Autor : Rojas Mendiola, Ramiro Horacio1, Smurra, Marcela Viviana1

1 Center for Respiratory Failure and Sleep Laboratory, Pulmonology Division, Hospital General de Agudos Enrique TornĂș, Buenos Aires, Argentina

https://doi.org./10.56538/ramr.XREG8277

Correspondencia :Ramiro H. Rojas Mendiola, email: rhrojasmd@gmail.com

ABSTRACT

Introduction: Treatment with positive airway pressure is one of the cornerstones in

managing obstructive sleep apnea (OSA). However, access to the equipment and adÂherence

to their use are not easy to achieve. Objective: to evaluate the adherence of

patients from the public health system who receive continuous pressure devices

free of charge for the treatment of OSA.

Materials and methods: Patients diagnosed with OSA who received continuous posiÂtive airway

pressure (CPAP) devices between 2013 and 2018 through PAMI (Programa

de AtenciĂłn MĂ©dica

Integral, Medical Services Program) , Incluir Salud, and Cobertura Porteña de Salud were retrospectively evaluated.

Results: Patients from PAMI were older and had a lower score in the Epworth

scale. The delay between the consultation and the diagnosis was 1.4 ± 2.4

months. The time from the diagnosis until the equipment was provided was 10.2 ±

9.9 months. Patients from PAMI received the equipment faster (2.7 ± 2.5 months)

and were more adherent to follow-up visits. Adherence

to clinical follow-up visits in the first year was 46 %. Older patients with a

lower Epworth score and those using AutoCPAP had a

non-significant trend favoring this adherence. The objective adherence measured

by memory card or telemonitoring was 40 %. The higher

body mass index (BMI) was the only factor favorÂing objective adherence.

Conclusions: Overcoming the economic limitation to access the equipment does not

change the attitude towards adherence and follow-up.

Key words: Sleep Apnea; Obstructive, Continuous Positive Airway Pressure, Patient

Compliance

RESUMEN

IntroducciĂłn:

El

tratamiento con presiĂłn positiva es uno de los pilares del manejo de las apneas

obstructivas del sueño, sin embargo, el acceso a los equipos y la adherencia a

su uso no son fĂĄciles de lograr.

Objetivo:

Evaluar

la adherencia de los pacientes del sistema pĂșblico de salud que reÂciben

equipos de presiĂłn continua de forma gratuita para el

tratamiento de las apneas obstructivas del sueño.

Material

y métodos: Se

evaluĂł retrospectivamente a los pacientes con diagnĂłstico de apnea obstructiva

del sueño que recibieron equipos de CPAP entre 2013 y 2018 a través de PAMI,

Incluir Salud y Cobertura Porteña de Salud.

Resultados:

Los

pacientes de PAMI fueron de mayor edad y tenĂan un Epworth

mås bajo. La demora entre consulta y diagnóstico fue de 1,4 ± 2,4 meses. El

tiempo de diagnóstico a provisión del equipo fue de 10,2 ± 9,9 meses. Los

pacientes de PAMI recibieron los equipos mås råpido (2,7 ± 2,5 meses) y fueron

mĂĄs adherentes a las visitas de control. La adherencia a los controles clĂnicos

el primer año fue del 46 %. Los pacientes de mayor edad, con Epworth mĂĄs bajo y que usan auto-CPAP tenĂan una tendencia

no significativa a favorecer esta adherencia. La adherencia objetiva medida por

tarjeta de memoria o telemonitoreo fue del 40 %. El

mayor IMC fue el Ășnico factor que la favorecĂa.

Conclusiones:

Superando

la limitaciĂłn econĂłmica al acceso a los equipos, no cambia la actitud hacia la

adherencia y control.

Palabras

clave: Apneas

del sueño; PresiĂłn positiva continua en la vĂa aĂ©rea; Adherencia

Received :11/08/2022

Accepte:11/24/2023

INTRODUCTION

Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) is

defined by the presence of recurrent episodes of apneas or hyÂpopneas secondary

to pharyngeal collapse during sleep, leading to desaturations and

micro-arousals. When these events are associated with a set of signs and

symptoms, they constitute the obstrucÂtive sleep apnea-hypopnea syndrome

(OSAHS). The traditionally accepted prevalence of OSAHS in the general

population is 3.1 to 7.5 % in men and 1.2 to 4.5 % in pre-menopausal women.

However, recent epidemiological studies describe an even higher prevalence. 1

Taking into account the population

data in Argentina, in 2010, there were 40,117,096 inhabÂitants, 91 % of whom lived in urban areas, with a male/female ratio of

0.95/1. Approximately 65 % of the population is concentrated in the Central

region, especially in the province of Buenos Aires, which accounts for 38.9 %

of the countryâs populaÂtion, particularly in the Autonomous City of BueÂnos

Aires (CABA) and its surroundings.

The Argentinian Healthcare System

is made up of national and provincial ministries, as well as a network of

public hospitals and health centers that provide free care to anyone in need,

particularly those in the lowest income quintiles, without social security or

without the capacity to pay for health services. In the city of Buenos Aires,

the population that has public health coverage, without resources or through

the Cobertura Porteña

de Salud (CPS, Buenos Aires Health Coverage)

provided by the Government of CABA, represented 18.7 % during the year 2017.

The population with social health insurance (Obra

Social) was 46.1 %, prepaid health care plan, 28 %, and coverage from other

systems 7.2 %.3 Additionally,

the National Institute of SoÂcial Services for Retirees and Pensioners

(INSSJP), through the Medical Services Program (PAMI), provides coverage to

retirees of the national welÂfare system and their families, reaching 20 % of

the population, with an expenditure that accounts for 0.75 % of the GDP.4

Individuals with pension benefits

or disability pension receive coverage from the National GovÂernment (formerly

PRO.FE, currently Incluir Salud) and also seek diagnosis and follow-up care at

hospitals in CABA.

At the Hospital Enrique TornĂș, an average of 235,500 patients consulted the

Diagnostic Services per year, from 2013 to 2018. The Sleep and ReÂspiratory

Failure Laboratory receives 600 annual consultations from patients without

coverage, members of PAMI, and those with social health insurance coverage.

Our objective is to describe the

hospitalâs situÂation regarding patients with state coverage that addresses

economic limitations, a key aspect of access to treatment.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This is a descriptive

retrospective study of patients with coverage from PAMI, Incluir

Salud, and CPS who were diagnosed with OSAHS

between 2013 and 2018 and were able to access treatment with continuous airway

pressure (CAP) devices, either CPAP, Auto CPAP, or BiPAP

(bilevel positive airway pressure). Patients who

purchased their own devices and those with social health insurance were

excluded.

Data were obtained from the

medical records of patients older than 18 years who first consulted during this

period and were diagnosed with OSA either through polygraphy

or polysomnography, and initiated treatment with PAP

devices. As it is a referral center, some patients come to the consultation

with the study already performed. Data were collected on sex, age, Body Mass

Index (BMI), neck circumference (NC), and daytime sleepiness using the Epworth

Sleepiness Scale (ESS).

Polygraphy studies were conducted using two different devices. The first is a Resmed Apnea LinkÂź

device that records airflow signals through a nasal pressure

cannuÂla, snoring derived from a nasal cannula, oximetry,

and pulse frequency. The signal analysis is performed using ApneaLink

software version 8 with automatic analysis and subsequent manual review. The

second device is an Embla Embletta

GoldÂź model that records airflow signals through a nasal pressure

cannula, snoring derived from a nasal canÂnula, thoracic and abdominal movement

using XactTraceÂź RIP (Respiratory

Inductance Plethysmography) belts, pulse oximetry, and body position. The signals are evaluated

using RemLogic-E software version 1.3 with automatic

analysis and manual review of events. For polysomnography

studies, an ATI Praxis18 AMP18P - Lermed S.R.L.

device is used. In each study, three EEG (electroencephalogram) channels were

recorded: 3, C4, and O1 with references on the mastoids (A1 and A2), two EOG (electrooculogram) channels (right and left), three EMG

(electromyogram) channels, ECG (electrocardiogram), airflow measurement through

thermistor and nasal pressure cannula, piezoelecÂtric thoracic and abdominal

bands for effort, body position sensor, pulse oximetry,

and a microphone. The records are manually analyzed using DelphosDB

software version 1.75.32.4 (Lermed S.R.L.) according

to the standards of the American Association of Sleep Medicine (AASM).7

The calibration procedure is

performed with polysomnoÂgraphic control or during 3

nights at home in order to reduce equipment ordering times. The devices used

for calibration are: REMstar auto with Aflex (Philips-Respironics) and

S9 (Resmed). Once the calibrations are completed, an

effective treatment pressure is established by the deviceâs software, as

effective pressure (P) during 90 or 95 % of the approÂpriate device usage time,

with system leaks of less than 24 liters/minute. Finally, the type of device is

noted, whether it has fixed pressure (CPAP), automatic variable pressure (AutoCPAP), or bilevel pressure (BiPAP).

The next step is the equipment

request. For patients without coverage, a form is completed that evaluates the

clinical and social situation to qualify for a request as Medical aid. Under

this designation, a request number is generated, categorized as âHospital

Supplyâ in the FinanÂcial Management and Administration Integrated System of

the Ministry of Health of the Government of CABA, where the resource provided

by the Ministry is directly available. Based on the availability of funds, a

bidding process is initiated with the submission of proposals from equipment

suppliers. Technical support is provided by the sleep laboÂratory doctors

according to each patientâs requirements. Upon confirmation of the final

amount, the equipment purchase is made, and the device is delivered to the patient

from 2 months on. In cases of urgent equipment provision, the administrative

resource of Emergency Purchase can be used, resulting in equipment acquisition

within one month. This administrative model has been in operation since 2016.

Between 2013 and 2016, a similar procedure was followed, but there were some

variations in supply times due to administrative issues beyond our control.

For PAMI patients, a specific

supply form is completed; it must then be renewed every 6 months. The bidding

process of the equipment is carried out for each patient, in every INSSJP

agency, depending on the patientâs address.

After the equipment is delivered,

a sleep laboratory doctor explains the basic care aspects of the equipment, he/she tests the mask, and checks the proper

functioning of the equipment. Follow-up visits are scheduled according to

national guidelines, one month after the beginning of treatment, at 3 months,

and then every 6 months. A contact phone number is provided for difficulties

that could arise between scheduled consultations.

The mean times that were

evaluated include: from consultation to diagnosis, from previous studies until

conÂsultation, from equipment request until provision, from equipment provision

until the first follow-up visit, and follow-up in the last 12 months. Adherence

to treatment was also evaluated basing on the presence or absence of a

follow-up visit one year after equipment delivery, the subjective use of

devices without memory, the objective use of devices with compliance memory

card, and the use in patients undergoing telemedicine.

Differences were analyzed between

adherents and non-adherents to follow-up visits, regardless of their equipment

provision method. In the subgroup of patients monitored with memory card or

telemedicine, differences were sought between those with more than 70 %

adherence and those without.

Patients who do not attend

scheduled follow-up visits during the last year are contacted to assess the use

of their equipment.

Statistical analysis

The data were collected in Excel

spreadsheets and processed using the EPI Info 7 program. The data are described

with measures of central tendency and dispersion according to the type of variable.

Differences between categorical variables were compared using the chi-square

test,2 and

continuous variables were analyzed using the Studentâs t-test. A p-value of

less than 0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

The data of 148 patients were

evaluated. A first group of 84 patients received the equipment from the

Government of the City of Buenos Aires and the National Government, referred to

as the Hospital Group (HG); and a second group of 64 patients with health

coverage received the equipment through the Social Services System for Retirees

and Pensioners and were called the PAMI group.

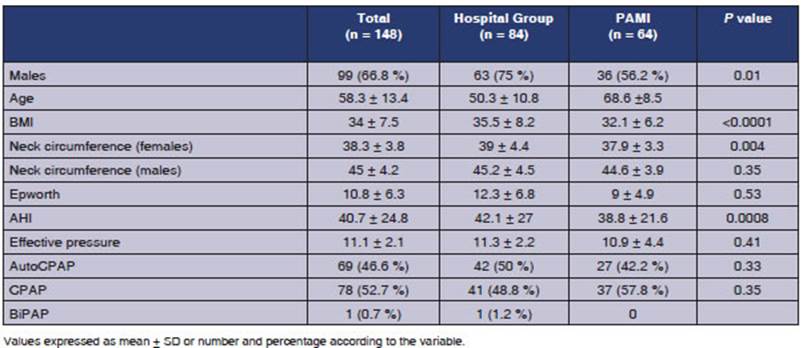

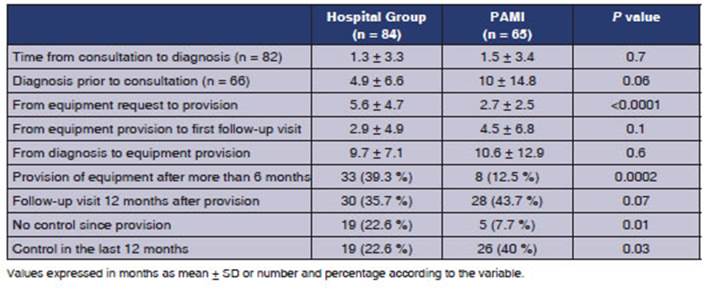

The characteristics of the

patients are presented in Table 1. The waiting times for diagnosis,

treatÂment, and follow-up are presented in Table 2.

Values expressed in months as

mean ± SD or number and percentage according to the variable

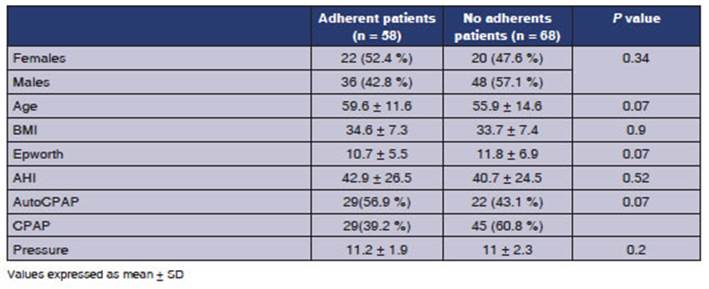

In a sub-analysis, patients who

had not yet completed 1 year of treatment by the statistical cutoff date were

excluded. Those who attended follow-up visits during the first year were

grouped as adherents. This group was compared with the remaining patients in order

to identify factors favoring adherence. Results are presented in Table 3.

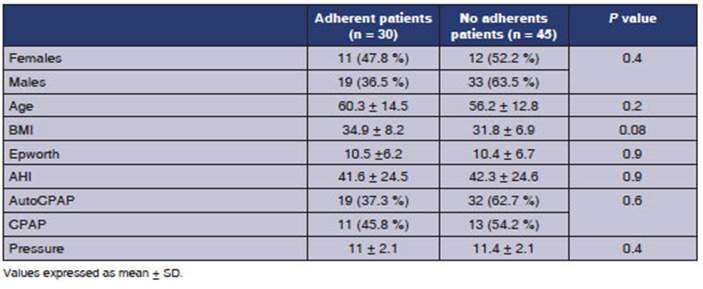

The objective adherence in

patients who had memory cards or were monitored through the cloud, defined as more

than 70 % of use for more than 4 nights per week, was only 40 %, with no

statistically significant differences between adherÂent and non-adherent

patients in the analyzed variables. Table 4.

91 patients who hadnât attended

any follow-up visit in the last year were contacted: 51.6 % reÂported that they

were still using the CPAP; 6.6 % had returned the device due to intolerance;

3.3 % had the device but werenât using it; and 38.5 % of patients couldnât be

located.

DISCUSSION

Our study found that

patients from the Hospital Group (HG) are younger but have a higher BMI and

higher levels of daytime sleepiness according to the Epworth Sleepiness Scale.

The age differÂences between groups are due to the fact that patients from the

PAMI group are mostly retired individuals, while the HG group consists of

middle-aged patients. Lee et al observed that the BMI does not correlate with

the apnea/hypopnea index (AHI) in patients older than 70 years.11 AdditionÂally, the Sleep Health Heart Study showed that

correlation and also demonstrated that sleepiness is less prevalent in elderly

patients compared to middle-aged individuals.12

In our study, the

delays in the access to the diagÂnostic study were 1.4 months. Access to

diagnostic procedures is deficient worldwide. A review on this topic in 2004

found significant variability among the analyzed countries, with Belgium having

the shortest waiting time, with average delays ranging from 2 weeks to 2

months. In the United States, significant differences are observed between cenÂters

and hospitals, with average waiting times ranging from 2 weeks to 9 months. In

other counÂtries, such as the United Kingdom, the average is 4 months; in Australia,

5 months, and in Canada, 24 months. It is important to note that there are

differences within each country, with Ontario, for example, having a waiting

time of only 2 months.13

The use of continuous airway

pressure devices is considered the standard treatment for patients with

moderate to severe OSAHS. UnderstandÂing the obstacles and difficulties in

accepting and adhering to CPAP is crucial for an effective treatment and the

development of an adherence protocol.

Access to the

equipment is the first barrier to treatment. A recent study in six Latin

American countries showed that 28.7 % of the patients who could not initiate

CPAP treatment lacked economic resources to purchase the equipment.14

In Mexico, Torre B. et al observed that 45 % of patients with a CPAP

prescription failed to acquire the equipÂment, considering the economic aspect

an essential causal factor.15 Through economic incentives for

patients with low socioeconomic status, CPAP acceptance rates of 70 % were

achieved.16 The Argentinian public healthcare system enables all

patients diagnosed with OSAHS to access the equipment. However, in our study,

treatment adherence during the first year was only 39 %, similar to the

findings by Tarasiuk et al (35 to 39 %).16 Another study in Belgium demonstrated that CPAP acceptance

was higher when there was economic reimbursement from social security, but

found no differences with regard to adherence and compliance after more than 2

years of follow-up.17

There are few studies

about delays in treatment initiation. A cohort study in Ontario with 216,514

patients who started CPAP treatment between 2006 and 2013 showed a mean delay

of 138 +/- 202 to 196 +/- 238 days since the diagnosis in hospital sleep

laboratories versus 119 +/- 167 to 150 +/- 202 days in community sleep

laboratories, with 33.6 % of patients taking more than 6 months to receive the

equipment.18 Our study has a much smaller sample size, but we

obtained provision times of 130.4 +/- 130.9 days, with shorter times in the

PAMI system and only 12.2 % of patients taking more than 6 months to receive

the equipment.

In a systematic

literature review from 1994 to 2015 about CPAP adherence, an average usage rate

of 36.3 % was observed with a mean use of 4.6 hours per night that did not

improve over time.19 Baratta et al found

that adherence to the use of CPAP for more than 4 hours per night and more than

5 days per week was 41.4 %, with an average follow-up of 74.8 months.20

This value is similar to what was found in our group of patients with objective

CPAP adherence. In contrast, a study conducted in Denmark with 695 patients who

received a free AutoCPAP under a strict follow-up

protocol achieved compliance rates of 77.7 %, with an average follow-up of 3

years, showing higher adherence in severe patients. Furthermore, they found

that the severity of the OSAHS, daytime sleepiness, and smoking are independent

factors for treatment adherence.21 Kohler et al evaluated long-term

follow-up at the Oxford Centre for Respiratory Medicine, and found 81 % adherence

at 5 years, and 70 % at 10 years, with an mean use of 6.2 hours per night, with

the desaturation index being the only factor favoring long-term adherence in

the multivariate analysis.22 In the study by Santin

et al, it was observed that 60.5 % of patients continued using CPAP at an

average of 12.3 months of follow-up, with age, Epworth Scale score, and AHI

being the factors favoring long-term adherence.23 Torre B. et al

reported an 80 % adherence to CPAP at 34 months post-prescription, which was related

to a higher respiratory distress index (RDI).15 Our study found that

age, the EpÂworth Scale score, and the use of AutoCPAP

over the CPAP had a non-significant trend in favor of adherence to follow-ups,

while the increased BMI was the only factor showing a non-significant trend

toward improving objective adherence. These findÂings lack statistical

significance, probably due to the smaller number of patients.

There should be an

initial consultation with a specialist before the start of treatment, followed

by frequent visits to a specialist nurse in the field of sleep disorders for

adjustments in the CPAP combination, the mask type, and the use of huÂmidification

(if deemed necessary), until patient tolerance is achieved. Subsequently, there

should be follow-up visits at least once a year.21

The decision of

patients to sleep in another room has been shown to be a predictor CPAP

treatment acceptance.24 This suggests that

eduÂcating the patientâs partner and family environment is important to maintain

good adherence. In a systematic review by Cochrane, low-quality evidence was

found regarding individual support interventions (frequent consultations, phone

calls, telemedicine, home visits, and group meetÂings for patients) and

behavioral therapy (face-to-face or online motivational interviews) to improve

the use of CPAP; and there is moderate-quality evidence for in-person or

distance educational interventions.25

CPAP equipment

providers can play a crucial role in the treatment of sleep apnea by helping

patients to select the most suitable devices and masks and providing training

on proper usage. In a study conducted in Germany, the equipment provider

company evaluated the use of a patient support tool. This tool provided

personalized eduÂcation on the use of the mask,

the humidifier and overall device usage. Additionally, the company offered

usage tips and encouraging messages, all tailored to

the device usage data. These intervenÂtions resulted in improvements in the

number of hours of use, reduced leakage, and lower rates of treatment

withdrawal.26

CONCLUSIONS

With the data obtained in our

analysis, we found significant delays in accessing the diagnosis of OSA and

treatment with CPAP. These delays are longer in patients without medical coverage

compared to those with PAMI coverage. Adherence to CPAP use is still low even

after overcoming economic limitations in the access to treatment equipment.

Age, the baseline Epworth score, and the use of auto-adjustable deÂvices would

favor treatment adherence. More interventions from various healthcare system

stakeholders are needed to achieve optimal use of CPAP equipment and obtain all

the benefits of treatment.

Conflict of interest

Authors have no conflict of

interest to declare in relation to the topic of this manuscript. This work

was carried out without funding.

REFERENCES

1. Nogueira FB, Cambursano H, Smurra M, et al. GuĂas prĂĄcticas de diagnĂłstico y

tratamiento del sĂndrome de apneas e hipopneas

obstructivas del sueño: Actualización 2019. Rev Am Med Resp. 2019;19:31.

2. Jonas DE, Amick HR, Feltner C, et al.

Screening for Obstructive Sleep Apnea in Adults: Evidence Report and Systematic

Review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. JAMA.

2017;317:415-33. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2016.19635

3. Peppard PE, Young T, Barnet JH, et al. Increased prevalence

of sleep-disordered breathing in adults. Am J EpideÂmiol. 2013;177:1006-14.

https://doi.org/10.1093/aje/kws342

4. Redline S, Sotres-Ălvarez D, Loredo J, et

al. Sleep-disordered breathing in Hispanic/Latino individuals of diverse

backgrounds. The Hispanic Community Health Study/ Study of

Latinos. Am J Respir Crit Care Med, 2014:189:335- 644.

https://doi.org/10.1164/rccm.201309-1735OC

5. Simpson L, Hillman

DR, Cooper MN, et al. High prevalence of undiagnosed obstructive sleep apnoea in the general population and methods for screening

for repreÂsentative controls. Sleep Breath. 2013;17:967-73.

https:// doi.org/10.1007/s11325-012-0785-0

6. Arnardottir ES, Bjornsdottir E, Olafsdottir KA, et al. Obstructive sleep apnoea in the general population: highly prevalent but

minimal symptoms. Eur Respir

J. 2016;47:194-202.

https://doi.org/10.1183/13993003.01148- 2015

7. Shahar E, Redline S, Young T, et al. Hormone replacement

therapy and sleep-disordered breathing. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2003;167:1186-92.

https://doi.org/10.1164/rccm.200210-1238OC

8. Argentina, INdEyCR. Censo 2010. 2010;

Available from:

https://www.indec.gob.ar/nivel4_default.asp?id_

tema_1=2&id_tema_2=41&id_tema_3=135.

9. Arce HE. OrganizaciĂłn y financiamiento del sistema de salud en

la Argentina [The Argentine

Health System: organization and financial features]. Medicina (B Aires). 2012;72:414-8.

10. (Argentina), MdS. El acceso a la

salud en Argentina: III encuesta de utilizaciĂłn y gasto en servicios de salud

2010. 2010; Available from:

http://www.msal.gob.ar/fesp/images/stories/recursos-de-comunicacion/publicaciones/estudio_carga_enfermedad.pdf.

11. Lee YG, Lee YJ, Jeong DU. Differential Effects of Obesity on Obstructive

Sleep Apnea Syndrome according to Age. Psychiatry Investig. 2017;14:656-61.

https://doi.org/10.4306/pi.2017.14.5.656

12. Young T, Shahar E, Nieto FJ, et al. Predictors of sleep-disordered

breathing in community-dwelling adults: the Sleep Heart Health Study. Arch

Intern Med. 2002;162:893- 900.

https://doi.org/10.1001/archinte.162.8.893

13. Flemons WW, Douglas NJ, Kuna ST, et al. Access to diagnoÂsis

and treatment of patients with suspected sleep apnea. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2004;169:668-72.

https://doi.org/10.1164/rccm.200308-1124PP

14. Nogueira JF, Poyares D, Simonelli G, et al., Accessibility and adherence to

positive airway pressure treatment in patients with obstructive sleep apnea: a

multicenter study in Latin America. Sleep Breath. 2020;24:455-64.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s11325-019-01881-9

15. Torre Bouscoulet L, LĂłpez EscĂĄrcega

E, Castorena MalÂdonado A, VĂĄzquez GarcĂa JC, Meza Vargas MS, PĂ©rez- Padilla R.

Uso de CPAP en adultos con sĂndrome de apneas obstructivas durante el sueño

despuĂ©s de prescripciĂłn en un hospital pĂșblico de referencia de la Ciudad de

MĂ©xico [Continuous positive airway

pressure used by adults with

obstructive sleep apneas after prescription in a public referral hospital in Mexico City]. Arch Bronconeumol. 2007;43:16-21. https://doi.org/10.1157/13096996

16. Torre Bouscoulet L, LĂłpez EscĂĄrcega

E, Castorena MalÂdonado A, VĂĄzquez GarcĂa JC, Meza Vargas MS, PĂ©rez- Padilla R.

Uso de CPAP en adultos con sĂndrome de apneas obstructivas durante el sueño

despuĂ©s de prescripciĂłn en un hospital pĂșblico de referencia de la Ciudad de

MĂ©xico [Continuous positive airway

pressure used by adults with

obstructive sleep apneas after prescription in a public referral hospital in Mexico City]. Arch Bronconeumol. 2007;43:16-21.

https://doi.org/10.1157/13096996

17. Leemans J, Rodenstein D, Bousata J, Mwenge GB. Impact of

purchasing the CPAP device on acceptance and long-term adherence: a Belgian

model. Acta Clin Belg. 2018;73:34-9. https://doi.org/10.1080/17843286.2017.1336294

18. Rotenberg B, George

C, Sullivan K, Wong E. Wait times for sleep apnea care

in Ontario: a multidisciplinary assessment. Can Respir

J. 2010;17:170-4. https://doi.org/10.1155/2010/420275

19. Rotenberg BW, Murariu D, Pang KP. Trends in CPAP adÂherence over twenty

years of data collection: a flattened curve. J Otolaryngol

Head Neck Surg. 2016;45:43.

https://doi.org/10.1186/s40463-016-0156-0

20. Baratta F, Pastori D, Bucci T, Fabiani M, Fabiani V, Brunori M, et al.

Long-term prediction of adherence to continuous positive air pressure therapy

for the treatment of moderate/severe obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. Sleep

Med. 2018;43:66-70.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sleep.2017.09.032

21. Jacobsen AR, Eriksen F, Hansen RW, et al. Determinants for adherence to

continuous positive airway pressure therapy in obstructive sleep apnea. PLoS One.

2017;12:e0189614.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0189614

22. Kohler M, Smith

D, Tippett V, Stradling JR.

Predictors of long-term compliance with continuous positive airway pressure. Thorax. 2010;65:829-32.

https://doi.org/10.1136/thx.2010.135848

23. SantĂn M J, Jorquera A J, JordĂĄn J,

et al. Uso de CPAP nasal en el largo plazo en sĂndrome de apnea-hipopnea del sueño [Long-term continuous positive airway presÂsure (CPAP) use in obstructive

sleep apnea]. Rev Med Chil. 2007;135:855-61.

https://doi.org/10.4067/S0034-98872007000700005

24. Kiely JL, McNicholas WT. Bed partnersâassessment of nasal continuous positive airway

pressure therapy in obstructive sleep apnea. Chest.

1997;111:1261-5. https://doi.org/10.1378/chest.111.5.1261

25. Wozniak DR, Lasserson TJ, Smith I. Educational, supportive and behavioural interventions to improve usage of continuous

positive airway pressure machines in adults with obstructive sleep apnoea. Cochrane Database Syst

Rev. 2014:CD007736. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD007736.pub2

26. Woehrle

H, Arzt M, Graml A, et al.

Effect of a patient engagement tool on positive airway pressure adherÂence:

analysis of a German healthcare provider dataÂbase. Sleep Med. 2018;41:20-6.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sleep.2017.07.026