Autor : Busaniche MarÃa Agustina, SÃvori Martin

Pulmonology and Tuberculosis Unit. Hospital de Agudos J. M. Ramos MejÃa Autonomous City of Buenos Aires. Argentina

Correspondencia : mabusaniche@gmail.com

Abstract

In 2007, we carried out a descriptive study about the use of oxygen therapy during air travel (OAT) in our country (Medicina BA 2008; 68:433-36).

In this study we evaluate the current OAT service, both in domestic airlines (D) and international airlines (I). We conducted a telephone survey using the same methodology of the previous study. We communicated with 29 airlines (4 D and 25 I). We consulted them about the necessary requirements, costs and the possibility of obtaining information through their website, and then compared the results with the previous study. 25 airlines were evaluated (4 were discarded for lack of information, 16% of I airlines). Only one of them (4%) didn’t allow the use of OAT. Three airlines (12%) have an additional cost. The survey was resolved with only one phone call in most cases (2 calls for I) with an average duration of 5:53 minutes (± 1:31 min) for the D airlines and 8:42 minutes (± 3:45 min) for the I airlines. In order to provide the service, all the airlines request a previous medical report and 19 (79%) need a special form. 32% of the airlines provide the interface. 29% of the companies demand that the oxygen supply model should be part of the list of the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA). 80.5% has information available through the website. In conclusion, the information has been more easily provided with the website version. An improvement has been observed in services rendered by I flights, which have more demands in relation to the period of notice, controls and necessary requirements; also, a lower number of airlines imposes an additional cost for the service.

Key words: Oxygen therapy during air travel; Oxygen; Air travel; Argentina.

Introduction

Air traffic of domestic and international commercial flights has increased in recent times, causing a considerable rise in the number of patients with chronic pulmonary diseases who require oxygen therapy during air travel (OAT). According to the report published in 2013 by the International Air Transport Association (IATA), passenger demand would grow by 31% between 2012 and 2017. Calculating that in 2017 the total number of passengers would reach 3,910 million, it would be an increase of 930 million passengers compared to the 2,980 million passengers transported in 20121.

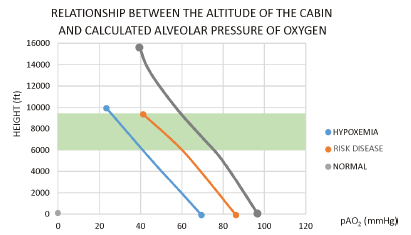

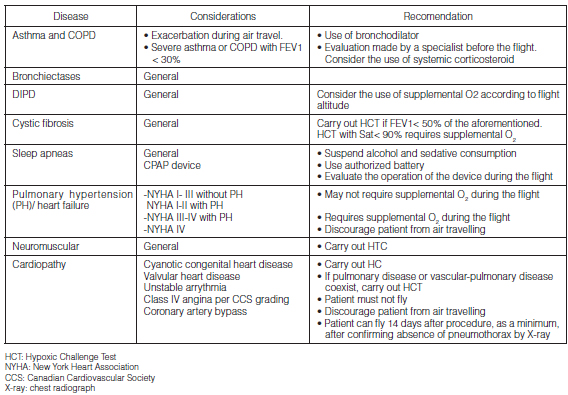

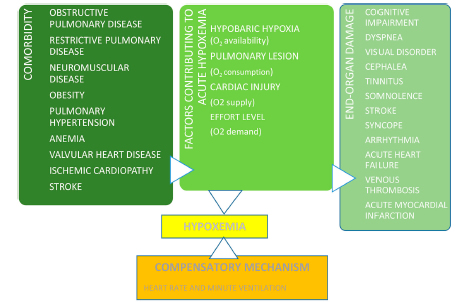

Most commercial flights, with a cruising altitude from 9,150 meters = 30,020 ft to 12,200 meters = 40,026 ft are incapable of maintaining sea level pressure inside the cabin, but establish it at an altitude of 2,438 meters above sea level (8,000 ft). At that altitude, the atmospheric partial pressure of oxygen is 14.4 kPa, which is the equivalent to a fraction of inspired oxygen of 0.151 (15.1%) at sea level2. Even though most passengers tolerate this reduction without any symptoms, those who suffer from chronic respiratory conditions may show an acute increase in their symptoms. (Graphic 1)3. Respiratory problems are the second most frequent emergency during commercial flights, after syncope or presyncope. So, patients with certain respiratory diseases that are going to travel by plane should be recommended to plan their trip far enough in advance4 (Graphic 2)3. The Argentine Consensus on Oxygen Therapy During Air Travel in Argentina

Long-Term Home Oxygen Therapy (LTHOT) states that patients with PaO2 > 70 mmHg at sea level probably won’t suffer damaging effects from hypoxemia during altitude exposure. Patients with moderate hypoxemia (PaO2 between 60-70 mmHg) will reach PaO2 values < 50 mmHg5 during the flight. So, they shall be tested for comorbidities (Graphic 3).3 There are predictive equations of hypoxemia during altitude exposure; there is even a hypoxemia simulation test to complete the evaluation6.

Regulations regarding air travel for this kind of patients vary enormously between the different airlines, without any standardization. The European Regulation (EC) No 1107/2006 about the rights of disabled persons and persons with reduced mobility during air travel has been adopted by the European Parliament and Council. It states that: “…given the fact that medical oxygen is one of the types of medical equipment specifically mentioned in Annex II of the Regulation, disabled persons shall be able to carry oxygen inside the cabin free of charge, provided the equipment meets the requirements relative to dangerous goods based on the regulations of the International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO) and the company is informed about it in advance. Airlines will decide if they provide oxygen directly to the passenger, but aren’t in any way obliged to do so. If they choose to do it, they are allowed to charge the passenger for the service. In cases where the passenger is charged for medical oxygen supply, the airline may decide whether they apply a discount or not. The price of this service shall be published as part of the applicable rules and restrictions. The airlines may demand that they should be informed in advance about the need to supply oxygen for a disabled person who wishes to use the airline’s oxygen supply service during a flight”7.

With regard to the current guidelines of the United States of America (EE.UU) the U.S. Department of Transportation (DOT) published a law in May 2008, which came into effect in 2009, called “Non- Discrimination on the Basis of Disability in Air Travel” establishing that all the airline companies taking off or landing in the EE.UU, regardless of the company’s flag, must allow the use of portable oxygen concentrators (POC) approved by the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA)8.

More recently, the European Federation of Allergy and Airways Diseases Patients’ Association updated this information in a document published in 2013. Mostly it specifies the importance of establishing a policy common to all airlines, including the need for oxygen supply during a flight to be free of charge9.

On the other hand, given the wave of international terrorist attacks and their relationship with air transportation, air navigation regulatory authorities have imposed strict regulations regarding the type of medical equipment to be carried on board10, 11.

Our group published in 2007 the different requirements, difficulties, systems and costs of a hypothetical passenger travelling from Buenos Aires both in an international and domestic flight using the same survey methodology of Stoller et al12. The purpose of this study is to determine the situation of oxygen therapy on board in Argentina both for domestic and international flights, using the same methodology as the one we used ten years ago.

Materials and Methods

To collect data, study researchers made phone calls between May 1-31, 2017 to all international (I) and domestic (D) airlines listed by Aeropuertos 2000 S.A. that were in operation in 2017 at the International Ezeiza Airport and the Domestic Airport of the City of Buenos Aires. Two airlines that covered both domestic and international routes (Aerolíneas Argentinas – Gol) were considered as two separate companies in every analyzed category: domestic (D) and international (I). Phone interviews were made using the same questions for all airline companies and the same methodology as the previous survey12-13. Calls were made from Monday to Friday, except for holidays, from 9 a.m. to 6 p.m. The person making the call identified himself/herself as a relative of the passenger requiring Long-Term Home Oxygen Therapy (LTHOT) as part of a treatment for a chronic pulmonary disease.

The questions were intended to find out if the company provided OAT, which medical documentation was necessary, number of days required for previous notice, interface availability, additional costs and website information. An electronic chronometer was used to check the time from the beginning until the end of the phone interview, determining the number of calls, in accordance with the methodology used in previously cited studies. Conventional statistical techniques were used. Continuous variables were expressed as a measure of central tendency in mean and as a measure of dispersion in standard deviation, since the measured variables had Gaussian distribution. Categorical variables were expressed in percentages and were compared using the Chi-Square Test. A value of p < 0.05 was considered to be significant.

Results

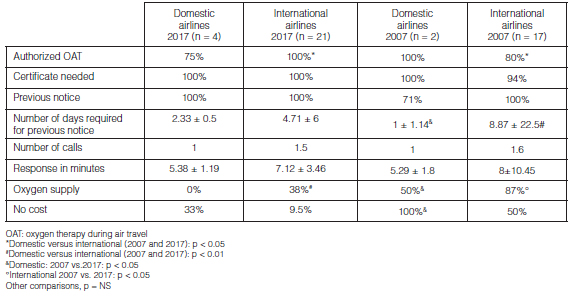

Four of the 29 commercial airlines that were consulted were national or domestic (D) (13.7%), and twenty-five were international (86.2%). Aerolíneas Argentinas and GOL were both. Four (13.7% of the total) were discarded due to lack of information (4 I, Convivasa-Cubana- S Africa – Air Canada). The analysis was made of the remaining airlines (n= 25). 100% of the I airlines and 75% of the D airlines who answered the survey questions allowed the OAT (except for ANDES, 25% D) (Table 1). 100% (n= 25) of the airlines required a medical certificate; and 79% (n= 19) required an additional form to be completed by the physician (web form). One company (Alitalia) requires an accompanying person who speaks English and/or Italian. 100% of the companies require previous notice. The number of days required for previous notice is 2.33 ± 0.5 days for D airlines and 4.71± 6 days for I airlines. The calls were made with one person of each company, except for two cases (Air Europa and Air France) where the phone call was made with two persons. Regarding the number of calls, the average was 1.5 calls: two with Air France and Air Europa and just 1 call with the rest of the companies. The average duration of the phone calls was 5.38 ±1.19 min for the D and 7.12 ± 3.46 min for the I (Table 1). With regard to the oxygen supply, 38% (n= 8) of the I airlines provides this service, whereas in 100% of the D airlines the patient must have his/her own oxygen supply (oxygen concentrators). 67% of D and 91% of I provide oxygen free of charge (Table 1). The additional cost of oxygen varies between 50 and 270 dollars (for Gol, total cost, for Boliviana per flight leg).

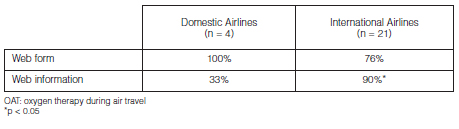

Regarding the website information of each airline: 80.5% of all the surveyed companies provide online information, and 79% have an OAT request form in the website. Such information is usually limited, so the passenger must make another phone call or send an email in order to obtain complete information. Difficulties may arise with the equipment model, since 28% of the airlines specify the model and only 38% provide it. The medical form for requesting oxygen therapy on board is available in all the domestic airlines and in most international airlines. Table 2 shows the differences in website information between domestic and international airlines, the international ones having more availability (p < 0.05).

Comparison with previous 2007 survey

In comparison with the study conducted in 2007, we analyzed a similar number of airlines. 100% of D airlines and 80% of I allowed OAT in 2007, whereas in this study the results were 75% D and 100% I, observing a decrease in this service only in D companies (Table 1). 100% of I and D require a medical report, and 79% also request a web form. In the previous study, 100% of D and 94% of I requested only the medical report. 100% of I and D request previous notice, compared to 71% for D and 100% for I in the first study, with a decrease in the number of days required for previous notice in domestic airlines (p < 0.05) and a strong increase in the number of days in international companies. There was an improvement in oxygen supply, both in domestic and international companies (p < 0.05), though it has

always been better in international companies. In terms of cost, there has been an increase in service rendering free of charge in D (p<0.05) and I airlines (Table 1).

Discussion

This descriptive study intended to evaluate all of the complications and requirements of a hypothetical passenger requiring OAT travelling from our country, and compare them with the study carried out 10 years ago. Lesser difficulties have been observed regarding the information provided by the airlines, with more requirements and controls. In domestic airlines there have been a decrease in the number of days required for previous notice and an improvement in trip authorization, oxygen supply and the fact that there is no additional cost for the patient. An improvement can be seen in access to international flights, with increased demands regarding time for previous notice and necessary requirements (certificates, equipment model and amount of batteries to be used during the flight), lesser number of airlines establishing additional costs and more information available to the passenger, including website information.

Though access to information has improved, the type of service is heterogeneous regarding quality and necessary requirements. Such heterogeneity can be seen in several aspects: oxygen therapy administration on board by the company, costs derived from oxygen administration and even variability regarding the use of any of the concentrators approved by the FAA and battery requirements14. In our study, an improvement can be seen at present in the reduction by half of the number of days for previous notice (p<0.05) and in the trip authorization, oxygen supply and the fact that there is no additional cost for the patient in domestic airlines, in comparison with the previous study (p<0.05) (Table 1)13. In the case of international companies, the number of days for previous notice has doubled, but there was an improvement in oxygen supply and better coverage free of charge, compared to the previous survey (p<0.05) (Table 1)13.

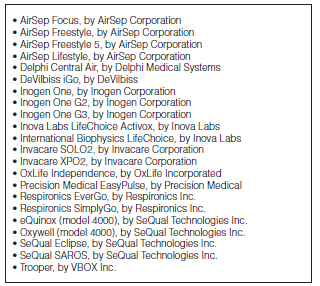

Companies that provide oxygen on board may set a limit on the number of passengers receiving that service during the flight. This situation is resolved when the patient travels with his/her own POC. At present, the FAA has standardized the POCs that can be used during air travel (Figure 1)15.

The airlines do not guarantee the availability of electrical connections and/or electrical supply inside the plane. For that reason, the passenger must carry the amount of batteries necessary to provide energy to his/her medical equipment for as long as he/she uses it. The number of batteries taken by the passenger for his/her POC shall be calculated by the patient’s physician, not by the airline, and shall be sufficient for the total duration of the flight plus an additional time in case there is any delay. The FAA distinguishes two types of lithium batteries: non-rechargeable lithium batteries and rechargeable batteries known as lithium ion. Lithium ion batteries not exceeding 100 watts/hour (used in mobile phones) can be transported as hand luggage and the amount is not restricted, as long as it is proportional to the number of devices carried by the patient and the duration of the flight. Regarding medium-power lithium ion batteries (>100 and ≤ 160 watts/hour), which are the ones used by the POCs, the IATA explicitly states that only two additional batteries can be carried on board14.

The airline companies reserve the right to deny transport of passengers whose equipment is not the one duly approved by the FAA or do not carry the sufficient amount of batteries or didn’t complete the formalities required by the airlines. The POCs and batteries may be carried as hand luggage and are not subject to restrictions regarding number of pieces or size, that is to say, they aren’t counted so the passenger may carry them as hand luggage with no additional cost1.

Website information of airline companies has links to “frequently asked questions” where oxygen transportation is mentioned. These questions are just guidelines for informative purposes. Mostly in our country complete information and web forms can be obtained through access to a web link or can be downloaded. Then, direct e-mail contact with the airline is required. All the international airlines and most domestic airlines (p<0.05) provide information through their websites. (Table 2).

There are different areas that need to be improved in the future, such as national standards that promote and regulate airline companies. Also, administration conditions, standardization of authorized equipment and regulation on board, as well as demands for patients who require OAT. On the other hand, future research should better define the potential risks of different health conditions and the selection of the adequate patient. Also, research must be done to know if in addition to FEV1 or arterial oxygen saturation there are other more reliable variables for detecting the adequate patient (dyspnea scale, exercise tests, other). Simpler and more easily available tests shall be developed other than the current hypoxic tests in order to predict whether a patient will be requiring OAT. Other more autonomous concentrators to be used in long flights and extended life batteries shall be redesigned.

To sum up, it will be convenient for scientific medical societies, especially in our country, and for the airline companies to establish standardized rules regarding OAT in order to resolve the frequent difficulties described in this study.

Conflicts of Interest: the authors declare there is no conflict of interest on this subject.

1. IATA publication No 67. [Feb 2014]. Access October 1, 2019 at: http://www.iata.org/pressroom/pr/Documents/Spanish-PR-2013-12-10-01.pdf

2. Global Strategy for the Diagnosis, Management, and Prevention of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease NHLBI/WHO. Workshop Report. www.goldcopd.com. Access on October 1, 2019.

3. Trevor T. Nicholson and Jacob I. Sznajder, Fitness to Fly in Patients with Lung Disease Ann Am Thorac Soc Vol 11, No 10, pp 1614-1622, Dec 2014

4. Peterson D, Martin- Gill C, Guyette F, Tobias A, McCarthy C, Harrington FS. Outcomes of medical emergencies on commercial airline flights. New Engl J Med 2013;368:2075–83.

5. Rhodius E, Caneva J, Sívori M. Consenso Argentino de Oxigenoterapia Crónica Domiciliaria. Medicina (Buenos Aires) 1998;58:85-94.

6. Gong H, Tashkin D, Lee E, Simmons M. Hypoxia-altitude simulation test: Evaluation of patients with chronic airway obstruction. Am Rev Respir Dis 1984;130:980-6.

7. Documento de trabajo de los servicios de la Comisión. Directrices interpretativas para la aplicación del Reglamento (CE) n° 1107/2006 del Parlamento Europeo y del Consejo, (2006) sobre los derechos de las personas con discapacidad o movilidad reducida en el trasporte aéreo. Bruselas 11.06.2012. Access on October 1, 2019 in: http://ec.europa.eu/transport/themes/passengers/air/doc/prm/2012-06-11-swd-2012-171 es.pdf

8. Department of Transportation. 14 CFR Part 382. NonDiscrimination on the basis of disability in Air Travel; Final Rules. Federal Register 2008: vol 73 N(93 pg 27614-27686. Access on October 1, 2019 at: http://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/FR-2008-05-13/pdf/08-1228.pdf

9. Enabling Air Travel with Oxygen in Europe. An EFA Booklet for Patients with Chronic Respiratory Disease] Access on October 1, 2019 at: http://www.efanet.org/wpcontent/uploads/2013/09/Enabling-Air-Travelwith-Oxygen-in-Europe-An-EFA-Booklet-for-Patients-with-Chronic-Respiratory-Disease.pdf

10. Mercancías peligrosas. Reglamentación vigente. Access on October 1, 2019 at: http://www.avianca.com/es/es/informacion-viaje/planea/equipaje/mercancias-peligrosas

11. REGLAMENTO (CE) No 820/2008 DE LA COMISIÓN de 8 de agosto de 2008 por el que se establecen medidas para la aplicación de las normas básicas comunes de seguridad aérea. Access on October 1, 2019 at: http://www.seguridadaerea.gob.es/media/4284467/regl_ce_820_2008.pdf

12. Stoller J, Hoisington E, Auger G. A comparative analysis of arraging in-flight oxygen aboard commercial air carriers. Chest 1999;115: 991-5.

13. Martinez Fraga A, Sivori M, Alonso M. Oxigenoterapia en vuelos nacionales e internacionales en Argentina. Medicina (Buenos Aires) 2008; 68: 433-6.

14. Cascante Rodrigo JA, Cascante R, Amaia A, Iridoy Z, Alfonso Imízcoz M. Marco legal vigente y aspectos prácticos de la oxigenoterapia durante los viajes en avión. Arch Bronconeumol 2015; 51:38–43.

15. FAA OKs three more oxygen concentrator models. [Feb 2014]. Access on October 1, 2019 at: http://www.faa.gov/news/updates/?newsid=75934