Autor : Cafaro, Mario A.1, Benavidez Rodrigo A.2, Yaryura Montero José G.3, Navarro Ricardo4

1Staff Surgeon of the Thoracic Surgery Service. Sanatorio Allende, CĂłrdoba city, capital of the Province of CĂłrdoba, Argentina. 2Chief of the Thoracic Surgery Service. Sanatorio Allende, CĂłrdoba city, capital of the Province of CĂłrdoba, Argentina. 32nd year Resident of the Thoracic Surgery Service. Sanatorio Allende, CĂłrdoba city, capital of the Province of CĂłrdoba, Argentina. 4Consultant Surgeon of the Thoracic Surgery Service. Sanatorio Allende, CĂłrdoba city, capital of the Province of CĂłrdoba, Argentina.

https://doi.org/10.56538/ramr.YZBD4253

Correspondencia :Mario Cafaro E-mail: mariocafaro.t@gmail.com

ABSTRACT

Introduction: The disease caused by SARS-CoV-2 has become a significant public health

issue. 5 % of the patients required endotracheal intubation due to acute hypoxÂemic

respiratory failure, leading to an increased number of consultations for

tracheal stenosis. This work was done with the aim of presenting the results of

tracheal resection in patients with post-COVID-19 stenosis.

Material and methods: Analytical, prospective, observational study. 11 patients were included.

The preoperative and postoperative evaluation was the same for all patients.

Post-surgical ventilation and phonation were assessed up to 30 days. The Clavien and Dindo classification

was used to grade post-surgical complications, with follow-up extended up to 60

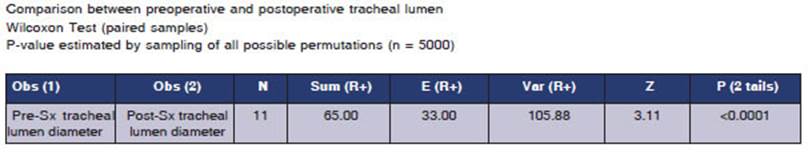

post-surgical days. Statistical analysis: the Wilcoxon test was used to compare

the results.

Results: 27.2 % of the patients had postoperative complications. The comparison

of pre- and postoperative ventilation (p < 0.05) was statistically

significant, with improveÂment in the postoperative period. When comparing pre-

and postoperative fiberoptic bronchoscopy (tracheal

lumen diameter), the result was also statistically significant (p < 0.05).

Conclusion: The results obtained are similar to those expressed in the literature.

TraÂcheal resection is a safe and effective procedure and should be considered

as first-line treatment for tracheal stenosis.

Key words: Coronavirus, Tracheal stenosis, Intubation, Intratracheal,

Thoracic surgery

RESUMEN

IntroducciĂłn:

La

enfermedad por SARS-CoV-2 se convirtiĂł en un importante problema de salud

pĂșblica. El 5 % de los pacientes requiriĂł intubaciĂłn endotraqueal

por insuficienÂcia respiratoria aguda hipoxĂ©mica, y

se generĂł un aumento de consulta por estenosis traqueal. Se realizĂł el trabajo

con el objetivo de expresar los resultados de la cirugĂa de resecciĂłn traqueal

en pacientes con estenosis post COVID 19.

Material

y métodos: Estudio

prospectivo, observacional, analĂtico. Se incluyeron 11 pacientes. La

evaluaciĂłn prequirĂșrgica y postquirĂșrgica fue la

misma en todos los pacientes. Se valorĂł en el postquirĂșrgico la ventilaciĂłn y

la fonaciĂłn hasta los 30 dĂas. Se utilizĂł la clasificaciĂłn de Clavien y Dindo para calificar a

las complicaciones posÂtquirĂșrgicas, con seguimiento hasta los 60 dĂas

postquirĂșrgicos. AnĂĄlisis estadĂstico: se aplicĂł prueba de Wilcoxon

para comparar los resultados.

Resultados:

El

27.2 % de los pacientes tuvieron complicaciones postquirĂșrgicas. Fue

estadĂsticamente significativa la comparaciĂłn de la ventilaciĂłn entre el prequirĂșrgico y el postquirĂșrgico (p<0.05) con mejorĂa

en el postquirĂșrgico. Al comparar la fibrobronÂcoscopĂa

prequirĂșrgica con la postquirĂșrgica (diĂĄmetro de la

luz traqueal) tambiĂ©n el resultado fue estadĂsticamente significativo (p

<0.05).

ConclusiĂłn:

Los

resultados obtenidos son similares a los expresados en la literatura. La

cirugĂa de resecciĂłn traqueal es un procedimiento seguro y efectivo y debe ser

considerada como tratamiento de primera lĂnea para la estenosis traqueal.

Palabras

claves: Coronavirus,

Estenosis Traqueal, IntubaciĂłn, Intratraqueal,

CirugĂa TorĂĄcica

Received: 07/07/2023

Accepted: 12/02/2023

INTRODUCTION

The disease caused by SARS-CoV-2

(COVID-19) spread rapidly worldwide and has become a sigÂnificant public health

issue. The first case was reported in 2019. This led to an unprecedented

increase in the number of patients requiring proÂlonged stays in the Intensive

Care Unit (ICU) due to respiratory complications caused by COVID-19. 5 % of

these patients required endotracheal inÂtubation and mechanical ventilation for

acute hypoxemic respiratory failure.1, 2

While orotracheal

intubation (OTI) is an esÂsential tool for the management of patients in the

intensive care unit, one of the complications it can generate is tracheal

stenosis. Although the incidence is low at present, thanks to applied new

technologies, it still exists. These advances began to be used after research

conducted by Grillo and Cooper in 1966,3 where they

determined the physiopathology of tracheal stenosis. The rate of laryngotracheal stenosis postintubation

(LSPI) in non-COVID-19 patients is between 10 and 22 %.4, 5 Although the rate of LSPI related to COVID-19

is still unknown, it is believed that this complicaÂtion is even more common.6 This could

possibly be due to the debate regarding the timing of the tracheostomy that

took place at the beginning of the pandemic (due to the risk of virus aerosolizaÂtion), leading to many cases being performed

late.7

We present the experience in

managing a series of consecutive patients who underwent surgical treatment.

OBJECTIVES

Primary

To assess the results

of the surgery in relation to ventilation and phonation.

Secondary

1. To determine surgery-related

morbidity and mortality according to the Clavien Dindo scale.

2. To compare our results with

those of the series of patients (with and without COVID-19) menÂtioned in the

literature.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

An analytical, prospective,

observational study was conÂducted. A database was created, including the

patients who underwent tracheal resection with primary anastomosis at the Sanatorio Allende, New CĂłrdoba and Cerro branches (CĂłrdoba

city, capital of the Province of CĂłrdoba, Argentina) between August 2021 and

September 2022.

All patients signed an informed

consent prior to surgery.

The study was reviewed and

approved by the Ethics Committee of the Sanatorio

Allende.

Inclusion criteria

âą Patients of both sexes, aged 16

and older, diagnosed with complex central airway stenosis following prolonged

intubation with mechanical respiratory support as a treatment for COVID-19.

Exclusion criteria

âą Patients with tracheal stenosis

greater than 5 centimeÂters and/or with general contraindications for surgical

treatment.

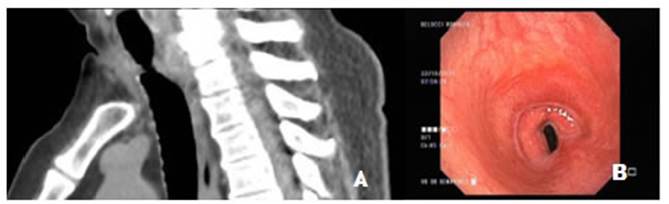

All the patients had a standard evaluation.

They unÂderwent axial, coronal and sagittal computed tomography scans (CT) and

flexible fiberoptic bronchoscopy (FFB). With the CT

and FFB results, both the length and location of the stenosis were determined.

A complex tracheal stenosis is considered

to be one exceÂeding 1 cm in length and with involvement of the tracheal wall.

Cases were classified according to the Myer-Cotton classification.8

In patients where the stenosis

affected the cricoid cartiÂlage, laryngotracheal

resection was considered.

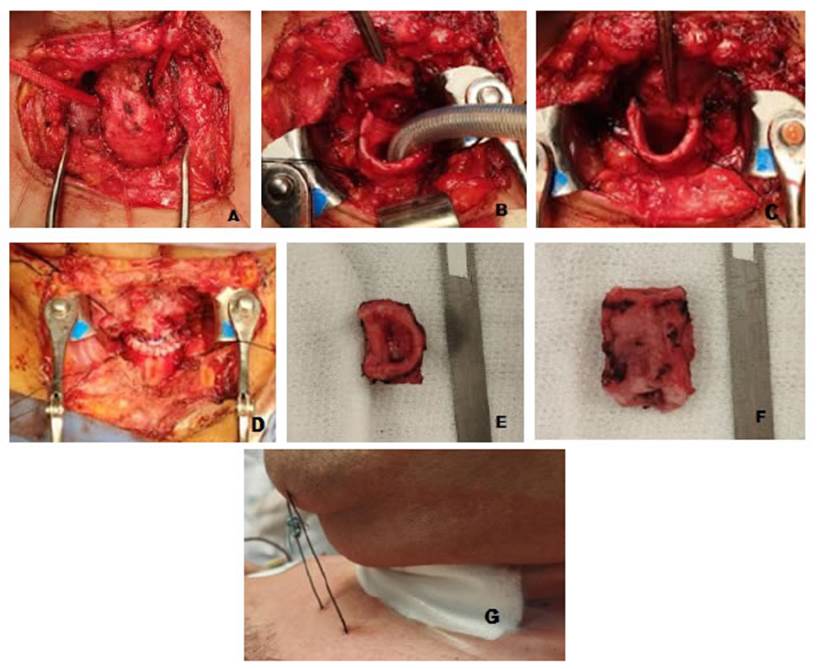

The surgical technique is similar

to that described by Mathisen9 with a few

modifications.

To the patient with tracheoesophageal fistula, closure of the opening on the

anterior face of the esophagus was perÂformed using 3.0 silk sutures on the mucosa

and muscular layers separately. Regarding anesthesia, all patients receiÂved

either inhalation gas or total intravenous anesthesia. In patients with severe

tracheal stenosis, tracheal dilation was performed prior to the placement of

the orotracheal tube. At the end of the surgery, the

patients were extubated.

To assess ventilation and

phonation, patients were evaÂluated at 7 days, 15 days, and 30 days

post-surgery.

Ventilation was assessed basing

on the presence or abÂsence of stridor in the postoperative period.

Phonation was assessed basing on

the presence or absÂence of dysphonia in the postoperative period.

The Clavien

and Dindo classification was used to grade

postoperative complications, with follow-up extended up to 60 days.

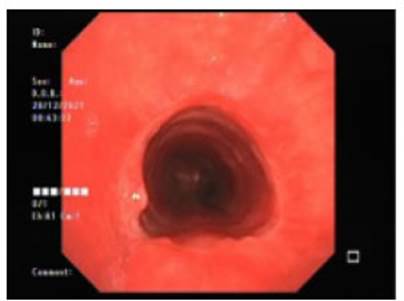

A new FFB was conducted on all

patients after 30 days to evaluate the status of the anastomosis.

Statistical analysis

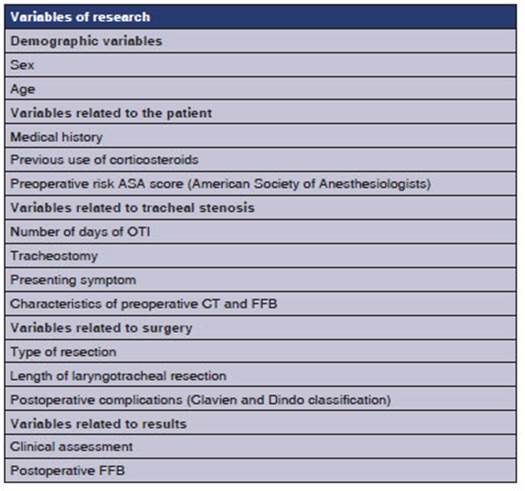

All the variables in research

were expressed in percentages, maximum, minimum, and median.

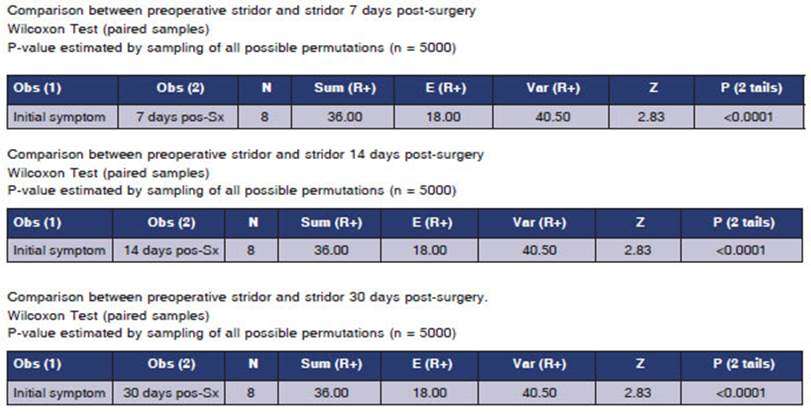

The Wilcoxon test was used to

compare the presence or absence of stridor on days 7, 14, and 30 after surgery

in patients who presented stridor as initial symptom, consiÂdering a p-value

< 0.05 as statistically significant.

The Wilcoxon test was also

applied to compare preoperaÂtive and postoperative fiberoptic

bronchoscopy, taking into account whether the postoperative fiberoptic

bronchoscopy showed a preserved tracheal lumen diameter or not; the

statistically significant value was p < 0.05.

RESULTS

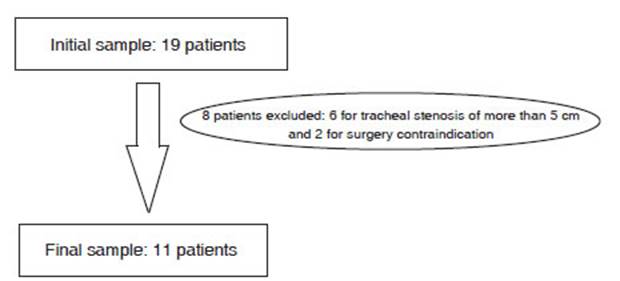

Out of the 19 initially evaluated

patients, 8 were excluded, resulting in a final sample size of 11 participants.

(Figure 1)

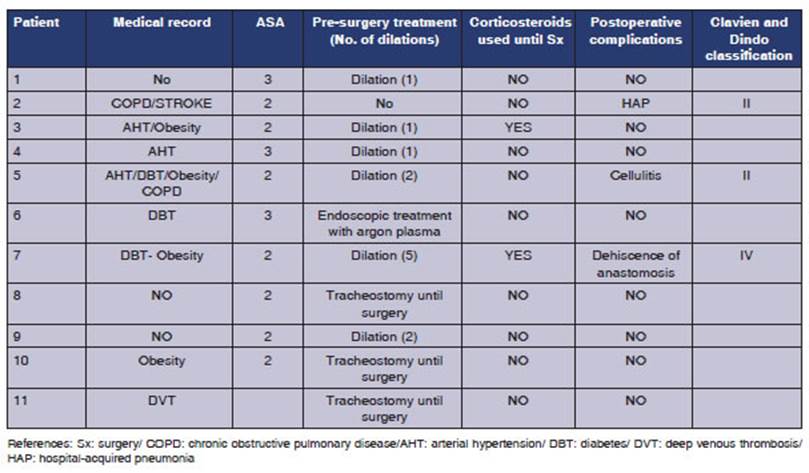

Of the included patients, 9 (81.8

%) were male, with a mean age of 52 years (MAX: 72 MIN: 32 MEDIAN: 47). Table 2

shows the medical record, surgical risk (ASA score), pre-surgery treatment,

history of corticosteroid use, and postoperative complications (Clavien Dindo classification).

27.2 % of the patients had postoperative complications.

Only one patient was

diagnosed with COVID-19 in the year 2020; the rest were diagnosed in 2021.

All the patients had

OTI, with an average of 13 days (MAX: 21 MIN: 8 MEDIAN: 12). 5 patients (45.4

%) underwent a tracheostomy. The average of days between the OTI and the

tracheostomy was 13 (MAX: 20 MIN: 9); and 3 patients (27.2 %) remained with the

tracheostomy until surgery; 2 of them due to total laryngotracheal

occlusion and the rest due to tracheoesophageal

fistula.

The presenting

symptoms and reasons for consultation were as follows: stridor and dyspnea

(36.3 %), stridor only (27.2 %), aphasia (18.1 %), stridor, dyspnea, and

dysphonia (9 %), and bronÂchoaspiration (9 %). The

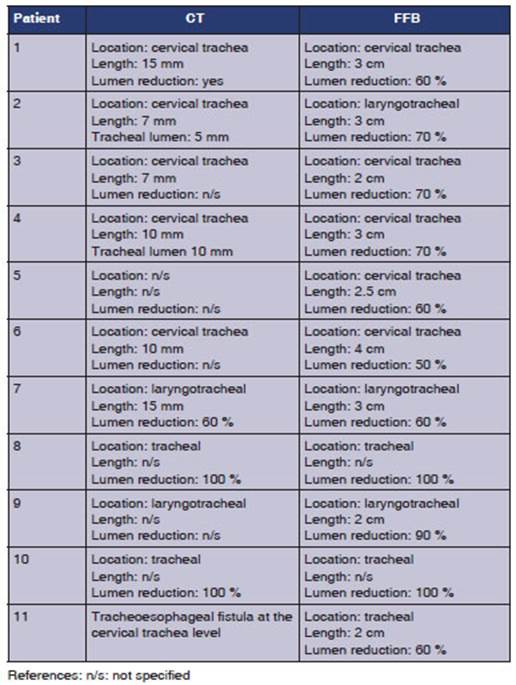

results observed in the neck CT and FFB are detailed in Table 3.

References: n/s: not

specified

According to the

Myer-Cotton classification, 8 patients were grade 2; 2 patients were grade 4,

and 1 patient was grade 3.

The average number of

months between the diagnosis of COVID-19 and tracheal resection surgery was 7

(MAX: 25 MIN: 2).

54.4 % of the

patients required at least one tracheal dilation prior

to surgery. One of the patients underwent endoscopic treatment using argon

plasma without the expected results before surgery.

Laryngotracheal resection was performed on 36.3 % of the patients,

and tracheal resection on 63.6 %.

The average duration

of surgery, measured in minutes, was 191 (MAX: 240 MIN: 120). The averÂage

hospital stay was 6 days (MAX: 7 MIN: 5). Onlyone patient required surgical reintervention

due to dehiscence of the anastomotic suture 47 days after surgery.

The average resection length

(measured in cm) was 2.9 (MIN: 1.5 MAX: 5).

There was no mortality at 60

days.

In the assessments at 7 and 14

days post-surÂgery, 5 patients showed dysphonia.

At the 30-day assessment, 4

patients experiÂenced dysphonia.

In the postoperative period,

endoscopic treatÂment with argon plasma was performed in only 1 patient for

granulomas at the anastomotic level.

Statistical analysis

Regarding the assessment of preoperative

stridor compared to the control at 7 days, no patients showed stridor; and the

same was observed at 14 days. Only one patient exhibited stridor at 30 days. In

this comparison, 8 patients were included, as 3 patients maintained the tracheÂostomy

until surgery, making the symptom unassessable.

The result of the comparison

between preoperaÂtive stridor and the assessment of the presence of this

symptom at 7, 14, and 30 days was statistically significant in all cases (p

< 0.05) (Table 4).

In the comparison between the

initial FFB and that of 30 days post-surgery, only one patient exÂhibited a

decrease in the diameter of the tracheal lumen. The result was statistically

significant (p > 0.05) (Table 5).

DISCUSSION

The approach to treat benign

tracheal stenosis is very complex, so it should be carried out in highly

experienced centers. It requires a trained team to do a proper evaluation and

determine the best treatment option, with tracheal resection and priÂmary anastomosis

being one of the choices.

There are very few studies in the

literature that show the results of tracheal surgery for benign stenosis, and

if we specifically focus on tracheal or laryngotracheal

resection for stenosis secondary to intubation from COVID-19, we find only two

studies, with the rest being case reports.

Regarding our results, the most

prevalent sympÂtom in the postoperative period was dysphonia, but it was mild

in all the cases, and it didnât prevent the patients from carrying out their

daily activities normally. Only one patient required endoscopic treatment

related to dysphonia, specifically due to granulomas on the vocal cords.

27.7 % of the

patients showed postoperative complications, with two being classified as mild

(Clavien Dindo II) and one

more severe: dehiscence of the anastomotic suture (Clavien

Dindo IV), which required emergency tracheostomy and

was a late complication, occurring 47 days post-surgery. This case was the

patient whose FFB showed a deÂcrease in the tracheal lumen 30 days

post-surgery. Upon analyzing the complications, it is observed that all three

patients were classified as ASA 3, and the patient with the most severe

complication continued using corticosteroids until the surgery and had

undergone 5 previous dilations. These are known risk factors for tracheal

resection surgery.10

The most common

presenting symptom was stridor, which was taken into account when assessÂing

ventilation in the postoperative period. When comparing the preoperative period

with control at days 7, 14, and 30 after surgery, the difference in the absence

of stridor was always statistically significant (p < 0.05), indicating the

positive outÂcomes of the surgery. The same trend was observed when comparing

the preoperative FFB with the one performed 30 days after surgery. The result

was also statistically significant (p < 0.05) for the preserved tracheal

lumen diameter in the postoperative period, which correlates with the absence

of stridor and underscores the success of the surgical treatment.

Piazzaâs work11 is the

only one in the literature showing the results of a case series involving

tracheal or laryngotracheal resection secondary to

tracheal stenosis caused by COVID-19. The number of patients treated in that

study is 14, very similar to our experience. The mean

age of the patients and the male-to-female ratio are also similar. In their

study, the mean duration of the OTI was 15.2 days, and a tracheostomy was

performed on 10 patients. In our work, the mean duration of the OTI was 13 days,

and a tracheosÂtomy was performed on 5 patients. Just like in our work, 3

patients arrived to the surgery with a tracheostomy.

With regard to the

location, in both studies, the most frequent location was the cervical trachea.

The most commonly performed procedure on patients before surgery was tracheal

dilation. In Piazzaâs work,11 the mean time

of hospitalization was 12.1 days, compared to 6 days in our study. They

documented a case of restenosis, whereas we had none in our study.

Another study that

shows results of tracheal surgery in patients with stenosis secondary to

prolonged intubation is the one from Palacios12. However, it

includes various tracheal procedures (tracheal resection, Montgomery T-tube

placeÂment, endoscopic treatment), and in the descripÂtion of the results, it

does not specify the technique that was used. The most frequently affected site

was the cervical trachea. According to the Myer- Cotton grading system, the

majority of the cases were grade III; in our work, the majority

were grade II.

The remaining

articles are related to tracheal surgery for tracheal stenosis but not

specifically associated with COVID-19.

Wrightâs work,10 evaluates the results of 392 patients

operated on at the Massachusetts General Hospital from 1993 to 2017. The mean

number of tracheal resections performed per year is 16.3; this figure aligns

with the significant number of patients included in our study. The study states

that the most common presenting symptoms are stridor, dyspnea, cough, and

dysphonia, very simiÂlar to those observed in our patients. In Wrightâs study,

92 % of patients received some form of treatment before surgery, compared to

63.6 % in our patient series. The mean length of tracheal resection was very

similar, with 3 cm in Wrightâs work and 2.9 cm in ours. The best outcomes were

obtained in patients without prior treatment for tracheal stenosis and without

prior use of corticoÂsteroids. That is why it is very important not to delay

the diagnosis.13

The overall morbidity

rate was 33 % in Wrightâs study versus 27.7 % in our work. There was dehisÂcence

of anastomosis in 4 % of Wrightâs patients compared to 9 % (1 patient) in our

series. Similar to our findings, in Wrightâs study there were no significant

differences between pure tracheal reÂsection and laryngotracheal

resection.

The study by Natuta14

reveals the results of 43 patients who underwent tracheal resection between

2007 and 2018, with a mean follow-up of 58 months. Similar to our findings, the

study did not report any deaths within the first 30 days. Dyspnea was measured

using the visual analogue scale for dyspnea, showing a noticeable improveÂment

in the postoperative period with statistically significant results. Regarding

voice assessment, it was determined that 30 patients experienced mild

deterioration.

The results presented

in the series of patients who underwent tracheal or laryngotracheal

resecÂtion for benign stenosis unrelated to COVID are

similar to those obtained in our study. This sugÂgests that this condition

should not significantly alter the treatment approach.

As for the

limitations of the study, it should be noted that the number of cases does not

allow for statistical analysis to relate variables studied in our work and

compare them with the results of non-COVID-19 patients.

CONCLUSION

The COVID-19 pandemic

posed a significant chalÂlenge for healthcare professionals worldwide. There

was a substantial increase in patient admissions to critical care units with the

need for OTI. Initially, due to concerns about virus aerosolization,

changes in guidelines were implemented, leading to delays in performing

tracheostomies. These factors conÂtributed to an increased rate of tracheal

stenosis.

For complex tracheal

stenosis, it is crucial to have a team with experience in tracheal surgery.

With appropriate indications, tracheal resection with primary anastomosis

should be considered the first option. In the hands of experienced surgeons, it

is a safe and effective procedure.

The postoperative

results in this series of paÂtients are similar to those with benign tracheal

stenosis unrelated to COVID-19.

A multicenter study

should be conducted to increase the number of cases and obtain more significant

results.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared

no conflict of interest

REFERENCES

1.

Guan WJ, Ni ZY, Hu Y, et

al. Clinical

characteristics of coronavirus disease 2019 in China. N Engl J Med 2020;382:1708-20.

https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa2002032

2. Wu Z, McGoogan

JM. Characteristics of and important lessons from the coronavirus disease 2019

(COVID-19) outbreak in China: summary of a report of 72314 cases from the

Chinese Center for Disease Control and PrevenÂtion. JAMA 2020;323:1239-42.

https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2020.2648

3. Cooper J.D, Grillo H.C. The evolution of tracheal inÂjury due to ventilatory assistance through cuffed tubes: a pathologic

study. Ann Surg 1969;169:334-48.

https://doi.org/10.1097/00000658-196903000-00007

4. Cooper J. Tracheal Injuries

Complicating Prolonged IntubaÂtion and Tracheostomy. Thorac

Surg Clin 2018;28:139-44. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.thorsurg.2018.01.001

5. Nouraei

SA, Ma E, Patel A, et al. Estimating the population incidence of adult

post-intubation laryngotracheal stenosis. Clin Otolaryngol 2007;5:411-2. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1749-4486.2007.01484.x

6. Alturk

A, Bara A, Darwish B. Post-intubation tracheal

stenosis after severe COVID-19 infection: A report of two cases. Ann Med Surg 2021;67:102468.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amsu.2021.102468

7. Piazza C, Filauro

M, Dikkers FG, et al. Long-term intubaÂtion and high

rate of tracheostomy in COVID-19 patients might determine an unprecedented

increase of airway stenoses: a call to action from

the European Laryngological Society. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol 2021;278:1-7.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s00405-020-06112-6

8. Miller R, Murgu

S. Evaluation and Classifications of Laryngotracheal

Stenosis. Rev Am Med Resp. 2014; 4:344-57.

9. Mathisen

D. Tracheal Resection and Reconstruction: How I Teach It. Ann Thorac Surg 2017;103:1043-8.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.athoracsur.2016.12.057

10. Wright CD, Li S, Geller AD,

et al. Postintubation Tracheal Stenosis: Management

and Results 1993 to 2017. Ann Thorac Surg

2019;108:1471-7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.athoracsur.2019.05.050

11.

Piazza C, Lancini D, Filauro

M, et al. Post-COVID-19 airway stenosis treated by tracheal

resection and anastoÂmosis: a bicentric experience. Acta Otorhinolaryngol Ital 2022;42:99-105. https://doi.org/10.14639/0392-100X-N1952

12.

Palacios JM, Bellido DA, Valdivia FB, et al. Tracheal stenoÂsis as a complication of prolonged intubation in

coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) patients: a Peruvian cohort. J Thorac Dis 2022;14:995-1008.

https://doi.org/10.21037/jtd-21-1721

13. Ramalingam

H, Sharma A, Pathak V, et al. Delayed Diagnosis of Postintubation Tracheal Stenosis due to the Coronavirus

Disease 2019 Pandemic: A Case ReÂport. A Pract 2020;14:e01269. https://doi.org/10.1213/XAA.0000000000001269

14.

Nauta A, Mitilian D, Hanna

A, et al. Long-term Results and Functional Outcomes After Surgical Repair of Benign LaÂryngotracheal

Stenosis. Ann

Thorac Surg 2021;111:1834- 41.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.athoracsur.2020.07.046