Autor : Romina Fernández1,2, MartĂn SĂvori1,3

1 Department of Pneumophtisiology, University Center for Respiratory Medicine, Faculty of Medicine of the University of Buenos Aires, Hospital General de Agudos Dr. J M Ramos MejĂa, Autonomous City of Buenos Aires, Argentina. 2Head of Practical Assignments, UBA (University of Buenos Aires). Coordinator of the Pulmonology lecture. 3Certified teacher and Head of the University Center for Respiratory Medicine of the UBA. Course Director of Pulmonology.

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6628-0362

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5995-2856

Correspondencia : Romina Fernández. E-mail: fernandez.rn@gmail.com

ABSTRACT

Experience of a virtual course of

pneumonology for Medical students at the University of Buenos Aires during the

COVID-19 pandemic

The COVID-19 pandemic not only

affects people´s health: schools and universities around the world had to

forcibly adapt to a distance education modality. Knowing that the

epidemiological situation could continue for several months, the teachers of

our Unit, in charge of teaching Pneumonology, had to anticipate and devise a

contingency plan to ensure training continuity during 2020-21. The virtual

courses took place in four weeks. The classes were given in mp4 format and

virtual workshops. Once a week a virtual meeting was held to answer questions

related to the content. The students had to be divided into groups to solve

practical assignments and a final work with their defense at the end of the

course. In addition, they conducted a survey to evaluate the course. The final

exam was presential for the 2020 course and virtual for the 2021. All the

students who took the exam approved. The experience was enriching, different

and challengÂing. It allowed us to reflect and ask ourselves that the

traditional way of teaching can and should be complemented with the resources

that technology brings us. Although the total reopening of the University may

seem uncertain, this is the opportunity to betÂter plan the way out of the

crisis and promote internal reflection on the renewal of the teaching and

learning model.

Key words: COVID-19, Teaching, Pneumonology, University, Virtual learning

RESUMEN

La pandemia por COVID-19 no solo afecta la salud de las

personas: escuelas y uniÂversidades de todo el mundo debieron adaptarse de

forma forzosa a la modalidad de educación a distancia. Sabiendo que la situación

epidemiológica de la pandemia podía continuar por varios meses,

los docentes de nuestra Unidad, encargada de dictar la asignatura

Neumonología, debimos anticiparnos e idear un plan de contingencia para

asegurar la continuidad formativa durante el período 2020-21. Los cursos

virtuales se llevaron a cabo en cuatro semanas. Se dictaron clases en formato

mp4 y talleres virtuÂales. Una vez por semana se realizaba una reunión

virtual para responder preguntas relacionadas con el contenido. Los alumnos debieron

dividirse en grupos para resolver trabajos prácticos y un trabajo final

con su defensa al completar el curso. Además, reÂalizaron una encuesta

para evaluar el curso. El examen final oral fue presencial para el curso 2020 y

virtual para el de 2021, y aprobaron todos los alumnos que se presentaron. La

experiencia fue enriquecedora, diferente y desafiante. Nos permitió

reflexionar y plantearnos que la forma de enseñanza tradicional puede y

debe complementarse con los recursos que la tecnología nos acerca.

Aunque el momento de la reapertura total de la Universidad pueda parecer

incierto, esta es la oportunidad para planificar mejor la salida de la crisis y

promover la reflexión interna sobre la renovación del modelo de

enseñanza y aprendizaje.

Palabras

clave: COVID-19,

Enseñanza, Neumonología, Universidad, Educación virtual

Received: 09/15/2021

Accepted: 02/03/2022

The sanitary crisis has forced us to rapidly turn to virtual learning,

which implies joining efforts and reviewing the work done by each of our

institutions on open educational resources to make them available to the

different Ministries of Education and support the community of teachers in the

extremely important task of training their students on a long-distance basis.

Ulrike Wahl, Head of the Regional Office for Latin America of Siemmens

Stiftung1

INTRODUCTION

The SARS-CoV2 pandemic has

affected more than 362 million people and caused more than five and a half

million deaths around the world. In our country, more than eight million cases

have been confirmed, with more than one hundred and twenty thousand deaths2. But

the COVID-19 pandemic not only affects people’s health: schools and

universities all around the world shut their doors in 2020, affecting more than

one thousand five hundred million students from 191 countries3.

The Hospital General de Agudos

Dr. J M Ramos Mejía is associated with the University of Buenos Aires

(UBA) and teaches the subjects of the CliniÂcal Cycle of the Career of Medicine.

Our Unit is in charge of teaching Pulmonology during the month of May every

academic year since 1997, and is the University Center for Respiratory Medicine

of the UBA since 2020.

As a consequence of the extension

of the social, preventive and mandatory distancing4, in April 2020, the Rector of the

University decided that course subjects had to be taught virtually5.

Having projected that the epidemiological situation of the pandemic could

continue for several months, we adapted the syllabus and planned different

teachÂing strategies in order to meet the objectives of the educational

program. But even though we can anticipate all evident obstacles, teaching

medicine virtually is not completely possible: the most imÂportant thing this

career can teach its students is patient contact, and this can’t be transmitted

through a screen.

Amid difficulties, in May 2020

and 2021, coÂincident with the highest workload period at the hospital, the

first two Pulmonology virtual courses were carried out, intended for students

of the CaÂreer of Medicine of the UBA.

The purpose of this manuscript is

to tell the first experiences of both teachers and students with the

Pulmonology subject taught virtually in our Teaching Hospital Unit (THU) for

students of the Career of Medicine of the UBA during the 2020-21 period.

MATERIALS AND TEACHING METHOD USED

We have one certified teacher,

two assigned teachers and two senior teaching assistants for teaching the

subject. During April 2020, the syllabus and methodology of the subject were

redesigned. The Google Classroom platform and Zoom program were chosen for

teacher-student interaction. Between March and April 2021, some of the methods

that had been used the previous year were modified. Four days a week, two

classes were published. The classes had been previously recorded by teachers in

mp4 audio-visual format and supplemented with bibliography. A total of

twenty-two classes were taught in 2020 with the most important parts of the

syllabus. In 2021, a class in hemoptysis was added. Every day, students could

ask questions through the platÂform, and also graphics and bibliography were

added when necessary. In addition, student participation in class was

encouraged by asking questions through the platform to generate a debate and exchange

of opinions.

Once a week, a virtual workshop

on radiology was held for students to start recognizing lesions and patterns.

In 2020, there were two Power Point presentations includÂing the most frequent

patterns in radiology and chest tomography. In 2021, the workshop was

interactive: two Zoom meetings were scheduled, where teachers and stuÂdents

discussed radiological techniques and radiological and tomographic patterns.

Practical, face-to-face classes in the pulmonary lab and endoscopy were replaced

by tutorial videos. Classes in the pulmonary lab focused on spirometry

interpretation. In 2021, a virtual interactive workshop was held about

spirometries, where the students were able to analyze studies and relate them

to the diseases they had studied.

Once a week, a virtual meeting

was held to answer questions related to the topics that had been addressed. In

order to encourage team work, the students were divided in groups to resolve

clinical cases. Finally, each team carÂried out a work on a specific topic for

which they had to do some bibliographic research and present the work virtuÂally

at the end of the course. In 2020, the selected topics were: chronic cough,

viral pneumonia, inhalation therapy devices, hemoptysis and electronic

cigarettes. In 2021, the strategy changed: the students were given a clinical

case and were asked to organize a case conference and develop differential

diagnoses supported with bibliography, guided by a teacher assistant. The

clinical cases were about real patients: bilateral pneumonia in

immunocompromised patient, diffuse bronchiectasis, mediastinal mass, fungus

ball and pleural effusion.

Students were expected to submit

weekly practical asÂsignments, and then a final work at the end of the course

in order to be considered as regular. Each student was graded basing on the

level of individual class participation through the platform and the delivered

assignments, in accordance with resolution No. 106/2020 of the Board of

Directors of the Faculty of Medicine6.

At the end of each course, the students were asked to answer a survey that

allowed us to evaluate ourselves.

In 2020, the final exam was

postponed according to the resolutions of the Board of Directors of the Faculty

of Medicine7,

8, and students could be evaluated face-to-face in March

and April, 2021. In 2021, at the end of the course, students were evaluated

orally and virtually9.

RESULTS

Virtual courses were directed to

36 students in 2020 and 49 the following year. The proposed activities were

100% completed in both years: twenty-two classes in 2020 and twenty-three in

2021, two diagnostic imaging workshops, three weekly virtual meetings to answer

students’ inÂquiries, and one virtual workshop on spirometry in 2021. All the

groups submitted weekly practical assignments and also a final work presented

in a virtual meeting.

During the four weeks of each

course, interacÂtion between teachers and students was observed daily. In 2020,

students made 143 comments and questions through the platform; all of them were

answered with bibliographic support. In 2021, there were 180 questions. Most

consultations took place during weekly virtual meetings that lasted an average

of one hour and a half each.

Course evaluation

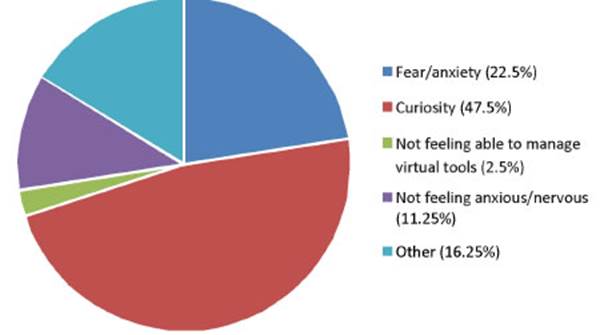

The final survey of the course

was answered by 100% of the students (36/36) in 2020 and by 90% (44/49) in

2021. Answers to virtual course expecÂtations were similar both in 2020 and

2021 (FigÂure 1). 16.5% of the students chose to create their own answers: “I

was scared I wouldn’t learn in the same way as in face-to-face classes”,

“Curiosity and excitement”, “Insecurity and doubts”, “I had already done two

virtual internships before withÂout such an active participation of the

doctors, so I thought the class was going to be quite fruitless”.

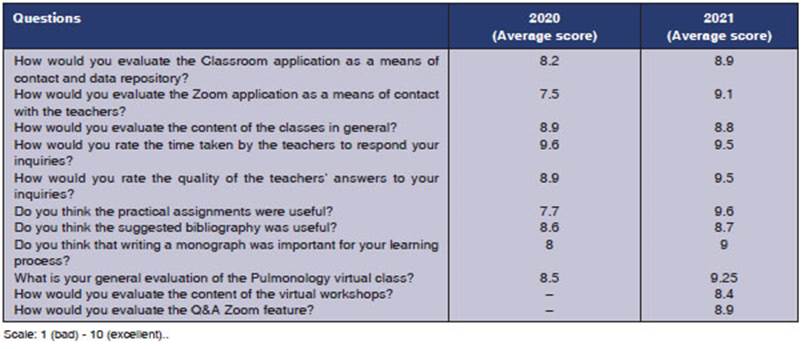

They were required to rate from 1

(bad) to 10 (excellent) the different aspects of the course, including the

selection of Classroom and Zoom applications; the content of the classes; the

usefulÂness of practical assignments and the final work; the bibliography

provided to them and the quality of teachers’ responses. Each year’s responses

were different, so we distinguished each one of them (Table 1).

Regarding the fulfillment of the

proposed sylÂlabus, 55.6% in 2020 versus 61.4% in 2021 said it was fulfilled

completely.

In the comment section of both

courses, we reÂceived very positive observations. Some criticisms of the first

course had to do with the number of practical assignments, which were useful

but too many, taking into account the duration of the course. They suggested

the imaging workshop should be more interactive. Regarding the apÂplication

used for weekly virtual meetings, they suggested other meetings without time

limit. However, they considered the meetings very useful to answer their

inquiries and suggested they were held more frequently. Many of these

criticisms were taken into consideration and were useful for the modifications

incorporated the following year.

Regularity and passing conditions

100% of the students obtained

regularity. In acÂcordance with resolutions in force during the 2020 course,

two dates were established for the face-to-face oral final examination (March

and April 2021): 28 out of 36 regular students (77.8%) took the exam (9 the

first date and 19 the second). All who attended the exam passed, with an

average grade of 9 points (range: 6-10).

In 2021, the oral final exam was

virtual. 30 out of 49 students took the exam (61%) distributed in three consecutive days. All of them passed with an average

grade of 9 points (range 8-10).

DISCUSSION

This was our experience with the

virtual PulmÂonology course, created a novo. Strong teacher-student

interaction was obtained with a high degree of satisfaction. Different virtual

platforms were used with online interaction (synchronous), questions were

answered during the day through the Classroom platform, and asynchronous activiÂties

were generated with clinical case resolution and bibliography provision. All

students obtained regularity, and a high percentage of students took the final

exam.

Suspension of

face-to-face classes in our country has impacted on almost two million students

and more than a hundred and forty thousand univerÂsity teachers10.

But closing the doors of the instiÂtutions of higher education not necessarily

means that academic activities have been suspended too. On the contrary, it

implies that universities must forcibly adapt to the modality of long-distance

education, and that teachers must do so without affecting quality and keeping

social inclusion11.

As teachers, this

experience has been enrichÂing, different and challenging in many aspects: on

one hand, an epidemiological context without precedent, high healthcare demand

and little time to prepare; on the other hand, using virtuality as a method of

communication between teachers and students for the first time, using

technology as the main teaching tool and, concurrently, maintainÂing good

quality. We had to prioritize objectives, redefine content and use virtual

modalities that could allow us to forge a bond with our students, not just a

mere exchange of information11.

All the virtual scheduled

activities could be completed in both courses. The evaluation on the part of

the students was encouraging and positive, since everyone obtained their

regular condition for the subject and 100% of the students who took the oral

final exam, (face-to-face in 2020 and virtual in 2021) passed it.

We believe the

improved 2021 course grades may be due to the modifications made, which

improved the teacher-student interaction by including synchronous virtual

workshops, and the encouragement to analyze clinical cases and organize case

conferences, a learning tool widely used among residents.

Regarding teachers’

training to be prepared to face a virtual course, during October 2020, the

Faculty of Medical Sciences together with the Center for Innovation in Technology

and Pedagogy (CITEP), dependent on the Academic Affairs Secretary, and the

Teaching Association of the University of Buenos Aires (ADUBA) taught the free

online course “Design of a Teaching Proposal within a Virtual Environment”. The

objective was to provide the tools necessary to allow for the optimization of

the online medical science campus and advice on the organization and

development of long-distance courses, virtual classroom administration and the

design and use of virtual evaluations and exams12.

Our first particuÂlar experience, a course taught in May 2020, was self-taught,

guided by intuition and the vocation for teaching. Since 2021, the Faculty of

Medical Sciences recommends its teachers to use Google Classroom as their main

platform, the same that was used by our THU13.

To restructure and

transform a purely face-to-face subject into a virtual course allowed us to

reflect on how traditional teaching has to be supplemented with the current

technology. “Supplemented”, not “substituted”. William Osler commented: “in the

teaching method that we can call “natural”, the student starts with the

patient, continues with the patient, and ends his/ her studies with the patient

(…)”14. We shouldn’t

lose sight of the fact that contact with the patient is the cornerstone of

teaching medicine: during the clinical cycle the students start to venture into

the doctor-patient relationship, learn to interrogate, examine and write

medical records. For this subject in particular, practical teaching (in the

operating room, pulmonary lab, inpatient ward, pulmonary rehabilitation gym,

chest imaging workshops) is impossible to reproduce fully in a virtual manner.

Regardless of the

pandemic, having a virtual class archive, bibliographic material and pulmoÂnary

clinical cases could be useful for certain situations where the student sees

the regularity of his/her career in danger (for example, surgeries with

prolonged postoperative time, immunocomÂpromised patients or any unforeseeable

circumÂstance).

During both courses,

we observed that not all students knew how to do bibliographic research, so

they were taught the basic management of the PubMed page. Another limitation we

found was the poor proficiency with the English language and, to a lesser

extent, the use of virtual platforms. Surely these situations will trigger in

many of them future questions whether they need further training to complete

the career and subsequently exercise the profession.

The epidemiological

situation gives us the opÂportunity to promote thinking about the possibility

of renewing the teaching and learning model and allow these experiences to be

integrated to the academic syllabus with the purpose of enriching and

reinforcing it. The virtual modality has been successfully developed with another

subject, highly accepted by students and teachers, who believe this methodology

can be added into the syllabus in a virtual/face-to-face format15.

It is extremely

important that us, as teachers, are trained in the design and management of virÂtual

environments so as to integrate them to the traditional academic model. It is

necessary that the University ensures good teaching quality in order to provide

feedback on what has been done up to now16.

But we should also

consider the emotional needs of the students who are taking the Clinical Cycle

of the career and can’t go to hospitals or have contact with patients and

teachers. Many of the students’ comments at the end of the course were about

the discouragement and lack of motivation generated by virtuality, partially

rectified by the methodolÂogy we use. We believe it is of crucial importance

that the moment we organize a subject that will be taught in a virtual manner

we put ourselves in the students’ shoes and use tools that help them achieve

their final objective as future professionals.

To conclude, the

virtual method of teaching Pulmonology allowed for a high degree of

teacher-student interaction through the use of different synchronous and

asynchronous virtual platforms. All the students obtained regularity and most

of them took the final exam.

Our hospital was the

first to be associated with the Faculty of Medicine of the UBA more than 140

years ago. It is the environment where patient care, research, and teaching

interact permanently. During those weeks, the teachers of the Unit had to keep

a balance between the increasing patient care demand due to the pandemic and

the virtual method of teaching the course, interacting with the students

through a new technology. This exÂceptional situation we had to face was and

still is a challenge that left us much learning and training for the future of

our career as teachers and doctors.

Acknowledgement

To the students of

our THU, our engine to keep improving and growing as teachers.

To Dr. Marcelo Amato,

teacher coordinator of the hosÂpital’s THU.

To Valeria

García, Secretary of the THU, the heart of the organization.

To the rest of our

teaching team: Dr. Daniel Pascansky, Ángeles Barth, Edgar

Velásquez, Mauro Zeolla, Juan JiméÂnez and Luciano Capelli.

Conflict of interest

Authors have no

conflict of interest to declare.

REFERENCES

1.

https://educacion.stem.siemens-stiftung.org/desafios-y-oportunidades-para-la-educacion-virtual-en-tiempos-de-cuarentena/

2. Ministry of Health

of Argentina. Coronavirus virtual ward. Available at:

https://www.argentina.gob.ar/salud/coronavirus-COVID-19/sala-situacion;

consulted in JanuÂary 2022.

3. Pedró F, Quinteiro JA, Ramos D y

col. COVID-19 y eduÂcación superior: de los efectos inmediatos al

día después. Instituto Internacional de la UNESCO para la

Educación Superior, mayo 2020. Available

at: https://www.iesalc.unesÂco.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/COVID-19-ES-130520.pdf,

consulted in October 2020.

4. Fernández A. Aislamiento social

preventivo y obligatorio. DECNU-2020-325-APN-PTE- Decreto Nº 297/2020. PrórÂroga. Available at:

https://servicios.infoleg.gob.ar/infoleginternet/anexos/335000339999/335974/norma.htm;

consulted in October 2020.

5. Barbieri A. Resolución sobre EXP.

Nº 13.300/2020 COÂVID-19 sobre cursada virtual. REREC-2020-423-E-UBA-REC.

April 3, 2020; consulted in October 2020.

6. Gelpi R. y Consejo Directivo.

Resolución 106/2020. CUDAP:

EXP-UBA: 0032167/2020. October 8, 2020; consulted in December 2020.

7. Barbieri A. Resolución sobre EX.

2020-01730887. REREC-

2020-1018-E-UBA-REC. October 7, 2020; consulted in December 2020.

8. Gelpi R. y Consejo Directivo. Resolución 029/2021. CUDAP: EXP-UBA: 4154/2021.

February 23, 2021; consulted in March 2021.

9. Negri C, Reyes Toso C. Circular Interna

N°31 de la SecreÂtaría de Asuntos Académicos de la Facultad de

Medicina de la Universidad de Buenos Aires del 09 de febrero de 2021; consulted

in February 2021.

10. Federación de Docentes de las

Universidades. El impacto de la virtualización en la educación

universitaria. Available at:

https://www.fedun.com/informe-sobre-el-impacto-de-las-cursadas-virtuales-en-la-educacion-universitaria;

consulted in September 2020.

11. Finkelstein C. La enseñanza en la universidad

en tiempos de pandemia. Centro de Innovación en Tecnología y

Pedagogía. Available at: http://citep.rec.uba.ar/covid-19-ens-sin-pres/;

consulted in October 2020.

12. Facultad de Ciencias Médicas de la Universidad

de Buenos Aires. Curso de online gratuito para docentes: “Diseño de la

propuesta de enseñanza en un entorno virtual”. Available at:

www.fmed.uba.ar; consulted in October 2020.

13. Facultad de Ciencias Médicas de la Universidad

de Buenos Aires. Si sos docente podés crear tu aula virtual. Available

at: www.fmed.uba.ar; home page, consulted in April 2021.

14. Buzzi A. Los aforismos de William Osler. Rev Asoc

Méd Argent. 2011;124: 3-5.

15. Spaletra P, Sigal AR, Gelpi RJ, Alves de Lima A.

ImplemenÂtación de una rotación virtual de cardiología en

tiempos de COVID-19. Medicina (Buenos Aires). 2020; 80: 587-8.

16. Vicentini I. La educación superior en tiempos

de COVID-19. Aportes de la Segunda Reunión del Diálogo Virtual

con Rectores de Universidades Líderes de América Latina. May 19-20, 2020. Available at: https://publications.iadb.

org/publications; consulted in October 2020. https://doi.org/10.18235/0002481