Autor : Osejo Betancourt, Miguel1, Saavedra, Alfredo2, Sánchez, Edgar A3,Milena Callejas, Ana4, DĂaz Santos, Germán5

1Specialist in Internal Medicine, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de Honduras, and Pulmonology, Universidad El Bosque, Bogotá, Colombia. 2Specialist in Internal Medicine and Pulmonology, National Cancer Institute of Bogotá, Colombia; Head Professor of Medicine, Universidad Nacional de Colombia. 3Specialist in Internal Medicine and Pulmonology, National Cancer Institute of Bogotá, Colombia, Associate Professor of Medicine, Universidad Nacional de Colombia. 4Specialist in Internal Medicine and Pulmonology, National Cancer Institute of Bogotá, Colombia. 5Specialist in Internal Medicine and Pulmonology, National Cancer Institute of Bogotá, Colombia.

https://doi.org/10.56538/ramr.NZAE4761

Correspondencia : Miguel Osejo Betancourt. E-mail: mosejob@unbosque.edu.co

ABSTRACT

The Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome is a rare autosomal dominant disease caused

by the pathogenic mutation of the folliculin gene,

which is mainly expressed in three organs that include the lung, the skin and

the kidney, and produces lung cysts, and renal and skin tumors. From the

respiratory point of view, it doesn’t have many symptoms, but cysts have high

risk of pneumothorax, so it is indispensable to carry out the correct

radiological semiology of the cysts for a timely diagnosis. The most important

tumors are the renal, because they include several types of renal carcinomas;

that is why they require strict follow-up and, in many cases, surgery. We

present two cases of patients with this syndrome: one confirmed by the genetic

mutation, and the other one by the histological confirmation of fibrofolliculoma, both major criteria for the diagnosis of

this disease. The early diagnosis of this entity is of fundamental importance,

according to what has been previously presented, so we conduct this review with

a broad discusÂsion about lung involvement, the radiological semiology of the

cysts, and diagnostic criteria.

Key wordsBirt-Hogg-Dube Syndrome; Pneumothorax; Carcinoma, Renal Cell;

Tomography

RESUMEN

El

sĂndrome de Birt-Hogg-DubĂ© es una rara enfermedad

autosĂłmica dominante cauÂsada por la mutaciĂłn patogĂ©nica del gen de la foliculina, que se expresa principalÂmente en tres Ăłrganos

que incluyen el pulmĂłn, la piel y el riñón, y produce quisÂtes pulmonares,

tumores renales y cutáneos. Desde el punto de vista respiratorio es poco

sintomática, pero los quistes presentan alto riesgo de neumotórax, por lo que

es imprescindible realizar una adecuada semiologĂa radiolĂłgica de los quistes

para un diagnóstico oportuno. Los tumores más importantes son los renales

porque incluyen varios tipos de carcinomas renales; debido a esto requieren

seguimiento estricto y, en muchos, casos cirugĂa. Presentamos dos casos de

pacientes con este sĂndrome; uno confirmado por la mutaciĂłn genĂ©tica y el otro,

por la confirmaciĂłn histolĂłgica de fibrofoliculoma,

ambos criterios mayores para el diagnĂłstico de esta enfermedad. Es fundamental

el diagnĂłstico temprano de esta entidad de acuerdo con lo expuesto anÂteriormente,

por lo que hacemos esta revisiĂłn con una amplia discusiĂłn sobre la afecÂtaciĂłn

pulmonar, la semiologĂa radiolĂłgica de los quistes y los criterios

diagnĂłsticos.

Palabras clave: SĂndrome de Birt-Hogg-DubĂ©, NeumotĂłrax, Carcinoma de cĂ©lulas renales, TomografĂa

Received: 12/21/2021

Accepted: 06/14/2022

INTRODUCCIĂ“N

The Birt-Hogg-Dubé (BHD) syndrome is a rare clinical-pathological entity

of autosomal dominant inheritance, described in 1977 by Birt

et al, chaÂracterized by skin neoplasia, generally

skin-colored soft papules on the face, neck and ears, with lung cysts and renal

neoplasia.1,

2

Up to now, more than 140

mutations in the gene related to this clinical entity have been described. The

gene is known as “FLCN”, and is located in the chromosome 17p11.2, which

encodes folliculin, a proÂtein expressed in multiple

tissues including the skin, type I pneumocytes, and

the distal nephron, whose exact function is unknown, but seems to act as tumor

suppressor by interacting with the pathway of the mTOR

(mechanistic target of rapamycin) protein, the tissue

growth factor beta and the DENN (diffeÂrentially expressed in normal and

neoplastic cells) protein.1-3 In this

article we report two cases of BHD.

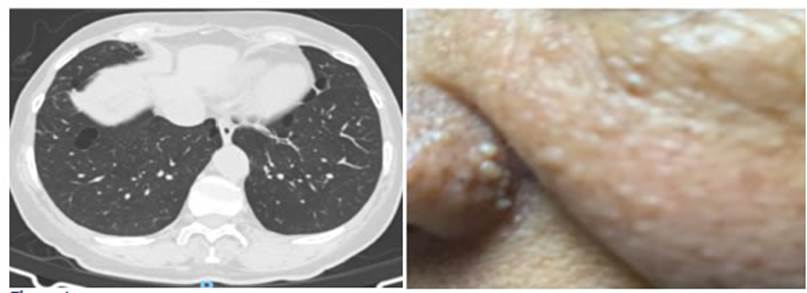

Case number 1

Female patient, 68 years old,

with history of hysÂterectomy due to cervical cancer 20 years ago. Thirteen

years later, she required a nephrectomy due to clear cell renal carcinoma;

subsequently, after two years, she showed yellowish pigmented papules on the

face, thorax and forearms, thus, she was assessed by dermatologic testing one

year later (Figure 1). The patient underwent biopsies of the papules on the

left nasal ala and anterior trunk, with histopathological findings compatible with angiofibromas, and then received urology and dermatologic

testing without new findings or symptoms. Given the presence of multiple

tumors, she was evaluated through genetic testing and underwent an axial chest

high-resolution comÂputed tomography (HRCT) that identified some lung nodules

of less than 1 cm and multiple, well-defined bilateral lung cysts of variable

size, with lens (lenticular) or round shape, some subpleural

and others, septated. So, a FLCN gene mutation study

was carried out, and found a mutation of the exon 11/18, variant c. 1285del,

pathogenic, thus confirming the diagnosis of the Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome (Figure 1). The patient was referred to the

Pulmonology Department for a complementary evaluation. She was in good general

condition, without respiratory difficulties or any other assoÂciated symptom.

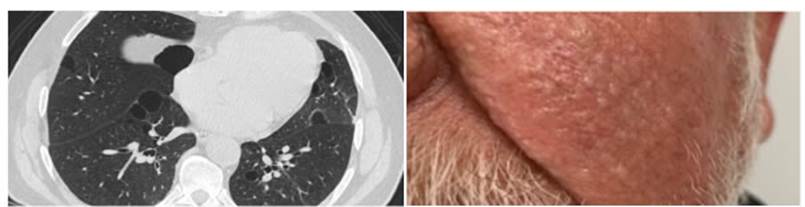

Case number 2

Male patient, 72 years old, light

smoker with a pack year index of 5 during 10 years, history of prostate cancer,

treated with radiation therapy and prostatectomy 9 years ago. Three years

later, the patient showed cough and dyspnea with great effort, of one month of

evolution, and was referred to the Pulmonology Department. The physical exam

showed multiple smooth surface papule lesions on the face, pedunculated

brownish hyÂperpigmented smooth surface papules on

the neck and external side of the right eye, and well-defined pigmented plaque,

greasy to the touch, on the chest (Figure 2). The rest of the physical exam was

normal, including lung auscultation. A spirometry was

performed with normal results, also a HRCT that showed two bullae and multiple

lung cysts of different sizes, some rounded and others with the form of a lens

(lenticular), which increased in number towards the bases, with the “alveolus

in the alveolus” pattern (cysts with internal septa) (Figure 2). Due to all

those findings, the patient was referred to the Dermatology Department for a

biopsy of the skin lesions. Biopsies taken from the lesions on the forehead,

the ear, and left cheek are compatible with tricofolliculoma.

Two years later, a renal ecography was performed,

which showed a complex renal cyst in the lower pole of the left kidney and

multiple bilateral simple cysts, and a tomographic study showed similar

findings. A new ecographic control carried out 2

years later identified a stable lesion when compared to the previous study. In

that case, the BHD diagnosis was confirmed, in accordance with clinical and histopathological findings of the skin biopsy. At present,

the Pulmonology Service performs the clinical follow-up; the patient doesn’t

show acute symptoms and has occasional coughing.

DISCUSSION

The BHD is a rare autosomal

dominant disorder caused by a mutation in chromosome 17 of the foÂlliculin gene; however, the physiopathological

meÂchanism involved is yet unknown.4 Some studies suggest that it causes hyperactivity of the mTor pathway and increases the production of growth factors

and aminoacids, which is considered the cause of

carcinomas and lung cysts.5

The most common genetic mutations

belong to c.1285dup/ c.1285dup + c.1285del (as the one identified in case 1),

c.1300G > C and c.250– 2A > G. Mutations in c.1285delC or c.1285dupC

account for 50% of BHD cases, whereas the other mutaÂtions are associated with

an increase in the risk of pneumothorax, present in up to 77% of the cases.4, 6

Skin lesions appear between the

third and fourth decade of life, and present with the classic triade of fibrofolliculoma, tricodiscomas and acrochordons in

90% of the cases. The lesions measure from 1 to 5 mm, and generally appear on

the nose, the nasolabial folds, the cheeks, the

forehead, the upper trunk, the ear lobe and the retroauricular

area.1, 7

80% of patients show lung cysts.2 The HRCT

shows well-defined, thin-walled cysts, usually multiple and bilateral, predominantly

basal (lower lobes), paramediastinal or subpleural, of variable size, but the most predominant

measure 1 cm. They can be rounded or lentiform, but

the morÂphology changes according to size: the bigger the cyst, the lower the

probability of it being rounded, and the higher the probability of it having

the “alveolus in the alveolus” pattern. These are cysts with internal septa.8

The real cause of the cysts is

unknown. The hypothesis about the stretching has been posed, suggesting there

are adhesion defects and that due to repeated hyperinflation, the alveolar

space expands2,

4 There isn’t gender predilection, they tend to appear from

the third decade of life. They can be complicated by pneumothorax in 20%-30% of

the cases, though it varies in familial cohorts, considered to have fifty times

higher risk of pneuÂmothorax than the general population, but it is much lower

compared to other entities such as lymphangioleiomyomatosis,

where the risk is a thousand times higher.1-4, 7, 9, 10

In patients with BHD, the

incidence of renal cancer increases seven times more than in persons not

affected by this syndrome, and generally tuÂmors appear in the fifth decade of

life. Variations have been described regarding the appearance of the tumors,

from 6.5% to 34%; they may be unilateral or bilateral, and the syndrome tends

to be more common in males. The most common are hybrid oncocytic

tumors and chromophobe carcinoma (50%-80%).1, 2, 4 Simple renal

cysts have also been reported, but since these are common in the general

population, no clear association has been shown.4

The diagnosis is usually delayed,

even for years, missed or wrong, since it can be confused with other causes of

spontaneous pneumothorax; and it is challenging, given the high genetic and

clinical variability: up to 25% of asymptomatic carriers, older than 20 years,

without skin lesions, or subÂgroups that show some mild fibrofolliculomas.12 The main

differential diagnosis is lymphangioÂleiomyomatosis

associated with tuberous sclerosis, due to similarities regarding the lung

cysts, and skin and renal tumors.4,

13

Patients with suspected BHD must

be evaluated with a HRCT for the analysis of lung cysts and pneumothorax, and

with abdominal CT or renal ecography at the time of

the diagnosis; also tomoÂgraphic follow-up must be carried out at least every

three to five years. We recommend the screening of first-degree relatives of

affected individuals aged 20 and upwards; and starting from 40 years, routine

screening for renal disease shall be carried out in search of tumors.1, 14

The clinical course of lung

evolution is not properly elucidated, and lung function tends to be preserved.3, 4 In

some cases, there is a decrease in the diffusing capacity for carbon monoxide,

particularly when there are multiple, big cysts; thus, when important changes

occur in them, we suggest taking lung function tests. Up to now, there isn’t

any well-known specific treatment, and no suitable response has been observed

with mTor inhibitors.3, 4

As part of the complementary

management, we recommend starting with the tobacco cessation program and

administering the pneumococcal and influenza vaccines.3, 4, 7, 9, 10, 13-15 A pneumothorax management program

shall be provided, incluÂding recommendations and warning signs. We recommend

that pleurodesis is performed after the first

pneumothorax episode, given its high frequency and recurrence; and, in cases of

recent pneumothorax, we suggest to the patient that he/ she shouldn’t take

non-pressurized flights or pracÂtice diving, since that may accelerate or

worsen the pneumothorax.3,

4, 7, 9, 10, 13-15

CONCLUSION

The Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome is a rare disease that requires high clinical

suspicion in order to begin its diagnostic approach. It should be susÂpected in

patients with skin and renal neoplasia and lung

cysts, particularly in cases with familial history of these conditions. The

study of this synÂdrome is part of the differential diagnosis of cystic lung

disease and corresponds to the third cause of that disease, which in comparison

with other etiologies, doesn’t have many symptoms from the respiratory point of

view, with little alteration of the pulmonary function. In turn, it is

essential to carry out the screening of first-degree relatives and follow-up of

reported lesions. The approach requires multidisciplinary management together

with dermatologists, urologists, nephrologists, geneticists and pulmonologists.

Conflict of interest

Authors have no conflict of

interest to declare.

BIBLIOGRAFĂŤA

1. Samayoa MA, MarĂa H, Garzaro DP. Birt

-Hogg-DubĂ© synÂdrome. Med Cutan Iber Lat Am. 2017; 45: 68-71.

2.

Fibla Alfara JJ, Molins

LĂłpez-RodĂł L, Hernández FerÂrández J, Guirao Montes A. NeumotĂłrax espontáneos de repeticiĂłn como

presentaciĂłn del sĂndrome de Birt-Hogg- DubĂ©. Arch Bronconeumol. 2018; 54: 396-7. https://doi.

org/10.1016/j.arbres.2017.11.017

3. Park S, Lee EJ. Diagnosis and treatment of cystic lung disease. Korean J Intern Med. 2017; 32: 229-38.

4. Daccord

C, Good JM, Morren MA, Bonny O, Hohl

D, Lazor R. Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome. Eur Resp

Rev. 2020; 29: 200042.

5.

Napolitano G, di Malta C, Esposito A, et al. A substrate-specific mTORC1 pathway underlies Birt-Hogg-DubĂ© synÂdrome. Nature. 2020; 585: 597-602. https://doi.org/10.1038/ s41586-020-2444-0

6. O’Carroll O, Cullen J, Fabre

A, et al. Phenotypic VariaÂtion of Birt-Hogg-Dube Syndrome Within a Single FamÂily.

CHEST. 2020; 158: 1790-1. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. chest.2020.04.065

7. Obaidat

B, Yazdani D, Wikenheiser-Brokamp

KA, Gupta N. Diffuse Cystic Lung Diseases. Respir Care.

2020; 65: 111. https://doi.org/10.4187/respcare.07117

8. Prat Matifoll JA, Andreu Soriano J, Prats Uribe A, Pallisa Núñez E, Persiva Morenza O, Varona Porres D. CaracterizaciĂłn en el TC de tĂłrax del sĂndrome de Birt- Hogg-DubĂ©: hallazgos para su diagnĂłstico diferencial.

Seram. 2018

9. Cooley J, Lee YCG, Gupta N.

Spontaneous pneumothorax in diffuse cystic lung diseases. Curr Opin

Pulm Med. 2017; 23: 323-33.

https://doi.org/10.1097/MCP.0000000000000391

10. Ferreira Francisco FA, Soares Souza A, Zanetti G, Marchiori E. Multiple cystic lung disease. Eur Resp Rev. 2015; 24: 552-64.

https://doi.org/10.1183/16000617.0046-2015

11. Sattler EC, Syunyaeva Z, Mansmann U, Steinlein OK. Genetic Risk Factors for Spontaneous Pneumothorax in Birt-Hogg-Dube Syndrome. CHEST. 2020;1 57: 1199-206.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chest.2019.12.019

12. Menko

FH, van Steensel MAM, Giraud S, Friis-Hansen

L, Richard S, Ungari S, et al. Birt-Hogg-Dube syndrome: diagnosis and management. Lancet

Oncol. 2009; 10: 1199- 206.

https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(09)70188-3

13. Gupta N, Seyama

K, McCormack FX. Pulmonary manifestaÂtions of Birt-Hogg-DubĂ© syndrome. Fam Cancer. 2013; 12: 387-96.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s10689-013-9660-9

14. Ennis S, Silverstone EJ,

Yates DH. Investigating cystic lung disease: a respiratory

detective approach. Breathe (Sheff). 2020; 16: 200041. https://doi.org/10.1183/20734735.0041-

2020

15. Godden D, Currie G, Denison

D, Farrell P, Ross J, SteÂphenson R, et al. British Thoracic Society guidelines

on respiratory aspects of fitness for diving. 2003; 58: 3-13.

https://doi.org/10.1136/thorax.58.1.3