Autor : De Vito, Eduardo L.1-2

1 Medical Research Institute Alfredo Lanari, Faculty of Medicine, University of Buenos Aires, Buenos Aires, Argentina. 1Centro del Parque, Respiratory Care Department, Buenos Aires, Argentina.

https://doi.org/10.56538/ramr.OKRA7194

Correspondencia : Eduardo Luis De Vito, eldevito@gmail.com

ABSTRACT

All the theories about the

mechanisms of generation of dyspnea had defenders and detractors and,

interestingly, with the development of sophisticated neurophysiological techniques

and functional imaging, it has been possible to rank each one of them. All have

survived the passage of time and none can singularly explain dyspnea in all

cliniÂcal situations, showing the complex and multifactorial nature of the

phenomenon. The concept of length-tension inappropriateness has found support

in recent decades with new evidence in its favor. Specially

with the discovery of the pathways involved and with the application of

neurophysiological knowledge, the length-tension inappropriateÂness theory

would be refined with the corollary discharge or efferent copy. This corolÂlary

discharge or efferent copy is a basic attribute of the nervous system found in

the animal kingdom, from invertebrates to primates and in the human species.

This article is dedicated to the history of the efferent copy and its

incorporation as a hypothesis to explain dyspnea, which is currently the most

accepted one.

Key words: Dyspnea, Breathing Mechanics, Corollary Discharge, Efferent Copy

RESUMEN

Todas

las teorÃas sobre los mecanismos de generaciÃģn de disnea tuvieron defensores y

detractores e, interesantemente, con el desarrollo de sofisticadas tÃĐcnicas

neurofisiÂolÃģgicas y de imÃĄgenes funcionales ha sido posible jerarquizar cada

uno de ellos. Todas han sobrevivido al paso del tiempo y ninguna puede explicar

por sà sola la disnea en todas las situaciones clÃnicas, lo cual habla de la

naturaleza compleja y multifactorial del fenÃģmeno. El concepto de inadecuaciÃģn

tensiÃģn y longitud hallÃģ en las Últimas dÃĐcadas un sustento con nuevas

evidencias a su favor. En particular, con el hallazgo de las vÃas involucradas

y con la aplicaciÃģn de conocimientos neurofisiolÃģgicos, la teorÃa de la

inadecuaciÃģn tensiÃģn y longitud se verÃa refinada con la descarga corolaria o copia eferente. Esta descarga corolaria o copia eferente es un atributo bÃĄsico del

sistema nervioso, que se encuentra en el reino animal, desde los invertebrados

a los primates y en la especie humana. Este artÃculo estÃĄ dedicado a la

historia de la copia eferente y su incorporaciÃģn como hipÃģtesis para explicar

la disnea, la mÃĄs aceptada en la actualidad.

Palabras

clave: Disnea,

MecÃĄnica respiratoria, Descarga corolaria, Copia

eferente

Received: 11/26/2022

Accepted: 07/31/2023

INTRODUCTION

Why canât we tickle ourselves?

Why doesnât an electric fish electrocute itself? Why doesnât the strong

vibration of a cricketâs legs disturb it? Why donât bats confuse their sounds

with those of others? and ultimately, why do we

experience dyspnea? Because of the efferent copy (EC) or corollary discharge

(CD).1

An EC or CD is a fundamental

attribute of the nervous system found in the animal kingdom, from invertebrates

to primates, and in the human speÂcies.1

This article is dedicated to the history

of the EC and its incorporation as a hypothesis to explain dyspnea, which is

currently the most accepted one.

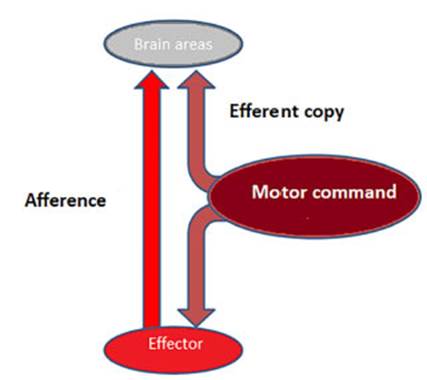

When the motor system sends a

signal to a muscle, it also sends an internal copy of the sigÂnal that does not

exit the central nervous system (CNS). This internal signal is called the

âefferent copyâ or âcorollary dischargeâ. This EC or CD is compared with the

sensory input or reafferent, which comes from the

moving muscle. If the EC/ CD and the reafferent are

equal, it means that the intended movement is the same as the executed

movement. This prevents unnecessary self-induced perceptions (Figure 1).

The command sent from a motor region

of the central nervous system (motor command) is copÂied and sent to other

regions of the CNS before the movement occurs. Subsequently, the effector

(e.g., muscle) sends afferent information to the CNS, where both signals are

compared. If both signals are equal (intended movement = executed movement),

there are no unnecessary self-induced perceptions.

HISTORY OF THE EFFERENT COPY

The first to propose the

existence of the EC was Hermann von Helmholtz in the mid-19th century: the

CNS needed to create an EC from the motor command that controls the eye muscles

in order to help the brain determine the location of an object in relation to

the head. He coined the term âpsychoÂphysicsâ and established a precise and

non-linear relationship between the magnitude of physical stimuli and the

perceived intensity. Helmholtz paved the way for the development of the psychoÂphysical

laws of Weber and Stevens.

The initial concept of EC was

disregarded for 75 years after Sir Charles Scott Sherrington (NoÂbel Prize in

Medicine in 1932) strongly criticized Hermann von Helmholtzâs ideas in 1920.2 It was not

until the mid-20th century that Erich von Holst and Horst Mittelstaedt,

in 1950, described the principle of reafference to

explain how an orÂganism is able to distinguish between a reafferent

(self-generated) sensory stimulus and an exafferÂent

(externally generated) stimulus.3 This concept

contributed to the understanding of interactive processes between the CNS and

its periphery and received a total of 2973 citations.

It was Roger Wolcott Sperry

(Nobel Prize in Physiology in 1981) who, thanks to his research on the optokinetic nystagmus reflex,

introduced the concept of the CD and is considered the creator of that term.4 His article

has been cited 1636 times. The EC has been implicated in the lack of dyspnea in

patients with COVID-19,5 a hypothesis that deserves to be explored in

greater detail.

Differences between efferent copy and corollary discharge

Through different experimental

lines, Von Holst and Mittelstaedt3 primarily

referred to the concept of âefferent copyâ while their contemporary SperÂry4 coined the

concept of âcorollary dischargeâ. The first concept involves a real copy of the

motor command (the efference) directed to the

muscles. This term seemed appropriate for the questions that Von Holtz and Mittelstaedt addressed in inÂvertebrates and for the

general analysis of sensory processing that takes place in relation to motor

discharge. However, it has become evident that the connection between motor and

sensory areas can be produced at several levels of motor control.

Through studies on fish, Sperry4 used the

second concept, âcorollary dischargeâ to denote motor sigÂnals that influence

sensory processing. However, his conception was less specific as regards the

location where the motor discharge to the sensory pathways should arise. So,

the terms have a differÂent history and some differences regarding the level of

complexity, but they are often used interchangeÂably. For the purposes of

this article, they will be mentioned interchangeably.

In the coming decades, the

concept of âefferÂent copyâ will expand significantly. Poulet

et al suggested the use of CD as a broad concept to encompass neural signals

generated in motor cenÂters that are not directly used to generate ongoing

motor activity but often act to modulate sensory processing.6

TAXONOMIC CLASSIFICATION OF EFFERENT COPIES OR COROLLARY DISCHARGE

How is sensory

processing connected in inverteÂbrates and dyspnea in humans? What taxonomic

type of internal copy produces dyspnea? Crapse and Sommer suggested a functional taxonomic classifiÂcation of

efferent copies for the entire animal kingÂdom.1

Corollary discharge can be globally classified into categories of

lower and higher order based on the function and operational impact of the

signal.

The lower-order signaling

is ubiquitous, as it is necessary for any animal equipped with sensory and

motor systems. In this context, corÂollary discharge is a discriminatory mechanism

that prevents maladaptive responses and sensory overload by restricting or

filtering information. The cricket doesnât stun itself (and it can hear other

environmental noises), and the electric fish doesnât electrocute itself.

When Titi

monkeys howl, they face the same problem as crickets: initially, the sounds

they emit should affect their hearing. A protective mechaÂnism can be observed

in the primary auditory cortex of the Titi monkey,

where many neurons are suppressed during self-vocalization. SuppresÂsion begins

about 200 ms before vocalization and continues

throughout its duration. This could be a case where the CD interconnects motor

and sensory areas that occupy comparable spaces of a sensorimotor pathway.1

Higher-order signaling plays a role in two types of functions. On the perceptual side,

it facilitates the contextual interpretation of sensory information (analysis)

and the construction and maintenance of an internal representation of this

information (stability). On the sensorimotor side, it facilitates the

acquisition of new motor patterns (learning) and the execution of sequences of

rapid movements (planning). This type of corolÂlary discharge allows specific

brain structures to make appropriate adjustments in anticipation of the sensory

input. Each bat only hears its own sound and not the sound of others, enabling

them to build a cohesive representation of the world. So far, the

higher-order CD has only been identified in vertebrates.

There isnât a single type of CD,

but rather numerous subtypes that correspond to both the anatomical levels of

the source and the target, as well as functional utilities.1

As can be observed, this taxonomy illustrates the crucial point

that, although Sperryâs original concept4

of CD aligns with the general flow of information from motor

systems to sensory systems throughout the animal kingdom, it appears

inappropriately simplistic to use a single concept to describe the signal.

IDENTIFICATION OF COROLLARY DISCHARGE PATHWAYS

The neurons mediating these

signals have been hard to identify. The first evidence came from a single multisegmental interneuron of CD responÂsible for

presynaptic and postsynaptic inhibition of auditory neurons in cricket singing

(Gryllus biÂmaculatus).6 Similar structures were found in the tadpole, the river

crab, and the sea slug Aplysia. Studies in

these species contribute to the classiÂcal understanding of CD: they project

and target regions involved in the processing of reafferent

information.

However, sensory processing is highly

dynamic, taking into account the behavioral state of the animal. Therefore,

analyzing sensory pathways in preparations under anesthesia or at rest may not

provide a complete picture of sensory processing. Perhaps, in evolutionary

terms, the CD initially modulated real activity, and then, in more complex

brains, also targeted the regions involved in sensoÂrimotor integration or

motor planning.7

Our muscles are sensitive; this

includes the respiratory muscles. In other words, we receive sensory signals

from muscles that reach our consciousness and inform us about what is hapÂpening

in those muscles, similar to how sensory signals from the skin tell us what is

happening there. Studies in animals showed that a copy of the respiratory

motor impulse is transmitted to the midbrain and thalamus.1-8

DYSPNEA AND COROLLARY DISCHARGE

In 1978, with an article that got

more than 1000 citations, McClosky et al suggested

that corollary discharge signals, or ECs

originating from the respiratory centers in the brainstem can be transÂmitted

to higher brain centers and give rise to a conscious awareness of the output

motor command. This may play a significant role in the formation of the

sensation of dyspnea.11

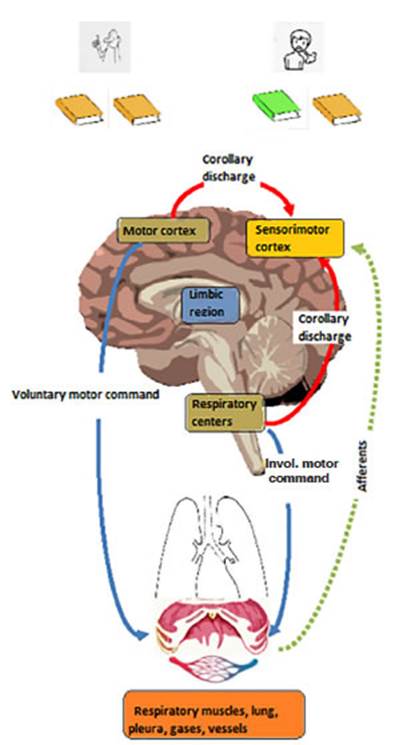

The concept of CD is the most

widely accepted to explain the origin of the sensation of inspiratory effort

and dyspnea.12-14 The proposed scheme for the respiratory system is

essentially the same as the one described in Figure 1. Unlike pain recepÂtors,

the afferents projecting to the higher brain centers to compare with the EC are

diverse.15 Additionally, the respiratory system has an autoÂmatic

(brainstem) and voluntary (motor cortex) motor command. This CD from different

sources most likely gives rise to different sensations.15

Therefore, in our opinion, dyspnea is not merely a carbon copy of

pain.

Figure 2 depicts the CD in the

respiratory system, with its dual involuntary and voluntary innervation. During

involuntary breathing, respiÂratory centers send an EC to the sensory cortex,

whereas during voluntary respiratory efforts, it is the motor cortex that sends

the copy. SimultaneÂously, the respiratory muscles send afferents to the

sensory cortex. When there is proper corresponÂdence between the motor command

and incoming afferent information from sensory receptors, there shouldnât be

any sensation of dyspnea (Figure 2). On the contrary, when there is no

correspondence, the resulting neuromechanical

uncoupling conÂtributes to the genesis of dyspnea. This exchange between the

motor command and the sensory cortex is currently the most accepted mechanism

by which awareness of respiratory effort is achieved.

If both copies (efferent and reafferent) are equivalent (same color), there is no

dyspnea; if the copies differ (different color), dyspnea occurs.

Why is our breathing not usually self-perceived?

The sensory cortex also receives

afferents from events that occur in the chest and respiratory muscles and

processes the information.14 When it receives the EC, the sensory cortex adjusts acÂcordingly

to minimize, eliminate, or compensate for the sensory consequences of movement.

Due to this general strategy, breathing under normal conditions is an

unconscious process1 (and within

certain ventilation limits).

What is the relationship between the length-tension inappropriateness of

Campbell and the efferent copy?

In fact, a dissociation between

the motor command and the mechanical response of the respiratory system recalls

the theory of length-tension inapÂpropriateness by Campbell and Howell in the

1960s.15 The theory

has been generalized to include not only information arising in the respiratory

muscles but also the one emanating from receptors throughout the entire

respiratory system, and has been named with various terms.15-19

â Neuromechanical

dissociation.

â Efferent-reafferent

dissociation.

â Length-tension

inappropriateness.

â Neuroventilatory

dissociation.

â Afferent discordance

(mismatch).

â Neuromechanical

decoupling.

â Neuromuscular dissociation.

What respiratory conditions can have a dissociation

between efferent and afferent information and result in dyspnea?

In addition to the mentioned

neurophysiological findings, various experimental data and clinical

observations are consistent with the concept of efferent-afferent

inappropriateness.20-25

In both patients and healthy

individuals, temporary suppression of ventilation during speech or eating causes

a mismatch between the respiratory motor command and the expected movement.

When normal subjects breathe CO2, their

ventilation increases, and most experience dysÂpnea. However, if ventilation is

reduced while CO2 remains constant,

subjects report a marked increase in the intensity of breathlessness, even

though the chemical drive to breathe has not changed.

When normal subjects are forced

to breathe at an inspiratory flow that is different from what they have chosen

as the most comfortable, they experience a sensation of air hunger.

A similar phenomenon can occur in

patients receiving mechanical ventilation and showing unsuitability for the

respirator.

All of this suggests that, under

a given set of conditions, the brain âexpectsâ a certain ventilaÂtion pattern

and associated afferent feedback, and deviations from this pattern cause or

intensify the sensation of dyspnea.

Is there any relationship between corollary discharge and the lack of

dyspnea in patients with COVID-19?

COVID-19 is surprising and

intriguing in various aspects. One of its relevant characterÂistics is the

ability to recognize the absence of dyspnea in the majority of cases. If the physiopathological mechanisms of dyspnea developÂment are

not yet well understood, we shouldnât be surprised, since we have limited

knowledge of the dyspnea mechanisms in COVID-19.5

In some series, intubated and ventilated subjects exhibited

tachypnea and tachycardia.26-28 In a

retrospective study, dyspnea and chest tightness were much more common in

deceased patients.29 Dyspnea was

one of the associated predictors of severe illness and death.30

To understand the absence of dyspnea in COVID-19, the main focus

is on phenotypes that show severe hypoxia and almost normal respiratory system distensibility. In respiratory distress due to COVID-19

pneuÂmonia, the respiratory system (transpulmonary distensibility and driving pressure) was reported to be

pseudonormal.31,

32 From

a physiopathoÂlogical perspective, which does not

exclude the direct neurotoxic effect of the virus and a systemic response in

the infectious context but rather encompasses it, the lack of dyspnea in

COVID-19 can be explained by an adaptation in the sensory cortex of the brain

of the two signals coming from the motor command and the periphery via CD.5

CONCLUSIONS AND THERAPEUTIC PROJECTIONS

All animals, from the humble

nematode to the cognitively advanced primate require the type of signaling that

allows the CD which protects against unnecessary self-induced perceptions. We

are still in an embryonic stage of CD research in the animal kingdom. However, the

exchange between the motor command and the sensory corÂtex is currently the

most accepted mechanism by which awareness of respiratory effort is achieved. Neuronal

pathways have been identified. Indeed, a dissociation

between the motor command and the mechanical response of the respiratory sysÂtem

recalls the Campbell and Howellâs âlength-tension inappropriatenessâ theory

from the 1960s. The future goal will be to discover how the CD influences

perception. Experiments so far have shown that inactivation of CD pathways can

alter behavior, and subtle perceptual changes may justify these behavioral

alterations. This knowledge may be highly relevant for the relief of refractory

dyspnea.

KEY POINTS

âĒ Clinical,

experimental, neurophysiological data, and clinical observations support the concept of a lack of tension-length adequacy, neuroÂmechanical dissociation, or efferent-reafferent dissociation (EC/CD) as the central core in the

genesis of dyspnea.

âĒ The central concept is that,

under a given set of conditions, the brain âexpectsâ a certain ventilaÂtion

pattern and associated afferent feedback; deviations from this pattern cause or

intensify the sensation of dyspnea.

âĒ It is necessary to go deeper

into the role of CD in the absence of dyspnea in COVID-19 as well as in other

conditions.

REFERENCES

1. Crapse

TB, Sommer MA. Corollary discharge

across the animal kingdom. Nat Rev Neurosci

2008;9:587-600. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrn2457

2. Efference

copy [Internet]. Available from:

https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Efference_copy&oldid=841428446).

3. Von Holst E, Mittelstaedt H. Das Reafferenzprinzip:

Wechselwirkungen zwischen Zentralnervensystem und Peripherie.

Sci Nat 1950;37:464-76.

https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00622503

4. Sperry RW. Neural

basis of the spontaneous optokinetic response

produced by visual inversion.J Comp Physiol Psychol 1950;43:482-9. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0055479

5.

De Vito EL. Possible Role of Corollary Discharge in Lack of

Dyspnea in Patients With COVID-19 Disease [Internet].

Front Physiol 2021;12.

http://dx.doi.org/10.3389/fphys.2021.719166

6. Poulet

JF, Hedwig B. The cellular basis of a corollary disÂcharge.

Science. 2006;311: 518-22.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1126/science.1120847.

7. Poulet

JF, Hedwig B. New insights into corollary discharges mediated by identified

neural pathways. Trends Neurosci 2007;30:14-21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tins.2006.11.005

8. Chen Z, Eldridge FL, Wagner

PG. Respiratory-associated rhythmic firing of midbrain neurones

in cats: relation to level of respiratory drive [Internet]. The Journal of

Physiology 1991;437:305-25.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1113/jphysiol.1991.sp018597

9. Chen Z, Eldridge FL, Wagner

PG. Respiratory-associated thalamic activity is related to level of respiratory

drive [Internet]. Respiration Physiology 1992; 90:99-113.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0034-5687(92)90137-l

10. Matthews PBC. Where Does

Sherringtonâs âMuscular Senseâ Originate? Muscles, Joints, Corollary

Discharges? [Internet]. Annual

Review of Neuroscience 1982; 5: 189-218.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1146/annurev.ne.05.030182.001201

11. McCloskey DI. Kinesthetic sensibility. Physiol

Rev 1978;58:763-820.

https://doi.org/10.1152/physrev.1978.58.4.763

12. Spengler CM, Banzett RB, Systrom DM, Shannon

DC, Shea SA. Respiratory sensations during heavy exercise in

subjects without respiratory chemosensitivity.

Respir Physiol 1998;114:65-74. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0034-5687(98)00073-5

13. Booth S, Dudgeon D. Dyspnoea in Advanced Disease: A Guide to Clinical

Management. Oxford University Press; 2006. 271 p.

https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780198530039.001.0001

14. Fukushi

I, Pokorski M, Okada Y. Mechanisms underlying the

sensation of dyspnea. Respir Investig

2021;59:66-80.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resinv.2020.10.007

15. Campbell EJ, Howell JB. The sensation of breathlessness. Br Med Bull 1963;19:36-40.

https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordjournals.bmb.a070002

16. Parshall

MB, Schwartzstein RM, Adams L, et al. An OfÂficial

American Thoracic Society Statement: Update on the Mechanisms, Assessment, and

Management of Dyspnea. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2012;185:435-52.

https://doi.org/10.1164/rccm.201111-2042ST

17. OâDonnell DE, Webb KA. Exertional

breathlessness in patients with chronic airflow limitation. The role of lung hyperinflation. Am Rev Respir

Dis 1993;148:1351-7.

https://doi.org/10.1164/ajrccm/148.5.1351

18. Banzett

RB, Lansing RW, Brown R, Topulos GP, Yager D, Steele SM, et al. âAir hungerâ from increased PCO2 persists

after complete neuromuscular block in humans. Respir Physiol 1990;81:1-17.

https://doi.org/10.1016/0034-5687(90)90065-7

19. Nishino T. Dyspnoea: underlying mechanisms and treatment. Br J Anaesth 2011;106: 463-74.

https://doi.org/10.1093/bja/aer040

20. Manning HL, Molinary EJ, Leiter JC. Effect of inspiratory flow rate on respiratory sensation and

pattern of breathing. Am J Respir

Crit Care Med 1995; 151: 751-7.

https://doi.org/10.1164/ajrccm/151.3_Pt_1.751

21. Manning HL, Schwartzstein RM. Pathophysiology of DysÂpnea [Internet]. N

Engl J Med 1995;333:1547-53.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1056/nejm199512073332307

22. Chonan

T, Mulholland MB, Cherniack NS, Altose

MD. EfÂfects of voluntary constraining of thoracic

displacement during hypercapnia. J Appl Physiol 1987;63:1822-8. https://doi.org/10.1152/jappl.1987.63.5.1822

23. Schwartzstein

RM, Simon PM, Weiss JW, Fencl V, WeinÂberger SE.

Breathlessness induced by dissociation beÂtween ventilation and chemical drive.

Am Rev Respir Dis 1989;139:1231-7.

https://doi.org/10.1164/ajrccm/139.5.1231

24. Manning HL, Shea SA, Schwartzstein RM, Lansing RW, Brown R, Banzett

RB. Reduced tidal volume increases âair hungerâ at fixed PCO2 in ventilated quadriplegics. Respir Physiol 1992;90:19-30. https://doi.org/10.1016/0034-5687(92)90131-F

25. Schwartzstein

RM, Manning HL, Woodrow Weiss J, WeinÂberger SE. Dyspnea: A sensory experience

[Internet]. Lung 1990; 168: 185-99. Available from:

http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/bf02719692

26.

Al-Omari A, Alhuqbani WN, Zaidi ARZ, et al. Clinical charÂacteristics

of non-intensive care unit COVID-19 patients in Saudi Arabia: A descriptive

cross-sectional study. J Infect Public Health 2020; 13: 1639-44.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jiph.2020.09.003

27.

Guan WJ, Ni ZY, Hu Y, et

al. Clinical Characteristics of Coronavirus Disease 2019

in China. N Engl J Med 2020;382:1708-20.

https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa2002032

28. Li YC, Bai

WZ, Hashikawa T. The neuroinvasive

potential of SARS-CoV2 may play a role in the respiratory failure of COVID-19

patients. J Med Virol 2020;92:552-5.

https://doi.org/10.1002/jmv.25728

29. Chen T, Wu D, Chen H, et al.

Clinical characteristics of 113 deceased patients with coronavirus disease

2019: retrospective study. BMJ 2020;368:m1091.

https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.m1091

30. Kaeuffer

C, Le Hyaric C, Fabacher T,

et al. Clinical charÂacteristics and risk factors associated with severe COÂVID-19:

prospective analysis of 1,045 hospitalised cases in

North-Eastern France, March 2020. Euro Surveill

[Internet] 2020;25(48).

http://dx.doi.org/10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2020.25.48.2000895

31. Bhatraju PK, Ghassemieh BJ,

Nichols M, et al. Covid-19 in Critically Ill Patients in the Seattle Region -

Case Series. N Engl

J Med. 2020;382:2012-22.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa2004500.

32. Viola L, Russo E, Benni M, et al. Lung mechanics in type L CoVID-19

pneumonia: a pseudo-normal ARDS. Transl Med Commun 2020;5:27.

https://doi.org/10.1186/s41231-020-00076-9