohlman V, et al. An OfÂficial American Thoracic Society Workshop

Report: AssessÂment and Palliative Management of Dyspnea Crisis. Ann Am Thorac

Soc 2013;10:S98-S106.

https://doi.org/10.1513/AnnalsATS.201306-169ST

13. Linde P, Hanke G, Voltz R,

Simon ST. Unpredictable episodic breathlessness in patients with advanced

chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and lung cancer: a qualitaÂtive study.

Support Care Cancer 2018;26:1097-104.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-017-3928-9.

14. Gysels M, Bausewein C,

Higginson IJ. Experiences of breathlessness: A systematic review of the

qualitative literature. Palliat Support Care 2007;5:281-302.

https://doi.org/10.1017/S1478951507000454

15. Simon ST, Higginson IJ,

Benalia H, et al. Episodes of breathÂlessness: Types and patterns â a

qualitative study exploring experiences of patients with advanced diseases. Palliat Med 2013;27:524-32.

https://doi.org/10.1177/0269216313480255

16. Pirovano M, Maltoni M, Nanni O, et al. A New Palliative Prognostic Score. J Pain Symptom Manage 1999;17:231-9.

https://doi.org/10.1016/S0885-3924(98)00145-6

17. Gysels M, Higginson IJ.

Access to services for patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: the

invisibility of breathlessness. J Pain Symptom Manage 2008;36:451-60.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2007.11.008

18. World Health Organization. Chronic respiratory diseases. https://www.who.int/health-topics/chronic-respiratory-diseases#tab=tab_1.

2023.

19. Currow DC, Dal Grande E, Ferreira D, et al. Chronic breathlessness associated with poorer physical and mental

health-related quality of life (SF-12) across all adult age groups. Thorax 2017;72:1151-3. https://doi.org/10.1136/thoraxjnl-2016-209908

20. Yorke J, Lloyd-Williams M,

Smith J, et al. Management of the respiratory distress symptom cluster in lung

cancer: a randomized controlled feasibility trial. Support Care Cancer 2015;23:3373-84. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-015-2810-x

21. Yorke J, Johnson MJ, Punnett G, et al. Respiratory distress symptom intervention

for non-pharmacological manageÂment of the lung cancer

breathlessnessâcoughâfatigue symptom cluster: randomised controlled trial. BMJ

SupÂport Palliat Care 2022;spcareâ2022.

https://doi.org/10.1136/spcare-2022-003924

22. Langford RM. Pain:

nonmalignant disease for current opinion in supportive and palliative care.

Curr Opin SupÂport Palliat Care 2008;2:114-5. https://doi.org/10.1097/SPC.0b013e32830139d5120

23. Booth S. Science Supporting

the Art of Medicine: ImÂproving the Management of Breathlessness. Palliat Med

2013;27:483-5.

https://doi.org/10.1177/0269216313488490.

24. Hutchinson, A. Patient and

carer experience of breathÂlessness. In C. Bausewein, D. C. Currow, & M. J.

JohnÂson (Eds.), Palliative Care in Respiratory Disease 2016 (102-110). European Respiratory Society. https://doi.org/10.1183/2312508X.10011615

25. Lansing RW, Gracely RH,

Banzett RB. The multiple dimensions of dyspnea: review and hypotheses. Respir

Physiol Neurobiol 2009;167:53-60.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resp.2008.07.012

26. Spathis A, Booth S, Moffat C,

et al. The Breathing, ThinkÂing, Functioning clinical model: a proposal to

facilitate evidence-based breathlessness management in chronic respiratory

disease. NPJ Prim Care Respir Med 2017;27:27.

https://doi.org/10.1038/s41533-017-0024-z.

27. Spathis A, Burkin J, Moffat

C, et al. Cutting through complexity: the Breathing,

Thinking, Functioning cliniÂcal model is an educational tool that facilitates

chronic breathlessness management. NPJ Prim Care Respir Med

2021;31:25.

https://doi.org/10.1038/s41533-021-00237-9.

28. Veloso VI, Tripodoro VA. Caregivers burden in palliaÂtive care patients: a problem to tackle.

Curr Opin SupÂport Palliat Care 2016;10:330-5.

https://doi.org/10.1097/SPC.0000000000000239.

29. Farquhar M. Supporting

informal carers. Palliative Care in Respiratory Disease.

Eur Respir Monogr 2016;73:51-69. https://doi.org/10.1183/2312508X.10011315

30. Bruera E, Higginson EJ, von

Gunten CF, Morita T. TextÂbook of Palliative Medicine and Supportive Care 2021,

CRC Press, https://doi.org/10.1201/9780429275524.

31. Chan K-S, Tse DMW, Sham MMK. Dyspnoea and other respiratory symptoms in palliative care. Oxford Textbook of Palliative Medicine 2015;421-34.

https://doi.org/10.1093/med/9780199656097.003.0082

32. Borg GAV. Psychophysical

bases of perceived exerÂtion. Med Sci Sports Exer 1982;14:377-81.

https://doi.org/10.1249/00005768-198205000-00012

33. Carvajal A, Hribernik N, Duarte E, et al. The Spanish Version of the Edmonton Symptom Assessment System- Revised

(ESAS-r): First Psychometric Analysis Involving Patients with Advanced Cancer.

J Pain Symptom ManÂage 2013;45:129-36.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpainsymÂman.2012.01.014

34. Llamas-Ramos I, Llamas-Ramos

R, Buz J, et al. Construct Validity of the Spanish Versions of the Memorial

SympÂtom Assessment Scale Short Form and Condensed Form: Rasch Analysis of

Responses in Oncology Outpatients. J Pain Symptom Manage 2018;55:1480-91.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2018.02.017

35. Simon PM, Schwartzstein RM,

Weiss JW, Fencl V, TeghtÂsoonian M, Weinberger SE. Distinguishable Types of

Dyspnea in Patients with Shortness of Breath. Am Rev Respir Dis 1990;142:1009-14. https://doi.org/10.1164/ajrccm/142.5.1009

36. Wilcock A, Crosby V, Hughes

A, Fielding K, Corcoran R, Tattersfield AE. Descriptors of

breathlessness in patients with cancer and other cardiorespiratory diseases.

J Pain Symptom Manage. 2002;23:182-9.

https://doi.org/10.1016/S0885-3924(01)00417-1

37. Chowienczyk S, Javadzadeh S,

Booth S, Farquhar M. AsÂsociation of Descriptors of Breathlessness With Diagnosis and Self-Reported Severity of Breathlessness

in Patients With Advanced Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease or Cancer. J

Pain Symptom Manage 2016;52:259-64.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2016.01.014

38. Tanaka K, Akechi T, Okuyama

T, Nishiwaki Y, Uchitomi Y. Development and validation of the Cancer Dyspnoea

Scale: a multidimensional, brief, self-rating scale. Br J Cancer 2000;82:800-5. https://doi.org/10.1054/bjoc.1999.1002

39. Kimpara K, Shinichi A, Maki

T, Yuichi T. Working Memory Impacts Endurance for Dyspnea. Physiotherapists, Eur Respir J 2020;56:2455.

https://doi.org/10.1183/13993003.congress-2020.2455.

40. Williams MT, John D, Frith P.

Comparison of the DysÂpnoea-12 and Multidimensional Dyspnoea Profile in people

with COPD. Eur Respir J 2017;49:1600773.

https://doi.org/10.1183/13993003.00773-2016.

41. Koskela J, Kupiainen H, Kilpeläinen M, et al. Longitudinal HRQoL shows divergent trends and identifies constant deÂcliners

in asthma and COPD. Respir Med 2014;108:463-71.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rmed.2013.12.001

42. Meek PM, Banzett R, Parsall

MB, et al. Reliability and validity of the multidimensional dyspnea profile.

Chest 2012;141:1546-53.

https://doi.org/10.1378/chest.11-1087.

43. Belo LF, Rodrigues A,

Vicentin AP, et al. A breath of fresh air: Validity and reliability of a

Portuguese version of the Multidimensional Dyspnea Profile for patients with

COPD. PLoS One 2019;14:e0215544.

https://doi.org/10.1371/jourÂnal.pone.0215544.

44. Mahler DA, Wells CK.

Evaluation of Clinical Methods for Rating Dyspnea. Chest 1988;93:580-6.

https://doi.org/10.1378/chest.93.3.580

45. Guidance Respiratory

questionnaire and instructions to interviewers (1966)

https://www.ukri.org/publications/respiratory-questionnaire-and-instructions-to-interviewÂers-1966/.

46. Güell R, Casan P, Sangenís M, et al. Traducción

española y validación de un cuestionario de calidad de vida en

paciÂentes con enfermedad pulmonar obstructiva crónica. Arch Bronconeumol 1995;31:202-10.

https://doi.org/10.1016/S0300-2896(15)30925-X

47. Guyatt GH, Berman LB,

Townsend M. Long-term outcome after respiratory rehabilitation. CMAJ 1987;137:1089â95.

48. Guyatt GH, Berman LB,

Townsend M, Pugsley SO, ChamÂbers LW. A measure of quality of

life for clinical trials in chronic lung disease. Thorax 1987;42:773-8. https://doi.org/10.1136/thx.42.10.773.

49. Guyatt GH, Townsend M, Berman

LB, et al. A comparison of Likert and visual analogue scales for measuring

change in function. J Chronic Dis 1987;40:1129-33.

https://doi.org/10.1016/0021-9681(87)90080-4

50. Valero-Moreno S,

Castillo-Corullón S, Prado-Gascó VJ, Pérez-Marín M,

Montoya-Castilla I. Chronic Respiratory Disease Questionnaire (CRQ-SAS):

Analysis of psychoÂmetric properties. Arch Argent Pediatr 2019;117:149-56. https://doi.org/10.5546/aap.2019.eng.149.

51. Guyatt GH, Townsend M, Berman

LB, Pugsley SO. QualÂity of life in patients with chronic

airflow limitation. Br J Dis Chest. 1987;81:45-54. https://doi.org/10.1016/0007-0971(87)90107-0.

52. Cella DF, Bonomi AE, Lloyd

SR, et al. Reliability and validity of the functional assessment of cancer

therapy-lung (FACT-L) quality of life instrument. Lung Cancer 1995;12:199-220. https://doi.org/10.1016/0169-5002(95)00450-F121

53. Groenvold M, Petersen MA,

Aaronson NK, et al. The develÂopment of the EORTC QLQ-C15-PAL: A shortened quesÂtionnaire

for cancer patients in palliative care. Eur J Cancer 2006;42:55-64.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejca.2005.06.022

54. Groenvold M, Petersen MA,

Aaronson NK, et al. EORTC QLQ-C15-PAL: the new standard in the asÂsessment of

health-related quality of life in adÂvanced cancer? Palliat Med 2006;20:59-61.

https://doi.org/10.1191/0269216306pm1090ed

55. Pilz MJ, Aaronson NK, Arraras JI, et al. Evaluating the Thresholds for Clinical Importance of

the EORTC QLQ-C15-PAL in Patients Receiving Palliative Treatment. J Palliat Med 2021;24:397-404.

https://doi.org/10.1089/jpm.2020.0159.

56. Bergman B, Aaronson NK,

Ahmedzai S, et al. The EORTC QLQ-LC13: a modular supplement to the EORTC core

qualÂity of life questionnaire (QLQ-C30) for use in lung cancer clinical

trials. Eur J Cancer 1994;30:635-42.

https://doi.org/10.1016/0959-8049(94)90535-5

57. Nicklasson M, Bergman B.

Validity, reliability and clinical relevance of EORTC QLQ-C30 and LC13 in

patients with chest malignancies in a palliative setting. Qual Life Res 2007;16:1019-28. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-007-9210-8.

58. Bausewein C, Farquhar M,

Booth S, et al. Measurement of breathlessness in advanced disease: A systematic

review. Respir Med 2007;101:399-410.

59. Lovell N, Etkind SN, Bajwah

S, et al. To What Extent Do the NRS and CRQ Capture Change in Patientsâ

Experience of Breathlessness in Advanced Disease? Findings From a Mixed-Methods

Double-Blind Randomized Feasibility Trial. J Pain Symptom Manage 2019;58:369-81.e7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2019.06.004

60. Bourke SC, McColl E, Shaw PJ,

Gibson GJ. Validation of quality of life instruments in ALS. Amyotroph Lateral

Scler Other Motor Neuron Disord 2004;5:55-60.

https://doi.org/10.1080/14660820310016066.

61. Dorman S, Byrne A, Edwards A.

Which measurement scales should we use to measure breathlessness in palliative

care? A systematic review. Palliat Med 2007;21:177-91. https:// doi.org/10.1177/0269216307076398.

62. Booth S, Adams L. The shuttle

walking test: a reproducÂible method for evaluating the impact of shortness of

breath on functional capacity in patients with advanced cancer. Thorax 2001;56:146-50. https://doi.org/10.1136/thorax.56.2.146.

63. Wilcock A, Crosby V, Clarke

D, et al. Reading numbers aloud: a measure of the limiting effect of

breathlessness in patients with cancer. Thorax 1999;54:1099-103.

https://doi.org/10.1136/thx.54.12.1099

64. Wilcock A, Walker G,

Manderson C, et al. Use of Upper Limb Exercise to Assess Breathlessness in

Patients with Cancer: Tolerability, Repeatability, and Sensitivity. J Pain

Symptom Manage 2005;29:559-64.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2004.09.003

65. Mori M, Yamaguchi T, Matsuda Y, et al. Unanswered questions and future direction in the

management of terminal breathlessness in patients with cancer. ESMO Open 2020;5 Suppl 1: e000603.

https://doi.org/10.1136/esmoopen-2019-000603.

66. Koller M, Warncke S,

Hjermstad MJ, et al. European OrgaÂnization for Research and Treatment of

Cancer (EORTC) Quality of Life Group; EORTC Lung Cancer Group. Use of the lung

cancer-specific Quality of Life Questionnaire EORTC QLQ-LC13 in clinical

trials: A systematic review of the literature 20 years after its development.

Cancer 2015;15;121:4300-23.

https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.29682.

67. Campbell ML. Psychometric

testing of a respiratory distress observation scale. J Palliat Med 2008;11:44-50. https://doi.org/10.1089/jpm.2007.0090.

68. Campbell ML, Templin T, Walch

J. A Respiratory Distress Observation Scale for patients unable to self-report

dysÂpnea. J Palliat Med 2010;13:285-90.

https://doi.org/10.1089/jpm.2009.0229.

69. Zhuang Q, Yang GM, Neo SH-S,

et al. Validity, Reliability, and Diagnostic Accuracy of the Respiratory

Distress ObserÂvation Scale for Assessment of Dyspnea in Adult Palliative Care

Patients. J Pain Symptom Manage 2019;57:304-10.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2018.10.506

70. Chesteen K, Kothare N, Huth

H, Misra S. Implementing a Respiratory Distress Scale for Unconscious Patients

in a Palliative Care Unit. J Pain Symptom Manage 2022;63:871.

https://doi.org//10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2022.02.063.

71. Decavèle M, Rivals I,

Persichini R, et al. Prognostic Value of the Intensive Care Respiratory

Distress Observation Scale on ICU Admission. Respir Care 2022;67:823-32.

https://doi. org/10.4187/respcare.09601

72. Decavèle M, Rozenberg

E, Niérat M-C, et al. Respiratory distress observation scales to predict

weaning outcome. Crit Care 2022;26:162.

https://doi.org/10.1186/s13054-022- 04028-712